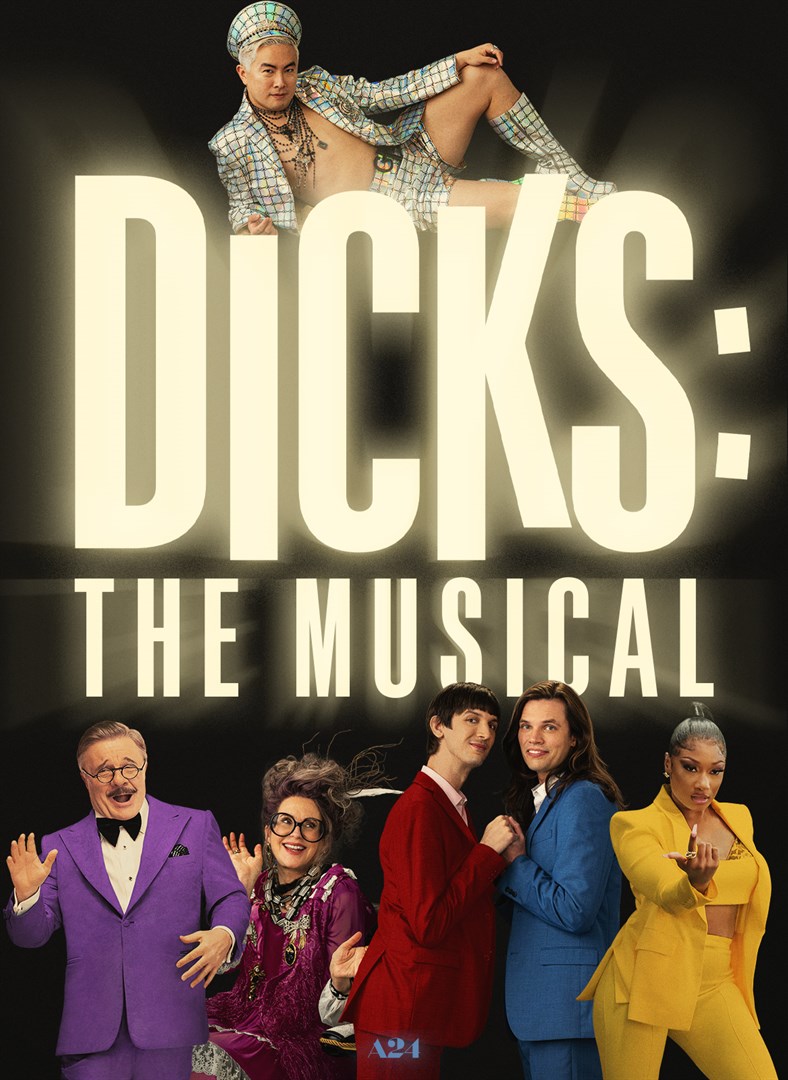

#11: Dicks: The Musical

Directed by Larry Charles, screenplay by Aaron Jackson and Josh Sharp.

Dicks: The Musical is available as a paid rental, and will be available to stream on Max.

Wonka, a film I broadly enjoyed, was middling and forgettable as a musical, and its terminal rehash of “Pure Imagination” was nothing less than a confession that the filmmakers were quite aware of that. Not so with Dicks: The Musical, which is one of the most memorable and horrifying musicals I’ve ever seen. This has to be why the film’s outstanding red-band trailer led with song – it knew it had a book of certified bangers on its hands. The film began as a two-man show off Broadway (called “Fucking Identical Twins”), and was expanded with new songs in its film adaptation featuring the talents of Megan Thee Stallion, Nathan Lane, and Megan Mullaly. The show’s original writer-performers (Josh Sharp and Aaron Jackson) reprise their roles as the [extremely obviously gay] alpha-hetero salesmen Craig and Trevor, who amp up the misogyny and horniness to a farcical pitch before turning to their main objective: discovering that they are long-lost brothers, and getting their parents (Lane and Mullaly) back together, despite everyone involved being an adult with a job and a place of their own, and despite Lane playing the only out gay man in the entire story – unless you count Bowen Yang as God. The production design from veteran art director Steven Wolff (an assortment of TV projects, plus Starship Troopers and Steel Magnolias?) is magnificent, with the film never missing an opportunity to turn a background poster into a horny joke. And that’s before you even get to the Sewer Boys, which – despite Trevor’s plea that his father explain them immediately – defy explanation both internally and upon review. They are, however, disgusting, hilarious, and a significant driving force behind the third act – and almost solely responsible for landing this film in the problematic 11th slot. Because Dicks is destined to become a cult classic, or so the Sewer Boys keep whispering inside my mind.

