This review originally appeared as a guest post on 10 Years Ago: Films in Retrospective, a film site in which editor Marcus Gorman and various contributors revisit a movie on the week of its tenth anniversary. This retro review will be a bit more free-form, recappy, and profanity-laden than usual.

“While I will readily admit that Cloud Atlas is not for everyone, I look forward to defending this masterpiece for years to come.”

-Me (2012 Glennies, #1)

I KNOW. Where I normally excerpt a segment of first-person voiceover (and there is plenty to choose from in this film), I just quoted myself lauding this movie. But in the insipid words of publisher Timothy Cavendish (Jim Broadbent), what is a critic but one who reads quickly, arrogantly, but never wisely? Just as with Birdman, I reacted to a group of creators showily condemning their haters in advance with a dutiful and masochistic, “Thank you, folks, may I have another?” And Cloud Atlas went even further, pitching its knighted critic Felix Finch (Alistair Petrie) straight off a hotel balcony, before delivering on every bit of cocksure brilliance that moment promised was still to come. After 10 years, I still greet a viewing of Cloud Atlas like a reunion with an old friend, and I have not wavered in that opinion since the moment I saw it. I’ve spent years swimming in Tom Tykwer, Johnny Klimek, and Reinhold Heil‘s wondrous, symphonic score for the film, which I’ve listened to so many times during so many activities that I need only put it on to become tangled in a semi-coherent yarn of my own interconnected memories of the past decade (it’s a thing – try it sometime if you have the memories and repetitive media consumption for it). I’m listening to that score right now, the very same Cloud Atlas Opening Title that plays as Adam Ewing (Jim Sturgess) approaches Dr. Henry Goose (Tom Hanks) on a 19th century beach in the Chatham Islands as we are introduced to the first of six sets of characters and parallel timelines spanning hundreds of years, covering the technological rise and fall of humanity as they struggle against their baser demons, represented initially by humans volunteering to uphold the “natural order” (this always means racism, slavery, and genocide) and eventually by a hallucinated devil figure named Old Georgie (Hugo Weaving), who cackles into the ear of post-apocalyptic Big Island goatherd Zachry (also Hanks) trying to persuade him that being racist and violent is a more important priority than evading Cannibal Hugh Grant (Hugh Grant) and the impending creep of global radioactive demise. Does this premise have your attention yet? Because that’s maybe 25% of it. We also meet Sonmi-451 (Doona Bae), a “fabricant” (a cloned or manufactured human) who works as a server at a fast food restaurant called Papa Song’s, in the 22nd century megacity of Neo Seoul, the seat of a dystopian government called Unanimity, a rebellion called Union, and doomed to be “deadlanded” by the time Zachry and Cannibal Hugh Grant are picking their way through Earth’s remains.

Papa Song’s is so thoroughly automated that it’s clear the synthetic servers are not necessary, except to make the consumers feel like kings surrounded by disposable human-shaped playthings as they eat 3D-printed garbage (which looks tasty at least). We learn that the fabricants get a star on their neck for each year of service. When they reach twelve stars, that means it’s time to get recycled into chum – known as “Soap” – to feed the baby-synths. Sonmi explains to us that each 24-hour Papa Song day is the same as any other, which makes it even more disturbing when Seer Rhee (Grant) awakens another fabricant, Yoona-939 (Xun Zhou), the closest thing to a friend that Sonmi has in this place. He awakens her for sex (of the sort she tolerates, but can’t meaningfully consent to), and to get soused on Soap. After Rhee has passed out in a puddle of his own sick, Yoona takes advantage of the hours of freedom that it affords her to poke through the lost and found and see a bit more of the world outside – in this case, via a broken and absurdist movie rendition of The Ghastly Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish, in which an actor (Tom Hanks again) plays Cavendish as a rugged hero – “equal parts Sir Laurence Olivier with a dash of Michael Caine” – telling a corrupt proprietor (whose name and context we don’t even know yet), that he “will not be subjected to criminal abuse”. As 19th century Moriori slave Autua (played, somewhat bafflingly, by Black British actor David Gyasi) recounts to Adam Ewing aboard their ship in the Pacific, a slave who has seen too much of the world is no slave at all, as Yoona learns anew 300 years later. That’s the hopeful version, anyway. It can be interpreted just as readily that humans have a particular adeptness at reciprocal violence, with aggression and enslavement being answered with the same, always pointing back to some original sin to justify whatever excesses we feel like engaging in. As Cannibal Rob Corddry (not really, but I couldn’t tell you this actor’s name) puts it while trying to murder Zachry, “You kill Chief. Now you meat,” before failing, and also getting murdered, just as Yoona gets murdered.

