This review originally appeared as a guest post on 10 Years Ago: Films in Retrospective, a film site in which editor Marcus Gorman and various contributors revisit a movie on the week of its tenth anniversary. This retro review will be a bit more free-form, recappy, and profanity-laden than usual.

“I love you! You don’t understand – I’ve never said that to anyone before.”

-“You’ve never said ‘I love you’? “

“No!”

-“You never said it to your parents?”

“No.”

-“You never said it to your brother?”

“Ugh!”

-“Jesus, you’re more fucked up than I am. I once said it to a cat.”

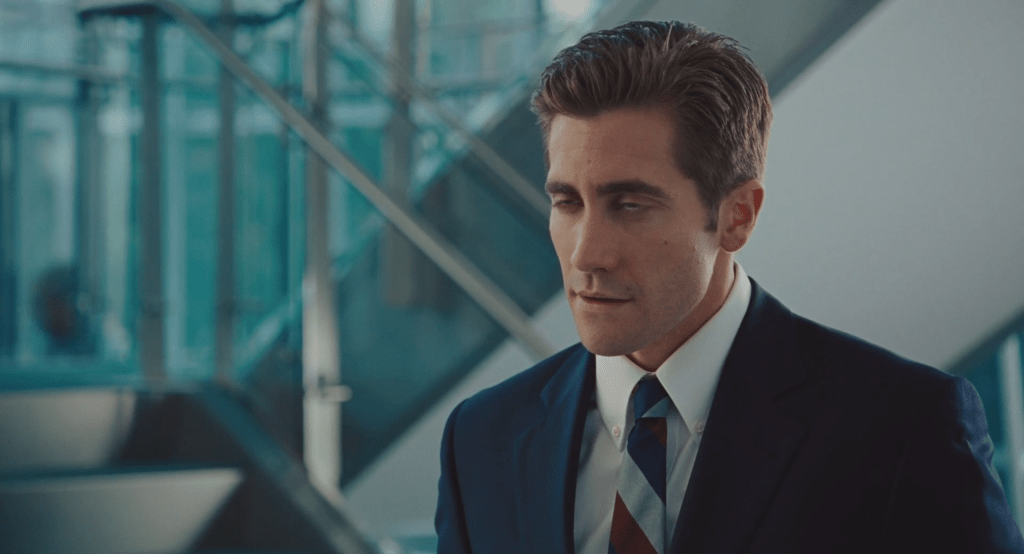

Flashback to 2010, as director Edward Zwick (Blood Diamond, The Siege, Glory), a director whose work I’ve tended to enjoy as it beats me about the head and face with its point, takes us on a tour of the alarmingly sexy and morally dubious world of 1990s pharmaceutical sales! We open on a montage in 1996 – “Two Princes” (Just Go Ahead Now) by the Spin Doctors plays, as we meet one Jamie Randall (Jake Gyllenhaal), effective and charming stereo salesman, who is highly successful at selling 1980s boomboxes by charming, flirting, and dancing with customers. Then he takes a quick five to have sex with the girlfriend of the store manager in the backroom, before she accidentally buttdials the manager on her Motorola Razr as he stands with customers on the showroom floor. At the place where all three of them work. Naturally, Jamie gets fired for gross, gross misconduct, but not before getting another girl’s number. Fifteen seconds post-coital, we learn that Jamie has chutzpah, and is, to put it mildly, a bit of a womanizer. This definitely feels like a ’90s period piece for at least the duration of this scene, but after that, the dialogue is pretty well peppered with modern references, including Jamie’s rich asshole brother Josh (Josh Gad), whose wife “looks at his dick like it’s the eye of Sauron”, and throws him out of the house because he’s addicted to internet pornography – an impressive accomplishment in ’96! Must’ve gotten an ISDN line installed for that. After a brief dinner in which Jamie’s rich asshole parents chide him for getting fired, Josh offers him his next gig, as a pharmaceutical sales rep for Pfizer, hawking Zoloft (a name-brand anti-depressant) and Zithromax (a name-brand antibiotic) by visiting doctors’ offices with swag and out-and-out bribes in order to gently encourage them to prescribe it to their patients. I already knew this profession existed – my mother did this job in the 90s before switching to insurance, and I can still remember all the swag she would keep around the house.