#10: Barbie

Directed by Greta Gerwig, written by Gerwig and Noah Baumbach.

Barbie is available to stream on Max.

Mattel, a toy company, isn’t going to shock me with its desire to sell more toys, any more than Nintendo trying to sell more games, or Hasbro smashing toy robots together. But movies are still a medium of stories and characters who will, at some point, have to explain to me why I should bother watching what amounts to a two-hour toy commercial, and the Barbie doll’s position as an iconic but dated piece of Americana doesn’t obviate that requirement. So you can imagine my delight when director Greta Gerwig (with a script co-written with frequent collaborator Noah Baumbach) decided to play with a broad and inclusive set of dolls, all singing and dancing a medley of existential dread on the border between Barbieland – a plastic, pastel fever dream (beautifully realized by veteran production designer Sarah Greenwood) where Barbie’s in charge and Ken is surplus to requirements – and the real world, where the Patriarchy is alive and well; we just hide it a bit better than we used to. It’s not much of a boast to say I’m less of a fragile little bran muffin than Ben Shapiro, whose vague fleshy blob turned instantly to windblown ash the moment the P-word was uttered in dialogue not once, but a baker’s dozen times. But if you’ll indulge me a problematic compliment, I was genuinely delighted to see that this toy commercial had some fucking balls. Because while my cynical side will assume that Mattel approved every image and sound that appears on this screen, and corporate feminism always exists with a degree of self-aware marketability, it’s hard for me to imagine that having a modern child (Ariana Greenblatt) tell Barbie to her crying face that she’s the dumb, fascist scion of a vapid and environmentally destructive consumer culture was their first advertising choice.

Written review (continued): “Barbie” (dir. Greta Gerwig) – Life in plastic

Podcast review: FilmWonk Podcast – Episode #206 – “Barbie” (dir. Greta Gerwig), “Oppenheimer” (dir. Christopher Nolan), “Asteroid City” (dir. Wes Anderson)

#9: The Royal Hotel

Directed by Kitty Green, screenplay by Green and Oscar Redding.

The Royal Hotel is available for paid rental on all VOD platforms, and will likely be streaming on Hulu later this year.

There’s nothing fun or glamorous about the latest subtle and brutal work of psychological terror and feminism from writer-director Kitty Green (The Assistant). This is not the only film on this list that engages in a credible way with the patriarchy, but it is the one that manages to do so without ever mentioning it in its script, instead presenting the reality of a pair of American expats (Julie Garner and Jessica Henwick). The pair navigates their way from partying in Sydney to running out of money and going to work as bartenders in a far-flung mining town in the Outback, where the misogyny, dick jokes, and possessiveness by the men who live and work there becomes the smothering ambiance of their daily lives almost immediately. And yet, the moment that most clearly announced the tone of this film took place back in Sydney, as Hanna (Garner) tries to buy a drink at a club and finds herself interrupted in turns by various men asking if she’s Swedish, if she’s French, disapproving of her choice of shitty Australian beer to drink, and finally a bartender (also a man) who instantly dismisses her request that he run her [declined] credit card a second time, turning her aside in favor of another dude ordering drinks. Now, her card was in fact maxed out, and the bartender ignoring her in favor of another customer was perhaps understandable. But at the end of this long train of minor masculine annoyances, it just played like the final twist of the knife. Don’t listen to her. Don’t indulge her. Given that she’s not going to fuck you at the moment. Just put her aside and seek your fortune elsewhere, until you’re off work and it’s time to hit on her again.

