#11: Borat Subsequent Moviefilm

Directed by Jason Woliner, written by Sacha Baron Cohen and literally seven other people.

As ever, the #11 slot goes to a film that I enjoyed but have serious reservations about. I daresay Lindsay Ellis spelled these out better than I can: the character Borat works better in 2020 because America is uglier and more disturbing than it was when the first film was released. That’s a hard statement to defend as an American, given that we’ve been continuously at war since before that time, and the most popular TV shows in 2006 were all about explaining to the American public that Torture Works, Actually (it doesn’t). But what’s different now is that America doesn’t even bother to hide its ugliness – of the racist, sexist, anti-Semitic, homophobic, or transphobic variety, anymore. Our Republican politicians – useless, preening, bloodthirsty, plutocratic, unpatriotic, social-media-influencer scum that they are – openly suborn violence and try to overturn elections because they failed on this occasion to suppress as many legal votes as they would have liked. Each deplorable faction finds its bigoted beliefs emboldened as they are repeated in front of the press, the public, and in the halls of power. So when comedian Sacha Baron Cohen dons his Borat garb and tries to get people to agree with the horrible things he’s saying, even working at a disadvantage of a much more recognizable public persona, he has a significant advantage insofar as the people he spoke to were far more willing to engage with him, as if they were just waiting for someone who wanted to smile and agree with them. This is also the first piece of popular culture that engaged in any serious way with the COVID-19 pandemic, and it even touched upon my home in the Pacific Northwest by showing up to an event headlined by 2020 Republican gubernatorial nominee Loren Culp, a notably pro-virus dingbat and former police chief of a one-man, one-dog department in a one-horse town that fired him as soon as the election was over. I wouldn’t normally be punching down at him, but I’m doing so here because he spent the intervening months in an infuriating and sad impression of Donald Trump, continuing to fundraise and lie about the fairness of an election that in his case, he lost by double digits. Culp does not appear in the film’s footage from the rally, but his signs do, and many of his biggest, loudest, most racist supporters are there. A couple of them flash “Heil Hitler” salutes. I found that deeply unsettling, not because I didn’t know the Proud Boys were right in my backyard, but because I hadn’t seen them…acting quite so proudly before. Cohen didn’t have to push that hard to bring that nastiness out, because it was right there, standing by.

This film also had something the original didn’t bother to establish: an emotional core. In this case, it’s Borat’s relationship with his daughter Tutar, played by Bulgarian actress Maria Bakalova. This is a remarkable performance and piece of casting, because not only did Bakalova need to perform some brilliant improvisational acting (and frankly, grifting) while speaking English as a foreign language, but she also needed to have a convincing family dynamic with Cohen while the two of them were each speaking different, mutually incomprehensible languages (Bulgarian and Hebrew respectively). It feels deeply bizarre watching these scenes, which I know to be heavily scripted and staged, but which nonetheless have genuinely affecting moments in-between all of the carefully hidden-camera-staged documentary footage. Also affecting are the scenes with babysitter Jeanise Jones and Holocaust survivor Judith Dim Evans (who passed away before the film was released), both of whom appear to have been misled about the reality of what they were participating in. These are unsettling examples of good people being shown ugly, fictitious things in order to elicit their warmth, grace, and humanity. I have legitimately mixed feelings about this (as did the people involved, some of who sued after the film premiered, and some of which have been kinda made right since?). However unsettling they may be, these scenes feel palliative for some of the ugliness on display throughout the rest of the film. Like the man said: Look for the helpers. And in a film that operates on such a bent plane of reality, the helpers are only going to show up if they believe their help is really needed. In the end, this film has already joined the first Borat in the club of movies that I find fitting for the times, laugh at in alternately sincere and mirthless ways, and definitely never want to watch again. I’m inclined to agree with Ellis’ video that we should aspire to be a society that doesn’t need champions like Cohen, however thoughtful they may seem during a press tour. But it’s still hard to look at this film as anything less than a public service, even if its exposure of that amoral fuckwit Rudy Giuliani, who has debased himself a thousand times worse every moment since this film premiered, turned out to be unnecessary.

Available on Amazon Prime here.

#10: The Platform (El Hoyo)

Directed by Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia, written by David Desola and Pedro Rivero

As concrete-cased metaphors for the excesses and deprivations of unregulated capitalism and inequality go, this one really hits the spot. The Platform takes place in a “Vertical Self-Management Center” featuring residents (two per level) who are fed once per day via a concrete tabletop that begins at the uppermost level, laden with a banquet worthy of the palace at Versailles. Each level is given one minute to eat as much food as they can, before the platform descends past them to the next level down. And so on. If they attempt to take leftovers in order to eat past that initial minute, something bad happens, let’s say. In fact, “something bad happens” is the most reliable outcome from such a scenario, precisely designed for an outcome that will chew through human lives like a stump grinder, and doesn’t particularly care. In addition to a non-zero amount of murder, rape, and cannibalism, this scenario spawns a number of memorable characters – all named, oddly, for places in Indonesia, despite all of the principal actors and filmmakers being Spanish – each of whom has a different idea about how best to participate in or reform the system. Some are just trying to stay alive. Some are trying to seize an advantage over others at any cost. Some just want revenge for their horrific circumstances. And some want to spark a revolution, if only they can find the perfect Panna Cotta.

And folks, as my prior fandom for the 2015 “vote which of the people in the room dies!” allegorical thriller Circle should make plain, I gobbled this film up even before the pandemic made it clear that my expectations of my fellow humans should be calibrated nice and low when it comes to collective action to improve our situation. Consider this fair warning: The Platform is not only a deeply disturbing and misanthropic film, but it is also unapologetically didactic and doesn’t even pretend to explain how this scenario came about organically, or what purpose it is meant to serve – some of the residents seem to be serving prison terms, others are repaying debts, and one man is apparently there for a bachelor’s degree? One particularly entertaining monologue from the character Trimagasi (Zorion Eguileor) discusses a self-sharpening knife that he bought from a late-night infomercial, and was permitted to bring inside. Another character, Goreng (Iván Massagué), brought along a copy of Don Quixote. Don’t think too hard or too long about it. Just keep hustling and scrounging and eating to survive, because this is a system that is capricious and random with its cruelty, and it’ll can pelt you down to a lower level so fast it’ll make your head spin.