This is before another montage shows us that A) Pharma conventions in the 90s were gaudy as hell (think Tony Robbins meets WWE, plus the “Macarena“), and B) Pharma reps, also known as the “detail team”, were encouraged from the outset to push off-label usage of their drugs. It is at this point that I’ll mention, I chose to re-review this particular film because of my recent reading of Gerald Posner‘s excellent and exhaustive history of the pharmaceutical industry, Pharma, which I’d encourage everyone to check out (especially if you want to be nice and angry at what a softball deal Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family has just received after basically inventing a half-century of pharmaceutical advertising tricks, as well as the epidemic of Oxycontin and other opioid abuse). According to Posner, promoting off-label usage has not only always been routine in the industry, it is a core component of their business model. In fact, if you want to get even angrier, read up on how off-label usage combines with misuse of the so-called Orphan Drug Act to allow companies to maximize revenue while blocking out generics for an extra-long patent period, and jack up the prices, with their research heavily subsidized by taxpayers. Jolly fun! But that’s about as far into the Pharma book as I’ll be delving in this review, because apart from occasional barbs about America’s ridiculous healthcare system (which was even worse in the 90s), Love & Other Drugs really only uses pharma as a romantic backdrop, as well as a platform for dick jokes. Lots and lots of dick jokes.

So Jamie is a newly minted, slick-haired pharma rep, and also a big ol’ asshole, who reveals early in the film that he dabbles in pick-up artist bullshit, calling a hot girl by the wrong name (so that she’ll wander up and correct him, and he can reveal a backstory of thinking she’s a woman he rejected, which’ll make her want to get with him, and it honestly sounds so tedious as I’m describing it). This puts him in good company with Dr. Stan Knight (Hank Azaria), currently an avid Prozac prescriber, and apparently the most important internist and GP in Pittsburgh, who can somehow singlehandedly redirect every doctor and headshrinker in the City of Bridges toward Zoloft if only he switches his own patients off Prozac first. So Jamie straight-up bribes him with a $1,000 check from Pfizer to “shadow his practice” and give him the hard pitch all day. Dr. Knight responds with feigned moral outrage before pocketing the bribe, then uses the time to ignore Jamie’s pitch and ask for a bribe that’s several orders of magnitude larger, asking for a plum consulting gig in place of all the gifts and swag and beach conferences in Cancun that he’s apparently getting from Eli Lilly to promote Prozac. I knew this even before reading Pharma, but none of this, including the gaudy convention, is much of an exaggeration from reality. Despite Dr. Knight’s disinterest in switching meds, Jamie scams and seduces and petty-crimes his way into this clinic (with Judy Greer appearing as in one of her many, many devious and hypersexual secretary roles sandwiched between Arrested Development and Archer). This petty corruption and its outsized impact do succeed in making Pittburgh feel a bit small (we basically only see a single medical practice, adjacent back-alley, and nearby bar in the entire film) and consequently, the characters are constantly running into each other. But there are is an amusing gag here – a homeless man who keeps retrieving the Prozac samples after Jamie tosses them in the dumpster, and over the next few scenes, looks more and more respectable each time we see him, until we finally learn he has a job interview coming up! I didn’t mind this bout of silliness too much, since the butt of this joke is firmly the American mental healthcare system.