Much like Sonmi herself, Timothy Cavendish never set out to deliver a message of liberation, and yet he becomes the Moses to Sonmi’s Jesus, espousing concepts of the innate rights of humanity that only feel obvious and automatic to us because we’ve had the privilege to grow up in a society that allows us to learn about them. This is about as hopeful as Cloud Atlas gets, suggesting that even as we destroy our planet, kill and eat most of ourselves, and ultimately have to call for rescue from the rich tech bros who peaced out to the offworld colonies, that even if humanity forgets how to be decent to each other for a while, we’ll always reinvent the concept. Just like evolution keeps inventing crabs, humanity’s evolution, at least until we destroy ourselves for good, will keep producing both suffering and compassion. Cain and Abel. Yin and yang. Romulus and Remus. And anyone seeking to make assertions about which represents the most fundamental nature of humanity will find plenty of evidence to support their position.

Does this all sound a bit silly to you as I describe it? Truly, some of the stories openly invite derision and laughter, with Hanks, Broadbent, and occasionally Weaving collectively engaging in a competition of who can be the most ridiculous villain at one time or another. The entire far-future storyline uses a nearly incomprehensible pidgin version of English (if you know one thing only about Cloud Atlas, it’s the phrase, “that’s the true-true”), which is actually quite comprehensible if you pay attention and also never stop rewatching the movie as I have. And there is, of course, all the makeup, which I openly mocked even in 2012, referring to it as “intolerably bad”, and describing the ease with which I could spot a recurring cast member – even in minor, superfluous parts – by just keeping an eye out for the camera lingering on someone with a fucked-up face. We have white and Black actors playing Koreans (including lead Jim Sturgess playing 22nd Century Union Commander Hae-joo Chang), we have black and Korean actors playing whites, and we have some truly baffling choices (like Halle Berry playing an Indian woman in a cameo in 2012). There are broadly two questions to ask about this that I can personally relate to. The first is, “Does the overall effect work for me or not?” The answer to this is yes, but about as well as seeing Star Trek actors in facial prosthetics playing aliens with minor cosmetic nose and forehead differences. It feels theatrical, much like the ensemble casting overall, but it’s playing at a vague enough theme of recurrence and reincarnation that it can keep the significance of that recurrence nice and loose, with Luisa Rey (Berry) reading old letters from Rufus Sixsmith (played in two doomed, lovelorn ages by James D’Arcy) and pondering aloud why we keep making the same mistakes over and over again. And yet, I can imagine (and just watched a featurette which confirmed) that the directors and makeup crew must have pondered aloud, “Okay, we have nothing for [main actor] to do in this timeline – how can we fuck up their face and bring them into it?” Which is how we get Broadbent playing a street musician or Zhou playing a bellhop. Each of these oddball appearances (which clearly took a great deal of time and effort to produce) is a bit distracting individually, but as a whole, the entire effect feels like a drama department running around a stage, executing costume quickchanges and inviting their audience to use their imaginations and see the larger world they’re trying to create. In tonight’s show, the part of sleazy hotel clerk will be played by Tom Hanks, and it’s only his third-sleaziest character of the night, so get excited.