To the extent that this film had a message, it’s that walking through this world as a woman can be a constant, Kafkaesque trial. And it didn’t need even need to make it to the titular sausage fest flophouse in the middle of nowhere for these women to start to experience it. The Royal Hotel is just the metaphor that allows the audience to hold the patriarchy at a distance. And that’s what makes this film land in such a brutal and devastating fashion. It’s not that there aren’t any pleasant men in this film, or at least, moments of men behaving pleasantly, but all of them behave in ways that are informed by the incentives of the world they exist in – and those incentives encourage constant competition and hoarding of every resource, treating sexual access to women as the greatest resource of all, worth laying our fists into each other like beasts to secure. And whatever excesses they engage in while pursuing these objects – not people surely – are excusable as men acting like drunken, loutish men. And in a world of loud, disgusting, amoral, mendacious boors like Donald Trump and Boof the Rapist holding or pursuing every lever of power, the metaphor of this place lands even more harshly. Because The Royal Hotel is everywhere. And it’s good to be the king.

#8: The Holdovers

Directed by Alexander Payne, written by David Hemingson.

The Holdovers is available to stream on Peacock.

The Holdovers earned its place on this list almost entirely through its performances, as Paul Giamatti‘s multilayered cantankerous professor Paul Hunham is a fascinating enough ’70s character study even before you add in Da’Vine Joy Randolph as the school’s head cook Mary Lamb, a bereaved mother whose adult son was recently killed in the Vietnam War. The pair act as reluctant caregivers for student Angus Tully (debut actor Dominic Sessa), who is left behind over winter break at the prestigious Barton Academy in Massachusetts, where both adults work. Fundamentally, this is an amusing and heartwarming Christmas film about finding family in the least likely of places, and it’s to the film’s credit that it really makes its characters work for it. Truth be told, when I reached the third act, in which the trio goes on a bit of a field trip, I was expecting it to veer into shallow sentimentality. Instead, The Holdovers goes in some genuinely unexpected directions, but in a manner that is thoroughly explained and justified by the narrative and acting choices that preceded it. Yes, this film will make you smile and perhaps cry, but what makes it such a triumph is its presentation of flawed people embracing honest relationships with each other, and the joy they can find in that honesty. No matter how much they abhorred each other at the start.