Check out our podcast discussion here:

FilmWonk Podcast – Episode #168 – “The Lovebirds” (dir. Michael Showalter), “The Platform” (dir. Galder Gaztelu-Urrutia).

Available on Netflix here.

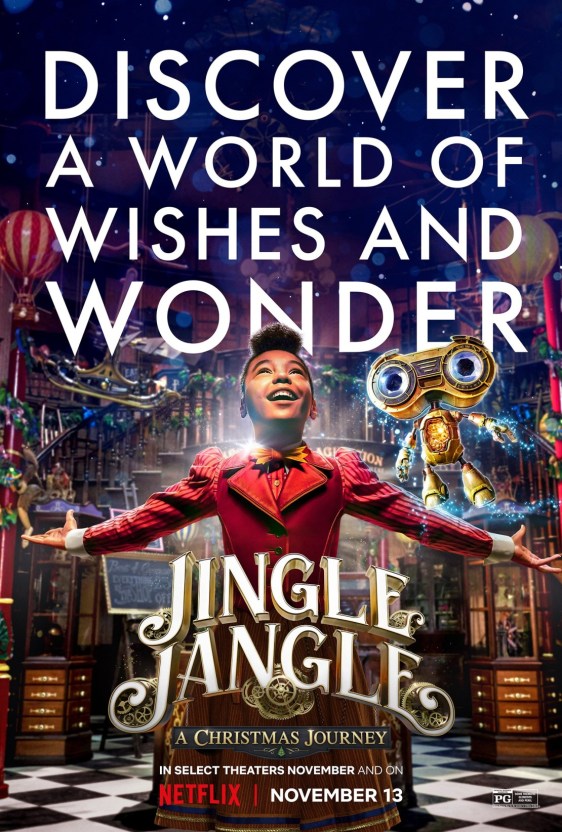

#9: Jingle Jangle: A Christmas Journey

Written and directed by David E. Talbert, with score by John Debney, and songs by Philip Lawrence, Davy Nathan, Michael Diskint, Jean-Yves Ducornet, John Legend, Krysta Youngs, and Julia Ross.

It doesn’t seem like too much to ask for black kids to see versions of themselves in a Christmas movie, but Jingle Jangle does a lot more than tick a few long-overdue demographic boxes: It is an instant classic holiday film, which was watched in my house more than once before Christmas (largely at my behest – the kids wanted to watch Elf again), and an outstanding original musical with multiple catchy, memorable songs. The stand-outs are definitely Anika Noni Rose, an experienced Disney princess and songbird who blows every other adult performer out of the water, and newcomer Madalen Mills, who is an absolute treasure as young Journey Jangle, the precocious granddaughter of a failed and dejected creator of wonders, Jeronicus Jangle (Forest Whitaker). Mills starts off what will hopefully be a promising singing and acting career with a bang, leading one of the film’s most memorable songs, as well as carrying the easy charisma that a holiday feel-good adventure story – which inexplicably involves a high-speed race through an exploding factory tunnel – requires. Most of that energy is directed at her grandfather, whom she is meeting for the first time, running a failed pawn shop after his visionary toy designs were stolen by his junior associate, Gustafson (Keegan Michael-Key, whose I’m-so-awesome intro song is a fine rendition of Harold Hill from The Music Man).

Whitaker is a fine singer (even if he’s often outmatched), but he mostly impressed me with the level of aloof whimsy he managed to bring to this character – energy that I didn’t think the actor was capable of bringing, as he has backed himself pretty well into a corner of severity for his entire career. He ends up channeling some kind of sweet spot between the secretive silence of Ben Kingsley in Hugo, and a sprinkle each of Willy Wonka (Wilder, not Depp) and Tony Stark. I mention Stark not only because of the cascade of familiar sparks and hammer-strike tinkering that make an appearance in “Make It Work Again“, but because Stark’s wraparound holographic Iron Man visuals appear repeatedly in this film as an on-screen representation of the characters’ creativity and passion. The math – whose equations literally float in the air around them and are manipulated by hand – is all fuzzy and whimsical, but the magic is all literal and real. And if you take the third derivative of awesome and pepper in some happy thoughts and serendipity, you can literally conquer gravity and float to the ceiling of your workshop. And we know young Journey has that same spark of creativity as her grandfather, because the visuals of the film convey to us that only certain people can see and do these incredible things.

The dancing, the costumes, the sets – all of it is a feast, and all of it is worth a look with the entire family. My gripes with the film were mild – Ricky Martin shows up as a sentient doll whose motivations are as ill-explained as they are ineptly executed, to sing a meandering monologue that barely qualifies as a song. But he’s little more than a chattering devil on Gustafson’s shoulder, and is easily ignored. The final act is also slightly muddled, carrying on a 30-minute denouement following the action climax that probably could’ve been tightened up. But it also contains one of the film’s best songs, and several of its best costumes and dance numbers, which is really all you need for a musical, no matter what the pace of the film is doing. Jingle Jangle was an unabashed delight, and is one of a few on this list that I expect I’ll be watching again.

Available on Netflix here.

#8: Bad Education

Directed by Cory Finley, written by Mike Makowsky, based on an article by Robert Kolker.

Small-scale corruption stories are my catnip, and this story, of what turns out to be the largest public school embezzlement in American history, is absolutely captivating. I’ll refrain from any plot details here, as watching each of the details of this scandal fall into place is a great deal of the film’s appeal, but on a basic level, I loved this film for showcasing the importance of local journalism – in this case, with a bit of irony, as the journalists who begin to unravel this plot are composited into the character of high school newspaper reporter Rachel Bhargava (Geraldine Viswanathan, of Blockers fame), whose operation is directly funded by the corrupt school district budget she is investigating, and whose journalistic integrity is alternately encouraged and threatened by every educator in her life who is eventually implicated in the scandal. Viswanathan, who was 23 during filming, walks a careful line of “tenacious first-time participant in the corrupt adult world” and “intimidated child” rather well.