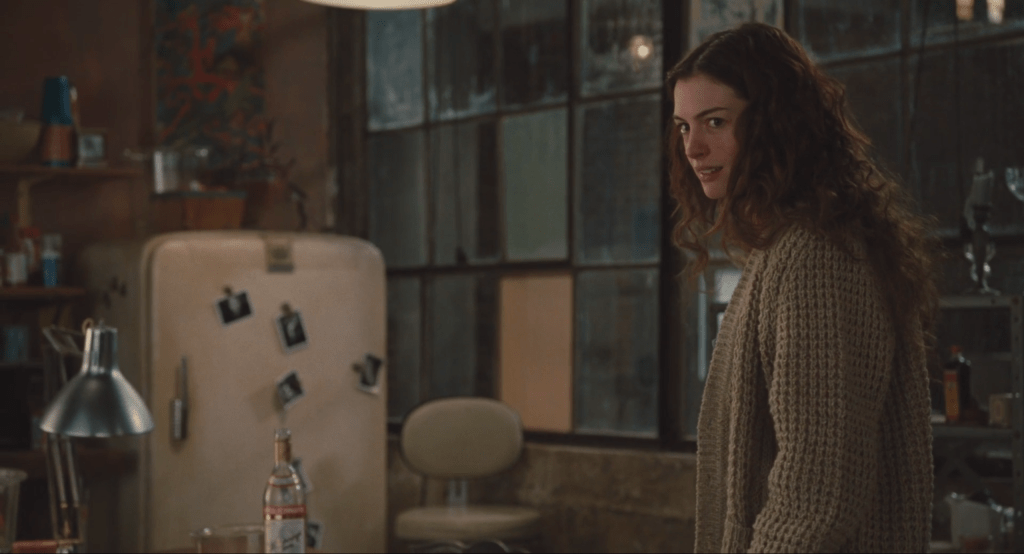

Jamie also reveals his predatory tendencies a bit more in this scene, as uninsured 26-year-old Parkinson’s patient Maggie Murdock (Anne Hathaway) concludes her exam (for a refill of her Parkinson’s meds) by asking Dr. Knight to examine a mark on her breast, which he does, as a lab-coated Jamie gawks. That Maggie discovers his true identity and savagely beats him in the parking lot with a briefcase in the very next scene is at least narratively redeeming – especially since this is a pattern that will continue as the film goes on: Jamie’s shallow bullshit delivered with utter confidence and charm, before getting smacked down hard by reality until he tries something a bit more sincere. But he doesn’t try that yet – instead, he delivers a charming apology on behalf of the entire medical community for treating Maggie in such a dehumanizing manner, which is, if you really think about it… Maggie silences him with several barbs, snaps a Wall ‘o’ Shame Polaroid, gives him the finger, and quits the scene. It would be very easy at this point to say that Jamie is doing the mercenary libertine schtick from Thank You for Smoking and Maggie is doing the quirky, wounded fawn from Garden State, and but there’s something a good deal more mature and substantial happening here. While these characters obviously start off at different levels of likability, they are essentially just two self-possessed grownups who don’t have time for [other people’s] bullshit, and are each fairly upfront about their visceral attraction to one another. Their coffeeshop date contains a lot of metatextual patter in which they allude to how the scene might play out if they were each playing their respective roles as expected, but then they jump straight to the booty call that they each really came there for. It somehow landed precisely on that line between contrivance and sincerity – when I saw this a decade ago, I probably regarded it as an attractive fantasy that the hot, interesting people were probably engaged in. In my 30s, my reaction is just…yeah, this happens. It may not be a guaranteed recipe for anything more than a quick bang, but I know more than a handful of people in serious, long-term relationships that started on such terms, and quite as many that did not, but who’ve enjoyed a shallow bang or six in their time with no regrets. It also definitely helps that the brief, quasi-animalistic sex scene that ensues is not layered with an overwrought musical track (now for sale on iTunes!), doesn’t contain dubious or disturbing implications with respect to consent, and simultaneously feels sexier and more grounded in reality than anything that appeared in any of the Fifty Shades films, which were as much an austere, sanitized fanfic about sex as they were about Twilight. And we’re only 30 minutes into the film when this thing, whatever it is, gets started. The couple untangles their mostly-clothed bodies on the floor, and Maggie tells Jamie politely to get the hell out of her apartment. Then she pages him to fuck in an alley, literally 10 seconds into the next montage. Despite their mutually-stated desire to keep things simple and distant, Jamie manages to spill a bit of expository pillow talk about how he was smart enough to get into med school, but didn’t want to give his dad the satisfaction, and Maggie manages to ask whether he’s ever said a true thing to a woman in his life. And they cuddle a bit. Progress!

Jamie goes back to the alley behind the only doctor’s office in Pittsburgh to toss out more of those pesky competing Prozac samples, only to catch a well-earned beating from Trey the Eli Lilly rep (Gabriel Macht), who is also both an ex-Marine and an ex of Maggie’s. Which is a genuinely bizarre and intriguing bit of backstory for Maggie’s character. I wasn’t quite sure how to classify Maggie besides…an experienced medical patient. But in a later scene, she flat-out calls herself a “drug slut”, and I found myself wondering whether being a pharma groupie is or has ever been…a thing? I’ve heard that Emergency Department nurses frequently end up dating cops, and it stands to reason there may be other professional romantic subcultures I may be unaware of. Before COVID, I joked more than once that the business travel market would collapse if not for the professional class’ insatiable need to get away from their spouses and children for a couple weeks a year to discretely bribe and fuck each other amid half-remembered keynotes and breakout sessions, and it fits this motif that Jamie gathers himself up and returns to Dr. Knight’s office (again!), only to get the cold shoulder from both of the receptionists (Judy Greer included), whom Trey has bribed with a convention/trip to Hawaii. The movie is…very unsubtle on this point, at one point showing Dr. Knight (who abuses Viagra samples later in the film) literally injecting himself with testosterone so he can attend a convention-adjacent orgy.