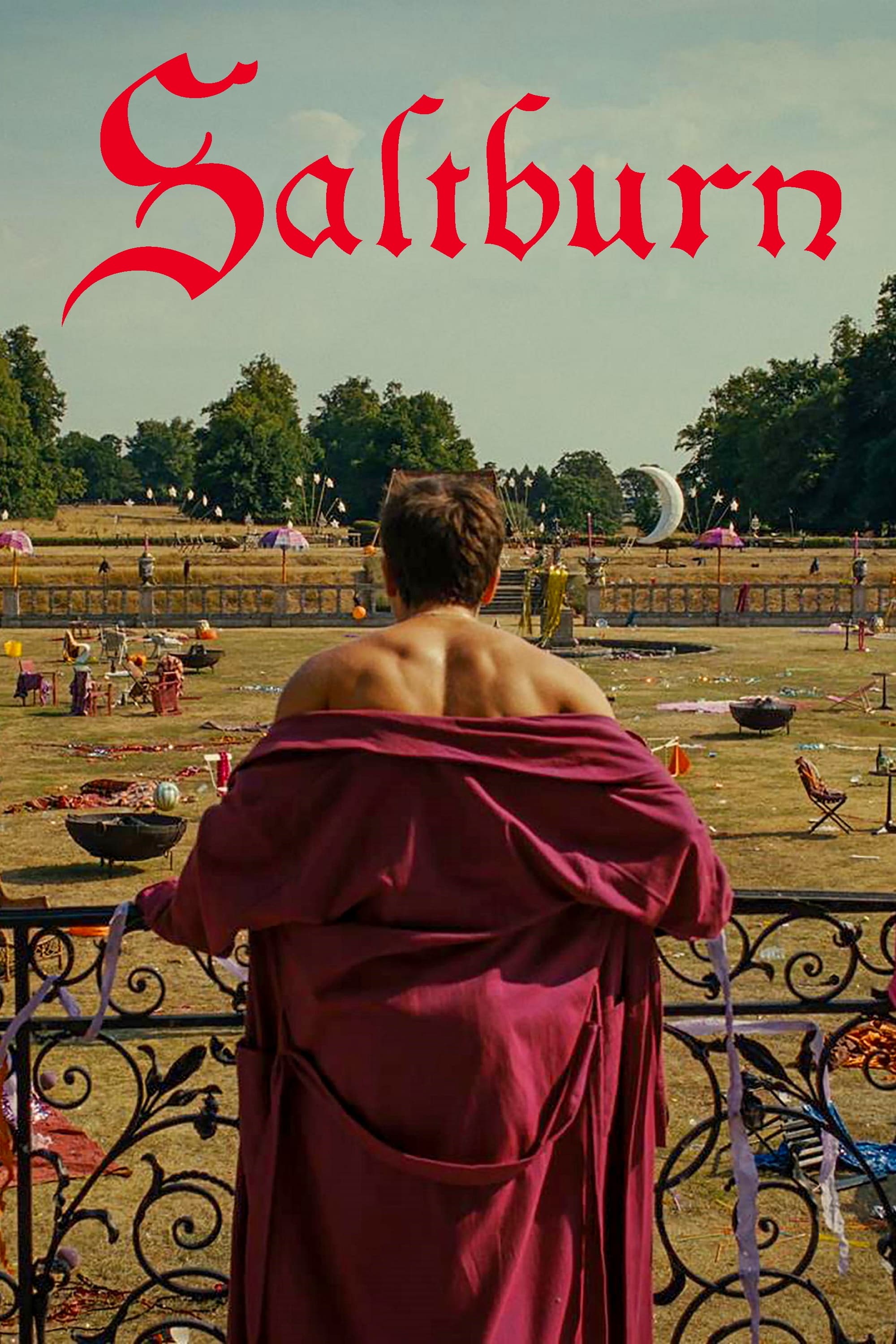

#7: Saltburn

Written and directed by Emerald Fennell.

Saltburn is available to stream on Prime Video.

Saltburn is under arrest, going directly to horny jail, along with everyone who made, watched, or enjoyed it. After two features from director Emerald Fennell, my oddest compliment is that she’s very good at making self-important melodrama. Promising Young Woman tapped a rich well of darkness and sincerity via the deep and longstanding rage of women living in the maw of patriarchy and rape culture – but it was fundamentally a tawdry, pulp revenge fantasy akin to Teeth – its most memorable scene had Britney’s “Toxic” playing, for fuck’s sake.

Saltburn feels tawdry for much of its runtime, but takes a while to explain what sort of revenge fantasy it wants to be, and rides that tension masterfully for its entire runtime. Which is fine, because I was captivated during its first act even before we arrived at the titular manor. Saltburn begins with Oxford scholarship student Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan) becoming friendly with – and then fixated upon – fellow student Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi), eventually becoming enmeshed in Felix’s wealthy, aristocratic family. As this Ripleyesque game is playing out, the feelings and motivations of its characters shift in ways that are perceptible, and yet demand a second viewing to see whether you properly understood each interaction as it was happening. Many of Oliver’s actions hover on the cusp between serving some larger, well-defined scheme and simply acting upon a desire to connect, dominate, and get off. And yet he seems like such a harmless, helpless thing at the film’s start – more flotsam than predator – and what a scheme it turns out to be nonetheless.

The story takes place in the mid-00s for no obvious reason – it’s not as if the relationship between wealthy landed gentry and their pauper friends has changed in any major way in the last 15 years. But each member of the family – especially Lady Elspeth (Rosamund Pike) and cousin Archie (Archie Madekwe) – is on the receiving end of very particular attention from Oliver, and watching them all throw verbal barbs at each other is quite an entertaining spectacle. I’m talking around what this adds up to because it is a satisfying mystery, although I suspect some will reach the end and find the answer unsatisfactory due to a lack of sympathy for any of these characters. And to that I say: Sympathy is often surplus to requirements. That the characters’ motivations are shifting and dubious makes them feel more real, not less – and that’s quite a statement when discussing a film which frequently borders on farce. It also ends with a dance that must be seen to be believed.

#6: Rye Lane

Directed by Raine Allen-Miller, written by Nathan Bryon and Tom Melia

Rye Lane is available to stream on Hulu.