Rachel begins her investigation by asking the simplest of questions: why is the school’s roof leaking? And more precisely, why is the school’s roof leaking when we apparently have millions of dollars to spend on a lavish new skybridge? I adored this for its simplicity. Because that is often how corruption is found out: regular people asking regular questions which should have regular answers. And if it takes someone longer than a sentence to answer those questions, you can be pretty sure the answer is something you’re not going to like. And when that something is the vicious cycle between unequal local school funding and the local real estate market, it’s an answer that you’ll eventually realize you knew all along.

Check out our podcast discussion here:

FilmWonk Podcast – Episode #167 – “Bad Education” (dir. Cory Finley), “Gunpowder Heart” (dir. Camila Urrutia), “NT Live: Frankenstein” (dir. Danny Boyle)

Available on HBO Max here.

#7: First Cow

Directed by Kelly Reichardt, screenplay by Reichardt and Jonathan Raymond, based on the novel “The Half Life” by Raymond.

In the 1820 Oregon Territory (at a fictitious fort on the Willamette River near modern-day Portland), Otis “Cookie” Figowitz (John Magaro) and King-Lu (Orion Lee) strike up a friendship through the most random and brutal frontier circumstances: King-Lu is hiding from a group of Russian fur trappers, on the run for killing one of them (in self-defense, he says – but we only have his word on it). And Cookie, who is camping with another trapping crew, offers him his tent to hide and rest for the night. The next morning, they go their separate ways, but they meet once again at the fort and King-Lu offers to return the favor, giving Cookie a place to stay while they figure out their next move, which turns out to be a nice warm friendship on the frontier, followed by what seems like it should be a harmless plot involving the first dairy cow in the region (Evie the Cow), owned by the company boss Chief Factor (Toby Jones), a right honourable gentleman in the finest English tradition who just wants some milk in his tea.

First Cow is a film of contradictions. It is quaint, but worldly. It is limited in its scope, but allegorical. It is nasty and violent, but also imbued with a persistent sense of warmth and peace. It is a throwback to a little-explored period in the Old West, but plants one foot firmly in the modern day, opening on a scene with a woman (Alia Shawkat) walking her dog, who happens upon a pair of ancient skeletons along the river as a modern metal container ship floats by. The message of this ship broke through to me loud and clear late in the film: this region has been conquered. There is scant presence of the local Natives, including Totillicum (Gary Farmer) and Chief Factor’s unnamed wife and translator (Lily Gladstone), who seem present solely as witnesses to the fact that civilization existed here before the white people came to try and recreate their own, and to remind them that their struggles to recreate the tastes of London and Boston could have been better spent if they’d simply taken the time to listen, learn, and share. But they came with a rapacious desire to make their fortunes and extract resources – initially beaver pelts to serve the Paris fashion scene, and eventually timber and ore, as they tried all the while to recreate the lives they had left behind.

Cookie and King-Lu’s friendship (and their low-stakes caper) is a small story to focus on, but it’s also a very sweet one, and the more we linger on their warm connection and sharing of their lives together amid an uncertain future, it feels more and more important and resonant as the film goes on. Following the Pompeiian* image of a pair of unknown skeletons resting peacefully by the river, it is an image that conjures up both hope and despair. Because the violence of this film, both individualized and structural, didn’t have to be this way – it’s simply the way it was. And we must remember that we make our homes, amid the escapist tunes of not one, but two bucolic, cottagecore Taylor Swift albums this year, upon the bones of history. Most stories like this one are lost forever. First Cow is a work of fiction, but it is a plausible story. And it inexorably conjures up the idea that there must have been many others like it, whose names and faces will never be known.

* Props to co-host Erika for conjuring up this image on the podcast

Check out our podcast discussion here:

FilmWonk Podcast – Episode #178 – “Promising Young Woman” (dir. Emerald Fennell), “First Cow” (dir. Kelly Reichardt)

Available on Showtime here.

#6: Sound of Metal

Directed by Darius Marder, written by Darius Marder and Abraham Marder

Riz Ahmed deserves every ounce of the praise he’s getting as Ruben Stone, a heavy metal drummer who has to deal with the massive upset to his life that is sudden onset deafness. His career, relationship, and sobriety – he is an addict, a few years sober – are all suddenly at risk, and he knows it. His girlfriend and bandmate Lou (Olivia Cooke), with whom he shares a few quiet moments of roadtrip domesticity in their band’s RV before his hearing begins to intermittently drop off, is able to get Ruben into a program run by Joe (Paul Raci), an accomplished ASL interpreter, lip-reader, and social worker who lost his hearing as an adult due to a war injury in Vietnam.

Ruben is in a difficult situation, and his guilt leads him to rash and occasionally self-destructive impulses that pre-date – and are likely a partially contributing factor to – his deafness. He is also in a romantic relationship that is highly intertwined with a theatrical pursuit (heavy metal is nothing if not a great big show), and coexists with every vice that he is now looking to avoid, from opiates to dangerously loud noises. This film takes place in Ruben’s moment of crisis, which is both the stuff of serious drama and a story that is inherently difficult to tell. The film offers dual avenues into Ruben’s mind, and the first is its borderline experimental sound design. 2020 was a year of streaming by necessity, and this film was picked up by Amazon Studios before anyone knew there would be a viral pandemic. And yet, this film feels precisely as if it was made to be watched in this way, subtitles and headphones on, trying our best (along with Ruben) to follow what’s happening as the sound distorts and drops out for character and the audience alike. The second avenue is, of course, Riz Ahmed’s stellar performance. Ahmed is an accomplished British actor who managed to break out of the post-9/11 conflicted-terrorist pigeonhole that he found himself thrust into and did some amazing work in (Four Lions is a masterpiece). He is also a rapper and MC of some renown, and he manages an American accent here that seems to be channeling Aaron Paul in Breaking Bad, which feels exactly right for a character accustomed to others’ low expectations, who is suddenly forced to deal with a situation that absolutely no one can get him out of. He rages, he flails, he writes down his emotions (and occasionally speaks them aloud) at Joe’s direction, but we mostly just have to guess at how he’s feeling as we watch Ruben’s face, straining, but never cracking, as he beats furiously on drums that he will never be able to perceive the same way again. He’s not quite drawing Whiplash-level bloodshed, but he’s clearly at war with himself in a similar way.