The second question is…is this okay? Is racebending okay? Is yellowface okay? Truthfully, I dismissed the quality of the makeup in 2012 because it was easier than engaging with this question in any serious or self-critical way. Can I recommend Breakfast at Tiffany’s as long as I caveat it by saying that Mr. Yunioshi (Mickey Rooney) is an atrocity against both Japanese people and cinema? Am I just being a typical see-no-evil white dude when I do this? I struggle with this question. And I have no definitive answer. Cloud Atlas contains an incredibly diverse cast, but all of its principal creators (including the Wachowskis, Tykwer, and book author and co-screenwriter David Mitchell) are white, as am I. When I’ve discussed this question with friends over the years, I’ve gotten no singular answer for how this aspect of the film makes them feel, and there is (of course) no singular answer to what Asian and Asian-American critics have to say about the film. It would be reductive and insulting to try to sum up the opinion of an entire multiracial cohort to how they feel being…impersonated? Caricatured? Made into a costume to serve some loose metaphysical purpose? If you’d like to see one critic’s biting take on this question, I’d recommend the inimitable Walter Chaw‘s two-star review of the film from 2012. But if you came here to hear mine, all I can do is admit my incapacity to answer this question. If I found the movie insulting or dilettantish when it came to issues of race, I wouldn’t like it as much as I do. But at the same time, I recognize that someone may be personally so bothered by actors playing characters of a different race, no matter what fantastical, theatrical framing is used for it, that they will not and cannot enjoy the film in any meaningful way. Or they may feel so accustomed to being made the butt of this particular joke in a white-dominant monoculture that the argument itself is exhausting for them (an argument I’ve personally heard as well). I can try to understand someone who feels this way. But I can’t feel what they feel.

Speaking of people I can’t exactly feel like, let’s talk about composer Robert Frobisher (Ben Wishaw), who begins his tenure as a disaster bi with a flight through the window from his lover Rufus Sixsmith (D’Arcy) after a romp in a hotel that’s threatening to call the police for their mere existence – a theme of presumed, systematic oppression that begins here as an artifact of a period piece taking place in an English era in which war hero and computing pioneer Alan Turing was chemically castrated for the crime of being gay, and which has become horrifically more relevant in the intervening years as the far-right has apparently made a strategic decision to brand the entire LGBTQ community as a band of pedophiles. Frobisher also announces that he’s alone and about to shoot himself with a Luger belonging to his boss Vivian Ayrs (Broadbent), and pronounces suicide an act of “tremendous courage”, which is the closest thing to a coherent message that we can wrest from the doomed love story and short, bright life of this emblem of the Bury Your Gays TVTropes page. And yet I love this story. I find it beautiful and deeply touching. I lap up every absurdist detail as Frobisher and Sixsmith smash up a china shop (in Sixsmith’s dream) as the former proclaims in voiceover that all boundaries are conventions, any of which may be transcended if one can first conceive of doing so. As this voiceover and music swells, the couple a few hundred years on in Neo Seoul just gets to have some regular hetero sex about it. As I wonder about what the Wachowskis – both trans, but one not quite as far along – could have been thinking here, the answer is once again…I can’t feel what they feel, nor can I presume they told this novel-adapted story in this way because it was something they personally found relatable. But as Frobisher skulks around the Scott Monument in Edinburgh, watching Sixsmith, a man he loves dearly but has already decided never to see again, climb those same stairs in a doomed effort to save his life after watching his final sunrise, I weep. Every time. Frobisher even told Sixsmith that he’d be there (a detail I only picked up in this viewing). All he needs to do is cry out, and he’ll get the embrace and solace that he so desperately needs. Sturgess and Bae get it, as Adam and Tilda Ewing, embracing each other desperately in the past as their souls could never manage permanently in the future. Hanks and Berry get it, finding their own better natures, and eventual friendship, duty, and even romance with each other as the dregs of humanity shamble into their next adventure. But the queer men get to be sad and stay sad and die about it. D’Arcy returns as an Archivist, and as much as I enjoyed the performance (and was taken out, as ever, by the weird-ass facial prosthetics), his mystified stare at Sonmi as she explains her ideology for the benefit of future Unanimity historians comes with a hefty dose of irony, as they’ll only have about 70 more years to discuss it before they annihilate themselves. It hardly feels like a fair ending for a character who has known nothing but pain in his lives and soul. Ditto Wishaw, whose happiest ending seems to be in a brief appearance as Georgette, managing to have a brief, offscreen affair with her brother-in-law, Timothy Cavendish, finally consummating the never-was romance between Wishaw and Broadbent’s previous characters in 1936.