The romantic comedy has been on life support for years, relegated to the sort of artless posturing that gets vomited en masse at Christmastime, selling romance on the basis of extinct, apolitical small-town and holiday vibes entirely external to the individuals involved. At best, the genre has transcended this formula by either embracing it with a bit of self-awareness (as in Somebody I Used to Know) or raising the stakes with a sci-fi or fantasy genre pairing (as in Palm Springs). So you can imagine my surprise and delight to see this debut feature from director Raine Allen-Miller, a talent I will be keeping an eye on in years to come. This Gen-Z romance was written from a script that was originally titled Vibes & Stuff, and this is a decent summation of the romance that erupts in an arts district between a pair of south Londoners, Yas and Dom (Vivian Oparah and David Jonsson), who have an awkward meet-cute in the gender-neutral loo where Dom is crying in a stall about his recent horrible breakup (he calls it The Breakup – that’s how you know it’s recent). They’re both at a weird art exhibition, featuring an artist and mutual friend, Nathan, played by Simon Manyonda, who steals the handful of scenes he’s in, beginning with Nathan warning his tearful friend that if he can’t keep it together, and he’ll have to “sling a sign on [him] and call it performance art”. But Yas and Dom just keep right on vibin, looking at the weird art (with Dom succumbing to peer pressure to buy some) and then wandering out together in the same direction, through Rye Lane Market.

Here in Seattle, we have Pike Place and other such markets (and if I’m being honest, our unwillingness to banish out-of-place cars somewhat limits its appeal beyond tourists), but it’s fair to say that every slightly interesting city has a place like this, and it’s always a prime location for people-watching, grabbing a quick or weird bite, and bonding over a shared feeling of being a part of the city you’re in. For a rom-com or a real date, its built-in production design provides a stellar backdrop for an impromptu wander to bond with a stranger. Yes, I’m showing my urban bias here a bit, but I find this romance of odd hipster happenstance to be far more credible on its face than the city magazine editor returning to Frost Gulch, Wisconsin to bond with a suspiciously well-groomed lumberjack who is silent about where he was on January 6th. A good deal of this is owed to Oparah and Jonsson’s stellar chemistry and charm, but it also relies on the film’s sense of style and self-awareness when it comes to the artificiality of a first meeting like this. Yes, they’re doing a bit of a Before Sunrise here, wandering the city and talking about what matters to them both, but they’re also putting on a bit of a show for each other and the others they interact with, doing an impression (or perhaps an audition?) of a relationship they don’t yet have with each other. And what is a first date, if not that? It’s when these vibes and gestures – hilarious in their own right – give way to the unvarnished truth and emotional vulnerability that it really feels as if these two are connecting, and that journey really is a pleasure to behold. It didn’t need Colin Firth to cameo as a burrito truck chef wearing a “Love Guac’tually” t-shirt, but it was nice to see the old guard pop in to give a stamp of approval that this film had already earned on its own. Rye Lane is an hilarious and artful romance. One for the canon.

#5: Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves

Directed by Jonathan Goldstein and John Francis Daley, screenplay by Goldstein, Daley, and Michael Gilio, story by Gilio and Chris McKay.

Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves is available to stream on Paramount+.

[The] requirement to balance coherent storytelling with freewheeling anarchy might explain why a tabletop RPG like Dungeons & Dragons has some unique adaptation challenges compared to video games (which also have a fairly spotty cinematic record). If you want to adapt a video game, your choices exist on a spectrum between “make a version of the game as played by the best player ever” and “just slap the name onto an generic adventure tale that vaguely resembles it”. Previous attempts to adapt D&D have largely opted for the second method – but this feels like the first attempt to capture the loose, jokey, improvisational chaos that is fundamental to the appeal of the game. You’re telling a story, sure, and that story ultimately has to make some kind of sense. But you’re also making choices ranging from the rational to the ridiculous, and rolling the dice as to the outcomes of those choices. A skilled DM will attempt to balance the madcap randomness of gameplay with the fun and coherence of the story (usually by selectively breaking rules as needed) – and that seems to be the difficult path that these filmmakers chose to tread – or at least convincingly imitate – with the script of Honor Among Thieves. And to my unrelenting delight, it worked.

Full review (continued): “Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves” (dir. John Francis Daley, Jonathan M. Goldstein) – Make your saving throw and still get charmed

[…]

If all the best parts of a campaign occurred in a single rowdy, Mountain Dew-soaked night, without any table drama or rules-lawyering or spell slot fuckery – with good ideas rewarded by creative counterattacks from the DM, without every choice succeeding, but each one resulting in the sort of improvised flailing that molds it into an even more insane plan with each moment – it might look something like this movie. And I’d be talking my friends’ ears off about it the next day until they begged me to stop.