Joe speaks at greater length than Ruben ever does, as he is decades into his hearing loss and clearly at some manageable level of peace with himself. Raci – a hearing actor who grew up with Deaf parents – plays Joe as an aspirational figure, but not as any sort of simplistic mentor archetype. He sincerely wants to help Ruben, but he is also clearly a veteran of many unsuccessful attempts to help people like him. He is prepared to fail, but he will give everything of himself to try and help Ruben succeed. And watching this relationship develop is a great deal of the film’s appeal.

The target audience for this film is clearly the hearing community, for whom this serves as a primer on the both the medical options as well as the cultural, practical, and social resources available within the Deaf community. I’m choosing my words carefully here, because as a friend and family member to multiple individuals with disabilities, I know these issues are fraught, individualized, and there are differences of opinion even within their respective communities about how people with disabilities should live their lives. This film has a few specific things to say about cochlear implants, a device available to some people with hearing loss which can help them understand speech, but doesn’t offer any easy answers about whether these implants are the right choice, and makes it clear that there are those within the Deaf community that have fairly strong opinions about them.

Available on Amazon Prime here.

#5: Lingua Franca

Written, directed by, and starring Isabel Sandoval

This is Isabel Sandoval’s fourth feature, but her first with this name, since transitioning. I didn’t think long on how to write those details, except that “debut feature” didn’t seem right (as the technical aspects of this film are clearly a product of experience and skill), and the film is similarly matter-of-fact about issues of sex and gender, as well as race. It was this mishmash of identities that I understood to be one possible meaning of the title, Lingua Franca. These categories exist as a common language and set of assumptions, and they are bolstered by a set of legal and cultural frameworks that some people bear a disproportionately high burden for, because they don’t fit precisely within an expected mold. So it is for Olivia, a trans Filipina woman who is in the United States without legal status, and is in the process of arranging – on a fee-for-service basis – a green card marriage with an American man. Olivia’s passport still bears the name and sex she was assigned at birth, and it is somewhat of a political irony that the United States’ legalization of same-sex marriage in 2015 made this situation a bit legally easier to manage than it might have been otherwise – or at least than it would have been back home, as we learn that trans people face many similar hurdles in the Phillippines to the United States, including the lack of a national legal process to change their gender on their identity papers. Olivia works as a caregiver for an elderly Russian woman, Olga (Lynn Cohen, in one of her very last features before she passed last year), whose black-sheep grandson Alex (Eamon Farren) has just been given a last-chance job at the family’s butcher shop, on the condition that he help out with Olga’s care as well. So Alex is now an interloper for the job that Olivia is being paid to do. He quickly takes a shine to her, and the feeling seems to be mutual. And then the lingua franca takes on an additional meaning: love is a language that we all speak in one way or another, and yet it is quickly clear what potential peril Olivia is in, as a man who clearly does not know the totality of her circumstances and background, and may or may not react negatively to learning about them, is suddenly thrust into her path. She has to decide how much she wants to engage with their slowly burgeoning romance, when she has, frankly, more important things to worry about.

That’s really what made this film immediately work for me: it felt less like, as Sandoval put it in an interview, “Trans 101” – it felt instead like meeting any trans person I’ve ever met, or, for that matter, any cis person I’ve ever met. She’s there, she’s living her life, and the details about that life come out organically as she feels like sharing them. Or they don’t, if she doesn’t. Her romance with Alex is initially presented as a sort of best-case scenario for a romance that could go wrong in any number of ways, including deportation. And as we get to know Olivia, so we learn the fundamental truth that even if every aspect of her identity and circumstances are not readily apparent, and will not be shared until such time as she feels like sharing them, they are a part of her in every moment, as is the peril (both to her physical safety and her life in the United States) that comes along with them. Alex has plenty of opportunities to step on his toes while navigating that, lovable fuck-up that he is, and it is very much a source of the film’s tension which of these competing tendencies will win the day. Because Sandoval plays Olivia as her own precious creation: a self-possessed woman who is not to be trifled with, because such trifling runs a very real risk of destroying her life.

This film is unavoidably fraught with moral complexity, but it is also just a sweet and well-told romance, and ultimately one that deserves greater attention than it has gotten. Because whether Sandoval wanted Lingua Franca to be Trans 101 or not, surveys have shown that exposure to trans people leads to increased tolerance of their existence, and that tolerance literally saves lives. And seeing and engaging with a thoughtful romance starring a trans woman of color will, whether it rightfully bears that burden or not, save lives.

Check out our podcast discussion here:

FilmWonk Podcast – Episode #174 – “Mulan” (dir. Niki Caro), “Lingua Franca” (dir. Isabel Sandoval), “Up on the Glass” (dir. Kevin Del Principe)

Available on Netflix here.

#4: Wolfwalkers

Directed by Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart, written by Will Collins

I’ll start with a humblebrag. When I tweeted my sentiment that Wolfwalkers, which I saw near the end of last year on AppleTV+, is “cool as fuck”, the tweet’s first two likes were from Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart, the two directors and principal artists at Cartoon Saloon who made this film happen (along with a vast crew that worked on it over seven years). I’m trying not to overread these gentlemen noticing my interest in their lovely film, but my impression is that AppleTV+ is on the smaller end of streaming audiences, and the idea of a film with such a gorgeous and unique animated vision being a buried, little-seen launch title feels a bit sad to me. Because Wolfwalkers IS cool as fuck, and it’s an effort that deserves a wider audience.