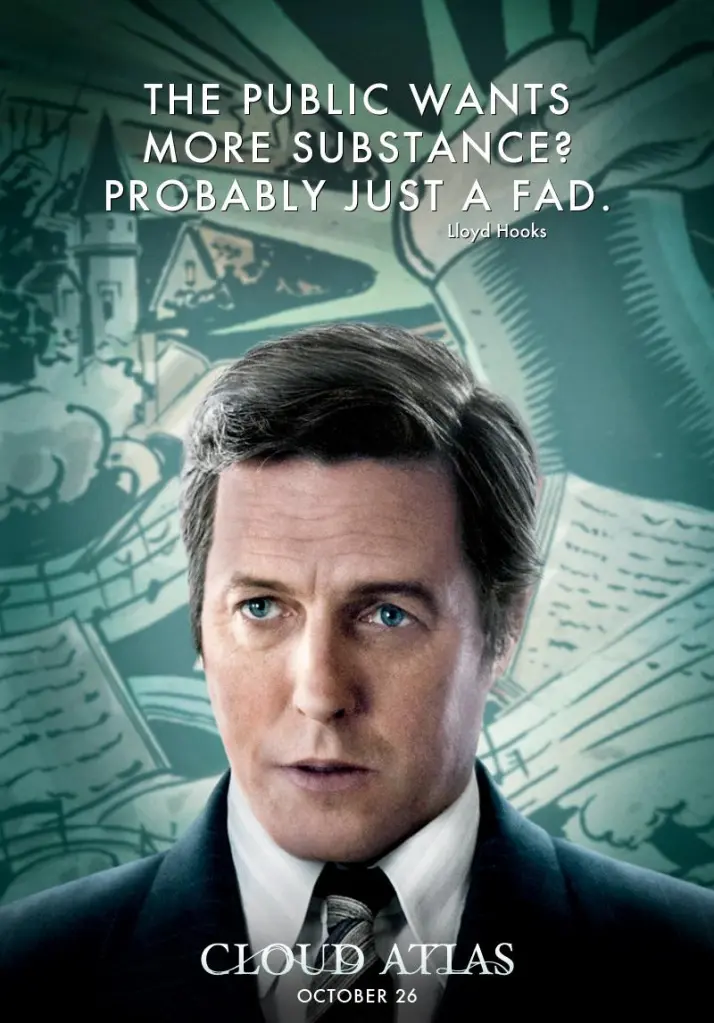

Attempting to plot a coherent path for the other actors as reincarnated souls is frankly a doomed enterprise. Keith David and David Gyasi begin as slaves and become commanders of the most dominant surviving and well-meaning faction of humanity. Susan Sarandon is and ever shall be, as much herself in each of these timelines as she was in The Banger Sisters. Which is fine. There are some actors I don’t prize for their range, and Sarandon is right there in a huddle with Dwayne Johnson, trading on bare charisma alone. Weaving begins as a slavery apologist and beneficiary and becomes…the literal devil. Grant – whom I haven’t discussed much outside of his performance as Cannibal Hugh Grant (one of the first and best things I mention about Cloud Atlas to anyone who hasn’t seen it) – is simply outstanding as an irredeemable piece of shit in every era he exists in, including as oil lobbyist and would-be nuclear saboteur Lloyd Hooks above, whose pronunciation of “Mssssss. Rey” somehow becomes more insufferable with each recitation, as does his ever-evolving American accent. Grant’s characters are sublimely vile, and the actor must have had an absolute hoot playing them. Yes, a bunch of them had star marks on them, just like the fabricants in Neo Seoul. And that means…something. But fundamentally, some of the reincarnations tell a coherent story, and others do not, and aren’t trying to. Editor Alexander Berner is the unsung hero of the show, because even as this film was making multiple simultaneous filming units and impromptu bits of casting and makeup happen, Berner was the wizard who got to stitch it all together, making a chase in one era continue to another. A bullet fired in one era fly past the shoulder of another. The editing is as fundamental to this film’s narrative and thematic coherence as the musical score, and Berner deserves every accolade he has received (including Saturn, OFCS, and Lola awards).