Jamie is naturally a bit bummed about these twin smackdowns, so he goes to see Maggie, who initially looks confused at his arrival with takeout. Structurally, now it’s her turn to be vulnerable and talk about her mother, before they both recoil away from it and remind each other they’re not quite a couple yet. Then they have some honest chitchat about her former affair with Trey the Eli Lilly Rep, who was and is married to someone else. Maggie gets a bit vulnerable here and admits she has a type, and Jamie very wisely gives her no grief for it. Now it’s time for more sex, but Jamie’s mind stays a bit unfocused and flaccid, and his penis follows suit. Maggie smiles and calls him a lying sack of shit with latent humanity (by way of accepting the situation and being kind about it), and they briefly, nakedly act as if they’re in an intimate relationship, eating cereal on the couch and talking about his day. She discusses the psychology of men and their capricious boners, and then lets slip that she read somewhere that Pfizer is developing a “fuck drug”. Hmmm… MDMA already existed in ’96 – and ironically can cause erectile dysfunction – so she must mean Viagra! A vasodilator with an accidentally lucrative side effect (discovered during clinical trials for pulmonary arterial hypertension), which would end up selling over $2 billion in prescriptions over the next decade. But enough about the history – I’m stepping on Hathaway’s superlative and scathing delivery on a rapid-fire series of dick puns as I type this, which finally gets Jamie going again. And for the rest of the movie (after a softball pitch to his boss), Jamie will indeed be selling Viagra, because, as he puts it with that unassailable Gyllenhaal charm, “Who can sell a dick-drug better than me?”

Over breakfast the next morning, Maggie has a hand tremor and can’t open a Pop Tart for Jamie. She covers for it, handing him the package, sending him out the door, and asking him not to call again, because she can’t do…this. This being a relationship, which she feels she doesn’t want, can’t handle, doesn’t deserve, shouldn’t inflict upon him, etc. Obviously, it only takes one more scene of [inexplicably pharma-tinged] rom-com theatricality before they decide to give the whole relationship thing a try anyway. It involves a busload of seniors trekking north of the border for meds they can’t afford in the US, an operation that Maggie is either a volunteer or participant for. Jamie endears himself to her by…showing up as the bus leaves, and then waiting all night until it returns, and okay sure, I guess. Love & Other Drugs offers a working definition of a relationship as a constant defining, prodding, communicating, and redefining of both internal and external boundaries to gradually coalesce around each other. In the usual rom-com fashion, much of what Jamie does meets the legal definition of stalking (and he conspires with her doctor’s office to commit multiple HIPAA violations!), and at first, it’s pretty clear that this is just one more dubious conquest for him. Until it isn’t. Then, after their nth hookup, Jamie casually refers to Maggie as his girlfriend, and she realizes she’s okay with that. Then he straight-up has a panic attack when he realizes (and states aloud) that he loves her. It gets worse from there – she has a bad day with her illness, which turns into a bad, drunk, insecure, borderline abusive moment, in which she caps off an unhinged rant by flat-out telling Jamie he’s not a good person just because he “pity-fucked the sick girl”. Then she drops and shatters her vodka glass and bawls onto the floor as Jamie is storming off, but…he comes back to comfort her. This seems thing-adjacent to the typical ebb and flow of a burgeoning romance, so it’s worth taking a step back to discuss this film’s treatment of disease, disability, and mortality.

I’ve seen a number of films in which creatives who aren’t dying or disabled make an effort to get into the headspace of people who are (there is also a healthy discussion around what disabilities it is appropriate for non-disabled actors to depict). Maggie’s illness is largely discussed as an inexorably fatal one, which is not exactly false (people with Parkinson’s do have, on average, reduced lifespans compared to people who don’t), but it’s not exactly true either (early-onset Parkinson’s cases tend to have many years ahead of them). In fact, for a film that’s clearly trying to drop a few real facts about the disease, it somehow elided a detail that I didn’t know until I looked it up after the film: Parkinson’s is not a fatal disease! It is a complex and not terribly well-understood disease (mostly as true now as it was in 2010), but people don’t die from it directly. They die from complications caused by it, such as falls, infections from injuries, aspiration pneumonia (due to swallowing difficulties or feeding tubes), etc.. This may seem like a semantic distinction, but it’s important to consider when viewed in the context of Jamie and Maggie’s respective dysfunctions about it. Jamie and Maggie’s relationship is generally pretty relatable, even if it seesaws back and forth a bit more than a conventional rom-com. The film seems to generally treat Maggie like anyone else who feels she’s undeserving of, or doesn’t have time for, love, perhaps because of her romantic history, or other concerns in her life, or both. Her Parkinson’s, therefore, feels less like an intrinsic component of her identity than an obstacle the film completely forgets about during the extended fuck-montages and bits of interstitial cringe comedy (including every single appearance by Gad’s wholly excisable brother character), and then remembers when it needs to reach for a moment of romantic pathos.