The year is 1650, and Robyn Goodfellowe (Honor Kneafsey) is an adventurous English girl, daughter of Bill (Sean Bean), a hunter who aims to trap and kill every wolf in the woods surrounding Kilkenny, Ireland, with the ostensible purpose of protecting the people, but with the usual human justifications (livestock, expansion, a general desire not to coexist with nature). Wolves have a prized position in Irish folklore and culture, and this film uses that folklore to cast a narrative lens onto a series of real events and laws that were enacted during Oliver Cromwell‘s conquest of Ireland, which culminated in the complete extermination of all wolves in Ireland. In Wolfwalkers, the focus is on a single Irish village, and its domination by an English noble known only as the Lord Protector (Simon McBurney) – a clear stand-in for Cromwell – who enforces a harsh outsider’s set of rules upon the Irish people and their ways of living. This familiar story quickly merges with contemporaneous legends of werewolves, skinchangers, and other complex hybrids or relationships between humans and wolves, as Robyn meets a friend, Mebh (Eva Whittaker), a girl who lives in the woods, seemingly in charge of a wolf pack, and her mother Moll (Marie Doyle Kennedy), who sits in an endless and initially unexplained slumber. Mebh is an absolutely wild thing. She adores her life, which she spends half as a girl and half as a wolf, but she is also naive about what a serious threat her pack faces from the English hunters. The relationship that develops between Robyn and Mebh is both tender and complex, with Robyn (and to a lesser extent, Bill) torn between their duties to the Lord Protector and the town, and their burgeoning relationships with the people (and people-adjacent skinchangers) right before them. The two obvious and facile comparisons are Avatar and Brave (for anyone foolhardy enough to say that Scottish folklore is interchangeable with Irish), but the 2002 Christophe Gans film Brotherhood of the Wolf came to mind as well, for the seamless way that screenwriter Will Collins put a freeform lens onto some complex real-world history and politics, mixing in contemporaneous folklore, and merging both threads for the particular story and audience he wanted to pursue. Brotherhood is very much not for children, but it operates on a similar narrative wavelength.

Combine all of that with an absolutely unique and dazzling animated vision of the Irish countryside, and Wolfwalkers is comparable to the likes of Studio Ghibli, not for visual similarity to that studio’s work, but for specificity: the look and feel of a Cartoon Saloon film is consistent and unique, with a mix of what seem to be water colors and layered two-dimensional planes (almost like the sorts of gorgeous carved and painted wooden panels you might find in medieval churches), but with some surprising depths to it – including a number of exhilarating sequences in which we see the world through the senses of wolves running through it, following scent and heat trails. This is a glorious assault on human senses that could only have worked in an animated medium, and the sort of experiment in form that I always enjoy seeing.

…which is why it’s cool as fuck.

Available on AppleTV+ here.

#3: The Vast of Night

Directed by Andrew Patterson (in his feature debut), written by Patterson (credited as James Montague) and Craig W. Singer.

We begin The Vast of Night wandering around the tiny (fictitious) ’50s town of Cayuga, New Mexico with a couple of crazy kids, AM radio DJ Everett Sloan (Jake Horowitz) and switchboard operator and amateur tape-recorder Fay Crocker (Sierra McCormick), who slowly become enveloped in a mystery. This happened to be one of the first theatrical films that I watched in quarantine, and the film’s long opening shot through the town’s great big Friday night to-do, the high school basketball game, certainly made for some vicarious enjoyment of the mere idea of doing things with other people again. But I’ve watched this movie twice since, and not only do its crisp 91 minutes fly by, but I had an ear-to-ear grin on my face the whole time, largely because of the film’s elaborate single-shot walk-and-talks and the unrelenting charm of these actors and this town, both individually and with one other.

Everett and Fay are instantly charming and disarming, and they settle into a naturalistic patter with the entire town that is rife with ’50s slang and instantly makes the town feel lived-in and full of people who’ve known each other their whole lives. This isn’t the same genre or ambiance as Rian Johnson‘s Brick, but it demonstrates many of the same skills. Patter is hard. What’s also hard, I assume, is operating 60-year-old radio and telephony equipment, but McCormick and Horowitz not only carry two extremely long scenes doing exactly that, and they clearly put the time in to make it look as if they’d done it a thousand times. Bravo. There is so much lazy object work in much more expensive films than this, and these scenes were as engrossing for the burgeoning mystery unfolding one phone call at a time, as for the work the actors and production designers clearly put into making those calls and moments feel authentic. I say again: Bravo. Fay’s scene at the switchboard is easily 9 minutes long, and spends that time both building tension and establishing the details of the film’s central mystery, involving a mysterious auditory signal “bouncing around the valley tonight”. The signal hits phone lines and radio waves alike, and Everett puts out the word over the airwaves that they’re looking for more information about it. And information is what they get. To prepare the way, this scene is followed with a cross-town ground-level camera saga (which apparently involved a go-kart, a technique that DP Miguel Littin-Menz claims was inspired by Lawrence of Arabia), which plays beneath a howling wind and scant central street lights as the musical score builds. The camera takes on the feel of a predator stalking this sleepy burg while its people are all packed away in a warm gymnasium, where the camera briefly slows down and the colors get warm as we watch the game go on, the ball bounces, the commentators talk, and the town cheers, all without a clue what might be waiting for them outside. Then…out the camera goes, passing through a window at the top of the bleachers and resuming the chase.

Slow-burn tension is the name of the game, and this sequence is about as close as the film comes to real menace and horror, of the Twilight Zone sort. Or, literally, Paradox Theatre, which the film uses as a fictitious TV-show framing device. It was kind of a hat on a hat at that point, but I didn’t mind. As the auditory mystery unfolds and the town starts to wonder if the swirling skies are watching them back, I never doubted for a minute that these two are perhaps the only ones in town who can solve the mystery in time to save their town from whatever danger may be afoot just offscreen. The resulting vibe really only exists in podcast form these days, but used to come crackling over the airwaves while driving down the highway at 2AM, nary a light in sight, with the pleasant voice of the late, great Art Bell playing over your car stereo, wishing you a safe drive home, but telling you to watch out – because you never know what’s out there.