I could go on. I haven’t said much at all about the 1973 Luisa Rey mystery (a paranoid thriller whose plot bears an amusing resemblance to a 2005 Doctor Who episode), or about The Self-Serious and Self-Inflicted Ordeal of Timothy Cavendish in 2012, because if ever there were a pair of stories which do exactly what they say on the tin, it’s these two. And yet to the extent that these offer a zany tonal balance to the more serious storylines, I must also confirm these two stories – little more than goofy, pro forma genre exercises – still utterly riveted me. Broadbent plays up Cavendish’s self-dealing narcissism with such a total lack of self-awareness (I can see why he made such great casting for Horace Slughorn) that you can’t help but feel compassion for the character, even as he’s getting – and then getting away from – precisely what he deserves. As Luisa Rey’s neighbor kid Javier Gomez (Brody Nicholas Lee) – the author of a diegetic text summing up this timeline for any far-future readers – prods and then kicks through the fourth wall by telling her that she has just said exactly what a character in any decent mystery would say right before getting killed, you’ll roll your eyes. But then you’ll leave your balcony door unlocked so he doesn’t get stuck out there after jumping onto it after you asked him not to, because like any decent kid noticing a cliche for the first time, Javier fundamentally means well, and sincerely feels as if he’s invented something new. And so it goes with Sonmi herself, who spouts a stream-of-consciousness sermon worthy of a first-year philosophy student about what we owe to each other (The Good Place did this better), which nonetheless becomes humanity’s last great theology, elevating Sonmi herself to godhead status right before she gets crucified. Eternal recurrence.

One thing I have done in the last 10 years is read a lot more sci-fi. To name a few (in addition to Mitchell’s novels Cloud Atlas and The Bone Clocks), I’ve checked out Walter M. Miller Jr.‘s A Canticle for Liebowitz, a 1959 novel which examines cycles of future history as humanity destroys and renews itself in turns (a recommendation from FilmWonk Podcast co-host Daniel Koch, who hated Cloud Atlas then and ever since), and the only concept that feels dated in retrospect is when humanity invents a room-sized supercomputer whose sole function is translating languages. Cixin Liu‘s Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy begins as a tale of distant, nebulous alien invasion, and becomes a tale about humanity taking grand steps into the stars and merging with the fate of the entire universe. Margaret Atwood‘s Oryx and Crake begins with a narrator positing that humanity’s grand experiment with civilization is always one generation away from permanent extinction (and making it clear from the jump that this generational extinction has already happened), because we’ve already mined all of the near-surface metals that exist on Earth, and the technology to mine deeper ones cannot be rebuilt from scratch once it is lost. And N.K. Jemisin‘s Broken Earth trilogy, perhaps the bleakest of all, used similar cycles of destruction and renewal to seal humanity’s fate as not at all worth saving. Sci-fi/fantasy always exists somewhere on this spectrum, both making a guess or an exploration into possible futures, and inviting the reader to ponder how likely we are to experience them. Or to deserve to. Cloud Atlas still has a place in that line of grand ideas for me. Despite all of its peril, doom, and death, its slavery and cannibalism, and its wholesale, self-induced destruction of humanity, it is fundamentally a hopeful story about the power of love and humanity’s better nature. And it’s one I expect I’ll keep coming back to, if only because I still desperately wish to believe it’s true.

Or true-true.

FilmWonk rating: Still 9 out of 10, still my #1 of 2012, and still a masterpiece.