#4: Linoleum

Written and directed by Colin West

Linoleum is available to stream on Hulu.

Linoleum is a surreal dramedy about Cameron Edwin (Jim Gaffigan), the host of a failing children’s TV science show, à la Bill Nye, and his wife, an aerospace museum curator (Rhea Seehorn, the absolute rockstar from Better Call Saul), who are having troubles and headed for divorce, when a satellite crashes in their backyard, and the TV host decides he wants to try and build a rocket out of it.

The other plotline involves their daughter Nora (Katelyn Nacon) who strikes up what might be a romance or a platonic friendship with a new boy in town, Marc (Gabriel Rush). Nora and Marc’s connection is ambiguous for the usual reasons (they’re confused teenagers), but also because as a prior condition, she makes it clear she’s not flirting with him, because she likes girls. But she also finds him interesting and wants to be pals, and the feeling seems to be mutual. Marc’s father is Kent Armstrong, a hardened ex-military man who is about to take over network hosting duties of Edwin’s science show. It’s hard to imagine this man commanding the attention of children in quite the same way as Edwin, and yet…he is also played by Gaffigan? Gaffigan-as-Armstrong is a deathly serious exercise in self-parody, transforming so thoroughly in appearance and manner that I found myself unsure at times whether I really was looking at the same actor. It’s genuinely bizarre as a starting point, and the film only gets stranger from there, despite retaining its earnest streak and heartfelt performances that roped me into the story initially.

The vibe of Linoleum, as well as several of its visual, musical, and thematic tricks, are cribbed directly and unapologetically from Richard Kelly‘s 2001 film Donnie Darko, but it is also very much its own thing. It ends up being a fascinating elegy on childhood hopes and dreams, love, identity, and a lot more – and that is about the limit of what I may say here, because as with Donnie Darko, the outstanding ending of this film ties all of the surreal elements together in a manner that is comprehensible, but not explained perfectly in the text. You’ll walk away feeling as if the journey made sense, but it will decline to answer every question.

#3: Poor Things

Directed by Yorgos Lanthimos, written by Tony McNamara

Poor Things is in theaters now, and will stream on Hulu at a date yet to be announced.

Lanthimos makes his third appearance in the Glennies and McNamara his second, with the writer-director pair having previously written The Favourite (also starring Emma Stone), which was my favourite film of 2018. McNamara went on to apply his thoroughly debauched and loosely historical eye to The Great on Hulu, which I’ve adored in the intervening years, so naturally I came into this film fully prepared to see what twisted, sexy, violent, and utterly human spectacle he would bring to bear on the sci-fi genre. And yet, I was unprepared for just how much the film would rely upon a single, transformative performance from Stone, who also executive produced the film.

Stone plays…Frankenstein, essentially. A creative amalgamation of a mad scientist and twisted parental figure played by Willem Dafoe. Yes, the first sentence was a pedantry test, and you passed, dear reader. Stone is Bella Baxter, an assemblage of recycled parts made manifest by the dream of a madman named Godwin (“God” for short), who watches her toddle about like a child before bringing in medical student Max McCandless (Ramy Youssef) to take notes on her cognitive and linguistic development. The steampunk menagerie in which God operates is utterly depraved to a degree that seems familiar within Lanthimos’ oeuvre (feels like a satellite operation to The Lobster), but which serves a clear narrative purpose. This is a man who sews animals together for scientific fun. He has a half-goose, half-dog. A half-pig, half-chicken. And they all wander around the yard perfectly healthy to show off his crimes against nature, and offer a preemptive explanation for the inevitable question: Why is Bella Baxter? Because when we learn Bella’s origins in the first 30 minutes of the film, there’s no reason why he had to bring her to life in this particular way except that God is a mad scientist, and wanted to see if he could. And yet, in his own way, he was following his own code of ethics in doing so, not violating the will or decisions of his unwitting parts-supplier.