Check out our podcast discussion here:

FilmWonk Podcast – Episode #169 – “The Vast of Night” (dir. Andrew Patterson), “Holy Motors” (dir. Leos Carax)

Available on Amazon Prime here.

#2: Palm Springs

Directed by Max Barbakow (in his feature debut, written by Andy Siara.

“It’s one of those infinite time-loop situations you might’ve heard about.”

“I might’ve heard about?”

Nearly three decades on from Groundhog Day, we were due for another existentially daunting romantic comedy, and it was surely to this film’s advantage that it happened to come out in a year in which every day was the same and nothing mattered, except for those choices which might lead to dying alone in the ICU. Palm Springs, which dropped on Hulu on the closest thing to a summer blockbuster weekend that we were able to have this year (releasing concurrently with superhero drama The Old Guard and the fx-fueled Tom Hanks historical epic, Greyhound). I watched all three films, but this is the one I enjoyed the most by far, and the reason had as much to do with the film’s accidental fitness for pandemic viewing as it did with its effectiveness as an uproariously, darkly hilarious romance. By the time we meet Nyles (Andy Samberg) he has already spent the last [very long time, perhaps centuries] as an ancillary participant in a wedding where his cheating girlfriend is one of the bridesmaids. This is one of many fascinating dynamics created by Nyles’ status as an old soul at the start of the film (and one of several ways in which it accidentally resembled The Old Guard) – he adopts a Puckish persona, aloof, impressive to others but only when he feels the need to be, and never getting riled up about the same sorts of things as we mere mortals. Not only has he had a chance to get to know everything that there is to know about this time and place, but he has also grown beyond the things that we care about: love, money, sex, and death – which are just not as important when you’re an untouchable Time Lord, and also operate on completely different moral planes. This is a fascinating performance from Samberg because as he cracks jokes with Sarah (Cristin Milioti), who is new to this particular existential sinkhole, I really got the sense that he was emerging from an alcoholic malaise that he hadn’t felt any particular need to come out of for years (or maybe longer). For this particular immortal, with nothing new to contemplate, the most attractive characteristic of Sarah (the sister of the bride, whom he knows a great deal about already) is that she’s new, and is thus unpredictable and uncontrollable.

Milioti, meanwhile, plays Sarah as a woman put-upon at the start by both her own past behavior and others’ judgments (“They all see me as a liability who fucks around and drinks too much…because I fuck around and drink too much”), as well as the knowledge that she’ll never escape a day that she simply can’t feel as aloof about as Nyles. This is both their fundamental attraction and their fundamental disagreement: She sees the appeal of his gleeful nihilism in the situation that they’re both stuck in, and even embraces it for a while. The couple has plenty of time to get accustomed to each other’s patterns, which is the sort of metatextual definition of human companionship that could only come about through a complete absence of material concerns or fear of death. As such, it should come as no surprise that I lifted it from Star Trek (a utopia which explicitly relies on a lack of conventional fears and needs), but it’s also an elegant metaphor for both romantic commitment and life itself. Because these two aren’t spending their lives together – that is impossible as long as they’re stuck in a place where time has no meaning, and their actions have no consequences, except to each other. The conflict over whether they would choose each other over everyone else in the world if they had a meaningful choice about that is a purely academic one as their romance begins to bloom. And this is exactly how Palm Springs innovates on the Groundhog Day formula: the film doesn’t treat its love interest as a disposable amusement for a lonely god, free to choose her level of participation, but only on a fleeting basis, with the god free to simply try her again the next day. Palm Springs eschews this framework and treats it as an aspect of Nyles’ temporal cage that he has come to loathe. The film invites both participants to be fully cognizant of their shared reality, and have a real choice about whether or not this love is worth continuing, if and when leaving it behind ever becomes an option. Which sure feels a lot sweeter in retrospect.

Also, J.K. Simmons is at his usual level of quality, even if I can’t say much about his character here.

Check out our podcast discussion here:

FilmWonk Podcast – Episode #171 – “Palm Springs” (dir. Max Barbakow), “The Old Guard” (dir. Gina Prince-Bythewood)

Available on Hulu here.

#1: Da 5 Bloods

Directed by Spike Lee, written by Danny Bilson, Paul De Meo, Kevin Willmott, and Lee.

The African-American novelist and cultural critic James Baldwin once wrote the following, following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.:

“Perhaps even more than the death itself, the manner of his death has forced me into a judgment concerning human life and human beings which I have always been reluctant to make….Incontestably, alas, most people are not, in action, worth very much; and yet, every human being is an unprecedented miracle. One tries to treat them as the miracles they are, while trying to protect oneself against the disasters they’ve become.”

I read this quote between my two viewings of Da 5 Bloods, and it comes inexorably to mind as I ponder these four men now. In particular, Paul (Delroy Lindo), whom we quickly learn is barely keeping it together on his first trip back to Vietnam since he fought in the war. He returns to the country with his three Bloods – fellow black soldiers from his squad, who forged a familial and racial bond from their unique experiences in warfare. These men are ostensibly returning to Vietnam in the modern day to repatriate the remains of their fallen Blood, Norm “Stormin’ Norman” Holloway (Chadwick Boseman), as well as (secretly) a planeload of CIA gold that had been requisitioned to pay the local Lahu people to fight against the VC, and was subsequently lost in a plane crash and buried by these five men for later retrieval.