What follows is a Bildungsroman – a chronicle of Bella’s growth, engagement with the world, and gradual intellectual and philosophical awakening as she embarks on a series of romantic and depraved adventures, initially with the rakish Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo), who is as basic and hilarious as he is despicable and unimportant (with an absolute hoot of a performance by Ruffalo). Duncan absconds on a romantic adventure with Bella…in order to fuck and then discard her, obviously, and Bella makes it clear that she knows exactly what use they have in mind for each other. And yet, for all the worldliness that gradually coalesces from Bella’s self-styled “questing nature”, Stone’s performance never fully leaves behind the verbal and physical tics that the character had at her start, nor the innocence with which she approaches every question about why the world is how it is. And it is Bella’s guileless exploration that makes Poor Things so utterly fascinating, as she meets other characters who could have existed as mere mouthpieces for a particular worldview, and yet feel fully formed and appealing as objects of exploration. She finds the most interesting people in the room and becomes one of them in turn, schmoozing with the likes of consummate cynic Harry Astley (Jerrod Carmichael) and brothel madam Swiney (Kathryn Hunter), each of whom acquits themselves well in the handful of moments they have in this film.

Bella finds herself, her friends, and her purpose, and what a wondrous journey of self-discovery and self-possession it turns out to be, with the world itself rendered in a fantastical blend of miniatures and CGI reminiscent of Wes Anderson and yet justified as an expression of how Bella sees the world: full of wonder, despite and because of its myriad horrors and contradictions. Poor Things is a delight, despite its frequent attempts not to be.

#2: American Fiction

Written for the screen and directed by Cord Jefferson, based on the book by Percival Everett.

American Fiction is in theaters, and will be available to stream on Prime Video, on a date yet to be announced.

American Fiction is sincere, hilarious, and a great deal more than the sum of its elevator pitch: that frustrated fiction writer and professor Thelonious “Monk” Ellison (Jeffrey Wright) would adopt an authorial minstrel persona in the form of fictitious fugitive “Stagg R. Leigh” in order to write a pandering pastiche of Black trauma porn, only to see it embraced by the literary establishment and the white world writ large. And the film’s greatest trick is to treat this pitch…as an afterthought to the establishment of Ellison himself – and his family, history, and relationships – as the furiously beating heart of this film.

Full review (continued): “American Fiction” (dir. Cord Jefferson) – A skewering of authenticity

[…]

Monk doesn’t hide his contempt for the publishing world…at one point demanding on a conference call to the marketing department that his new book be retitled from My Pafology to simply…Fuck. Which, of course, they agree to do, and it only makes the book more buzzworthy. It hardly matters whether an artless exercise in self-parody actually gets read by anyone, as long as it makes for an interesting cover and conversation piece. Monk’s literary agent Arthur (John Ortiz) concludes a reading of a racist review of his last book, in which the critic essentially tells Monk to stay in his lane (wondering what the book’s subject matter “has to do with his experience as a Black man”) by commenting that white people think they want the truth, but what they really want is absolution.

[…]

As a critic, American Fiction was a reminder to stay humble. And as a reader of fiction, American Fiction was a reminder that nobody knows anyone else’s life. And sometimes, the richness and texture of that life can be pleasant to immerse yourself in whether or not you can turn it into a grand observation about your own.

#1: Killers of the Flower Moon

Directed by Martin Scorsese, screenplay written by Scorsese and Eric Roth, based on the book by David Grann.

Killers of the Flower Moon is available to stream on Apple TV+ on January 12.

It’s rare that I give a film 10/10 – the last such recipient was American Factory (my #2 of 2019), and Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of the non-fiction book Killers of the Flower Moon, while not a documentary, received this nod for a similar reason: it answered a question I didn’t even know to ask, and did so in a manner which left me thunderstruck, unwilling to change a single thing about it. The United States of America is exceptionally good at making tokenistic nods to the sins of its past, but is deliberately less thorough when it comes to connecting that past to present dysfunction and economic inequality, content to maintain a narrative that Americans have always succeeded through skill and hard work, and anyone who is poor and downtrodden probably deserves to be in some way at this point. After all, all those bad things we did to them are in the past, and everyone affected by them is long dead, right? Right?

We’re all quite familiar with this attitude as applied to slavery, but perhaps a bit less so with the myriad mistreatments and indignities that the surviving members of the Indigenous peoples of this continent have had to suffer. After the wars, genocides, forced resettlements, and invasive diseases decimated their pre-Columbian civilizations, shunting tribes onto reservations of the most useless and remote land that the white government could deign to provide was also a fine excuse to ignore them in perpetuity. Imagine their surprise when some of that land turned out to be bubblin’ crude? The resulting oil wealth flowing into the Osage Nation in Oklahoma also brought a flood of white supremacy, ensuring that as much of that money would be clawed back as possible. Because if there’s one thing this country cannot stomach, it’s the wrong people getting rich.

It’s this hands-off attitude toward the uncomfortable and ceaseless tide of history – reinforced by all levels of government and politics for over a century (and currently being aggressively pushed by the know-nothing, iconoclastic resurgence of the white nationalist GOP) – that has caused acts of terrorism like the Tulsa race massacre (which gets an explicit nod in this film) to fail to be taught in schools and not become widely known until the 2010s. The institutionalized abuse of guardianship and a campaign of organized crime and theft against the oil wealth of the Osage Nation in the 1920s is a similar tale, in that I had truthfully never heard of it until this film was made. And that’s the rub, isn’t it? As with the fictitious white world of American Fiction above, I find myself praising this film for its fearless truth-telling, grappling with America’s original sins, even as I know that I’m seeing this story from the perspective of the white people who decided to tell a story that the Osage Nation itself was telling continuously while it was happening, and ever since. The original trite observation about history is that it is written by the victors. And that is true even for the subset of those victors who fruitlessly seek absolution for the life they now enjoy, built upon the shoulders of giants – and trod upon the victims of the same.

Flower Moon‘s powerhouse set of performances include another career-best from Robert De Niro as pimping gangster and gleeful white supremacist William King Hale, and another from Leonardo DiCaprio as Ernest Burkhart – a riveting, classic dumb guy, a Great War veteran with nasty teeth and zero prospects until his uncle decides to set him up as a potential murderous husband to Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone), an Osage woman whom they fully intend to murder along with her entire family in order to ensure that her oil rights end up in their white hands. On our podcast, I commented that the film’s sprawling ensemble cast and demystifying of a historical turning point reminded me favorably of Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln – but ultimately, its best reminder of that film came with how much preexisting baggage of American history education that I bring to it. Because as a wholly unfamiliar story, the events of this film (of a rein of terror and murder that lasted for years) would already be devastating. But with everything I know of the rise of the global oil industry and its role in building American wealth during the 20th century, it provokes a bit of a knowing nod. “Ah, that makes sense.” While I have nothing but praise for Gladstone’s performance as well as the rich tapestry of Osage life, dress, culture, etc., that is presented in this film (and which the real-life Osage Nation apparently had quite a bit of involvement with), it is hard to come away feeling as if I really know these people or understand their perspective on these events, because we’re essentially just watching them be victimized as part of a true crime drama in which all of the heroes and villains are white, and the victims – however richly they are rendered, are mere props and crying icons.

I truly don’t know how to square this circle, except to say that Killers of the Flower Moon seems well aware of its limitations as a story told by and for white people. And my only hope in lauding the film so thoroughly is that it doesn’t end the conversation about it, because the various peoples at the heart of this film have a lot more to say to anyone who will listen.

Check out our podcast review:

FilmWonk Podcast – Episode #207 – “Killers of the Flower Moon” (dir. Martin Scorsese)

Honorable Mentions:

- Joy Ride (directed by Adele Lim, written by Cherry Chevapravatdumrong and Teresa Hsiao)

- Dream Scenario (written and directed by Kristoffer Borgli)

- Oppenheimer (written and directed by Christopher Nolan, based on the book by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin)

- Nimona (directed by Nick Bruno and Troy Quane, screenplay by Robert L. Baird and Lloyd Taylor, based on the graphic novel by ND Stevenson)

- How to Blow Up a Pipeline (directed by Daniel Goldhaber, written by Goldhaber, Ariela Barer, Jordan Sjol, based on the book by Andreas Malm)

- Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (directed by Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, and Justin K. Thompson, written by Phil Lord, Christopher Miller, and Dave Callaham)

- Asteroid City (written and directed by Wes Anderson)

- LOLA (directed by Andrew Legge, written by Legge and Angeli Macfarlane)

- M3GAN (directed by Gerald Johnstone, screenplay by Akela Cooper, story by Cooper and James Wan)

- Beau is Afraid (written and directed by Ari Aster)

- May December (directed by Todd Haynes, screenplay by Samy Burch, story by Burch and Alex Mechanik)