The Baldwin quote came to mind not just for its resonance with respect to Paul, but because of one scene in particular, layered with both visceral rage and brotherly love, in which Dr. King’s murder is revealed to the five main characters as they camp in the jungle. They are seemingly separated from any other unit or chain of command as they listen to a propaganda broadcast from Hanoi Hannah (Veronica Vanh Ngo), who is playing out a psychological warfare strategy of trying to persuade American G.I.s of the immorality of warfare, and trying to persuade black GIs in particular to give up the fight for a country that has never properly embraced them as full citizens. This scene feels both theatrical and plausible as it is playing out, with the five men seemingly just camped in the jungle with no specific mission, all played by men in their 50s and 60s (who aren’t quite old enough to play these characters in 2020), with the exception of then 42-year-old Boseman (who passed away from colon cancer in August). Norm is only partially in uniform, standing before a jury-rigged sunshade of ferns, and the camera floats over each man’s face as they take in this devastating news, fading back and forth over footage of King’s funeral procession and riots in over 100 American cities. Hannah continues, pointing out that black people are only 11% of the US population, but they represent 32% of the American troops in Vietnam – depending on the specific year, this seems to have been both a true statistic and a deliberate strategy by the US government, and Hannah suggests that they should go home and fight where they are really needed.

Theatricality was a stylistic choice that the film announced early on, with its periodic cutaways to footage of real events (including Donald Trump in Da White House, a key component of the film’s modern resonance), as well as intermittent bits of Sorkinesque historical exposition in dialogue, in which characters just randomly call out bits of (black) American history in order to educate the viewer about the likes of Crispus Attucks (who died at the Boston Massacre in 1770), one of the first black soldiers to die in the name of the American Revolution, and a name I hadn’t heard since high school. And other names I’d never heard at all, like Milton Olive, a decorated hero of the Vietnam War who posthumously received the Medal of Honor after dying at just 18, falling on a grenade to save his squad. None of this bothered me in the least, coming in fits and starts during a solid 35-40 minutes of character setup in Ho Chi Minh City at the start of the film, both because it was entertaining in the moment, and because it announced the film’s intentions to be about something greater than just Heart of Darkness meets Three Kings – comparisons the film is also keenly aware of. Da Five Bloods is about the extent to which these men’s experience of war, loss, racism, and bitter disappointment has cast a pall over their lives, and threatens to drag them on a desperate, greedy march to the grave. The film starts with a pretense of vacation with a dash of heist caper, and has some genuinely raucous action beats. But it slowly reveals itself as a return to a demon-haunted world.

As Otis (Clarke Peters) tees up this flashback in order to explain to young blood David (Jonathan Majors) exactly who and what Norman was to the group, and to David’s father Paul in particular, he describes him like this:

“Stormin’ earned his name – was in all kinda fire fights. Trained us in the ways of the jungle. Made us believe we’d get back home alive. He was a prophet. Gave us something to believe in. A direction, a purpose. Taught us about Black History – when it wasn’t really popular back then. Schooled us about drinking that anti-commie Kool-Aid they were selling. He was our Malcolm and Martin. Norman had a way of keeping us from going off.”

Right before this flashback is a scene in which Vietnamese soldiers are tramping through the jungle talking to each other – about their sweethearts and wives back home, which we know because the dialogue is subtitled – an uncommon choice in an American war film. We consume a bit of the enemy’s humanity before we watch our heroes rise up from the bushes and riddle them with bullets. Da 5 Bloods are soldiers, who will do their duty, but they are also thoughtful men, seekers of enlightenment, who have found a leader who wishes to imbue them with his own brand of righteousness. Of the group, only Norm seems fully cognizant of what they’re doing in this country, explicitly framing war as an economic act. He is also the only one who seems to understand that Hannah’s broadcasts are tailor-made to anger them specifically. As he meets their violent and unfocused rage, which promises to murder the nearest cracker they can find – surely a fellow American soldier – Norm stands in their way. Says that Dr. King was a man of peace, who wouldn’t have wanted this. He meets their rage with love, as they all stand together with righteous fury and blast their M-16s skyward. Theatricality.

Norm is subject to many beatific praises throughout the film, including many direct and indirect comparisons to Jesus Christ, but the one that really stuck with me was “He was our Malcolm and Martin.” This evokes a dichotomy that is often used as dismissive shorthand (by white people) when discussing the struggle for black liberation, in which Malcolm X is used to represent the militant side, and Dr. King is used to represent the peaceful side, confining his rhetoric to non-violent appeals to equality and colorblindness amid peaceful civil disobedience. I can’t speak for Lee or co-writer Willmott here (who wholly rewrote this film from a 2013 spec script that originally had nothing to do with black history), but my impression is that this line was meant to carry some irony for a black audience that would understand that neither Malcolm nor Martin can be so cleanly summed up, as anyone who has read any of their writings can attest. As a white man who came of age long after both men were dead, and who grew up steeped in the myth that the mid-century struggle for civil rights ended favorably, I am not qualified to speak with any authority on this subject, but I have tried to cultivate a more realistic understanding of it as time goes on. I grew up in a world in which the predominant political discourse, until very recently, was always some variation of “When will black people be satisfied?” With President Obama’s election, even as the birther lies and mock-lynchings continued, White America echoed a refrain that Dr. King’s work was over a long time ago (even as a handful of their number always whinged that Black History Month was racist). The civil rights movement was a triumphal narrative that ended with the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 – the very same law which I watched a conservative Supreme Court bloc eviscerate in 2013, which was followed by a giddily resurgent neo-Confederate South – now calling itself the Republican Party, but with a through-line since Reconstruction that spanned both parties – which began attacking black voters “with surgical precision“. The GOP began using voter suppression techniques straight out of the Jim Crow playbook on Information Age steroids, in order to perpetuate minority rule (for the dwindling bloc of rural, conservative white people) into the future. The idea that black people can ever be “satisfied” with our meager pretense of a post-racial society, which was never built in a way that offered them anything close to a fair chance, has always been a lie. And as I attempt to make sense of Lindo’s career-best performance of this black man in a MAGA hat, I firmly believe that this character represents Spike Lee‘s brilliant attempt to grapple with the damage that this lie has caused.

So we have Paul, the Vietnam Veteran with untreated PTSD and a 30-year-old son that he doesn’t understand and can’t relate to, rabid supporter of one Donald J. Trump for president. That’s right – Paul voted for President Fake Bone Spurs. That his fandom for Trump’s cruel (but nonetheless revelatory) brand of American conservatism is presented as a part of his post-war pathology doesn’t change the surprising fact that this is one of the only films that I’ve seen credibly try to get inside the head of a Trump supporter, which might be about the last thing anyone wants to do after watching their QAnon-addled miscreants storm the US Capitol this month. And yet, it is necessary, and a significant part of what makes this film such essential viewing. Boseman’s death is one of many unfortunate ways in which the film’s release accidentally interacted with the trying times of 2020, with the film coming out in June, near the crescendo of protests over the brutal murder of George Floyd at the hands (and under the knee) of now ex-police officer Derek Chauvin, and under the watchful eye of his colleagues at the Minneapolis Police Department, who did nothing to stop him. Another name, another protest, another black life that didn’t matter. Another police response that proved the protesters’ concerns about police brutality and lack of accountability a hundred times over, from coast to coast and for weeks on end.

It may seem as if I’ve wandered afield from the text of this film. And perhaps I have. After 11 years of reviewing films on this site, it has been quite as much about keeping a public diary of the ways in which my own thinking has changed, as it has been about chronicling and reacting to popular culture. Make no mistake, Da 5 Bloods is my #1 film of the year for the same reason as any previous film: I haven’t stopped thinking about it since I saw it. But I found myself unable to make much progress writing during this month in particular, as our republic and collective sense of reality reached a Trump-instigated, collectively-perpetrated attempt to rip itself to pieces. So it was inevitable that all of this real-world bullshit would become entangled with my feelings about Paul the fictitious Trump supporter. We find ourselves halfway through an ineptly handled pandemic, barely out of the twilight of President Fake Bone Spurs, a wannabe election thief and incompetent fascist who turned out to be too lazy and unskilled to pull off the coup d’état that he clearly had no moral or patriotic compunction against attempting. I may have seen this film at a conveniently receptive time, but it is about much more than just these four men and their self-destructive struggle to enrich themselves on the backs of the very same war machine that had so thoroughly damaged each of them. This film stuck in my craw at the same time, and for many of the same reasons, as the struggle against systemic racism and police brutality this year, and both have refused as yet to leave me behind. When I first saw Da 5 Bloods, I had scarcely even heard of James Baldwin (whom I quoted above), and most of my knowledge of him now is secondhand, presented through Princeton professor Eddie S. Glaude, Jr.‘s scholarship of Baldwin’s work, and his modernization of Baldwin’s notion of “The Big Lie”. Michael Harriot takes this further, asserting that the Capitol Rioters may have pretended to attack our nation’s institutions over a small lie, that Trump won an election he factually lost, but they were doing so in service of a bigger lie: That White America is willing to accept the results of an election in which the usual insidious mechanisms of voter suppression were swept aside by the COVID pandemic, and black Americans are finally free to assert their political will.

Even as I am distracted and enraged by the Capitol Rioters: by their racism and violence, by their presumption, by their warped pretense of patriotism that has little or nothing to do with the material circumstances of the actual people who live in the actual United States, and more to do with the wholly symbolic cosplay that they pathetically call freedom – I can’t let go of the country that made it happen, whose real-time mythologizing of its own history is the reason why we’re still having inane conversations in 2020 about whether or not it’s appropriate to honor Confederate traitors with statues in public spaces. As we dance on endlessly to a tune first played by dead men, I truthfully can’t damn the Capitol Rioters (as much as I will relish seeing many of them behind bars), because the ugliness they presented as they bore their collective ass for us all to see, is America. Paul, in this film, is us. As Delroy Lindo says directly to the camera: You can’t kill Paul. And I can’t damn him either.

I’ll close with this quote, from Glaude’s excellent book Begin Again, which has become a sort of guiding star as I think of how to approach the after-times of Trump.

“[T]he desire to distance oneself from Trump fits perfectly with the American refusal to see ourselves as we actually are. We evade historical wounds, the individual pain, and the lasting effects of it all. The lynched relative; the buried son or daughter killed at the hands of the police; the millions locked away to rot in prisons; the children languishing in failed schools; the smothering, concentrated poverty passed down from generation to generation; and the indifference to lives lived in the shadows of the American dream are generally understood as exceptions to the American story, not the rule…To maintain this illusion, Trump has to be seen as singular, aberrant. Otherwise, he reveals something terrible about us. But not to see yourself in Trump is to continue to lie.”

Check out our podcast discussion here:

FilmWonk Podcast – Episode #170 – “Irresistible” (dir. Jon Stewart), “Da 5 Bloods” (dir. Spike Lee)

Available on Netflix here.

Theatrical Hits from the Before Times

Films that I recall enjoying enough to be considered here, but which a year of COVID and political chaos has effectively driven from my memory.

- Bad Boys for Life (directed by Adil & Bilall)

- Birds of Prey (directed by Cathy Yan) (podcast)

- The Invisible Man (directed by Leigh Whannell) (podcast)

Honorable Mentions:

- Soul (directed by Pete Docter) (available on Disney+)

- Never Rarely Sometimes Always (directed by Eliza Hittman) (available on HBO Max)

- Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (directed by George C. Wolfe) (available on Netflix)

- Promising Young Woman (directed by Emerald Fennell) (podcast) (available on PVOD)

- Small Axe: Red, White and Blue (directed by Steve McQueen) (available on Amazon Prime)

- Cargo (directed by Arati Kadav) (podcast) (available on Netflix)

- Kajillionaire (directed by Miranda July) (podcast) (available on PVOD)

- Possessor (directed by Brandon Cronenberg) (podcast) (available on PVOD)

- Get Duked! (directed by Ninian Doff) (review) (available on Amazon Prime)

- Same Boat (directed by Chris Roberti) (podcast) (available on Tubi and PVOD)

- The Devil All the Time (directed by Antonio Campos) (podcast) (available on Netflix)