After their drag-out fight and reconciliation, Jamie and Maggie head to Chicago for a pharma convention. Maggie is spotted in short order by another Parkinson’s patient who tells her the real party is across the street, so she excuses herself to the event, which calls itself the “Unconvention”. I thought perhaps the film was going in a weird, alternative-medicine direction at this point, but this was pretty clearly a community support group, featuring a number of real-life Parkinson’s patients. A comedian on-stage (played by Lucy Roucis, who has kept up her craft on the Denver theatre stage in the intervening years!) is doing a bit of disease-themed standup. She’s interspersed with various others, some of whom are clearly untrained actors, hollering out a cathartic series of “fuck [whatever]” type statements for things in their life that annoy them because of their condition – shirt buttons, coffee mugs, soup, etc. A woman in her 50s steps up with a cane and ponders aloud why God wanted Parkinson’s patients to be so good at giving handjobs. And so forth. It’s all very sweet and funny, and a bouquet of emotions flies across Hathaway’s face as we silently learn that Maggie has never seen anything like this, and finds it all terribly moving. And why not? She gets to see variety of people, all different ages, disease stages, and body types, speaking their truth onstage and think that maybe, just maybe, there’ll be a world where she doesn’t have to go through this thing alone. Jamie shows up toward the end, just in time for a man at the coffee bar (who is there with his wife, a Stage 4 Parkinson’s patient), to initially refuse to give him any advice, but when pressed, to admit that he loves his wife, but that his life as a caregiver wasn’t worth it, and he wouldn’t do it again. In fact, he goes further: he flat-out says that Jamie should dump Maggie and find himself a healthy woman. I’ve met multiple older folks who have succumbed to some degree of caregiver fatigue after a long life of looking after a sick partner or family member, and for this film to pretend like everything is hunky-dory for the families of all these people standing up onstage and enjoying community time together would’ve made the whole event seem contrived and insincere. I found this man’s attitude very sad, but I found it to be an honest and relatable narrative choice. I hope he was just having a bad day, and that he has time and people to look after himself as well. But for him to express this attitude aloud illustrates the very real peril that the caregivers of a Parkinson’s patient are in (which in turn places the patient themselves in similar peril). Burnout is a real thing, and kudos to the film for neither overstating it nor shying away from it.

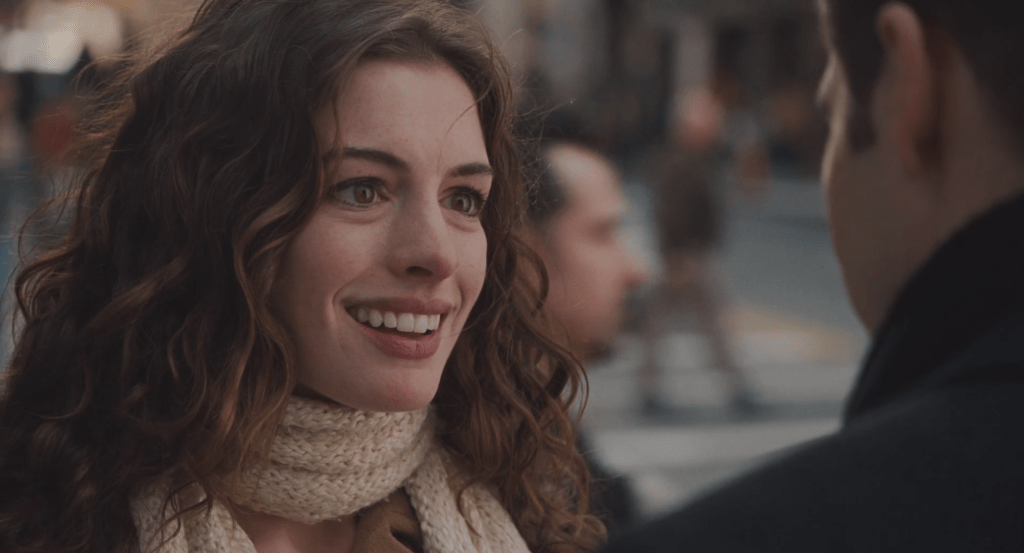

Jamie doesn’t really react to this, because Maggie ushers him out to apologize in the street for the vodka-soaked tirade in the previous scene and say that she loves him. This is a curious repetition of how Jamie came to realize that he loved her – by interacting with other people who weren’t her. This is admittedly still rather sweet, largely because of the actors’ chemistry, but it was also the part of this rom-com that I perhaps found the least relatable. Coming to say “I love you” is something I strongly associate with spending time with the person I love. Finding that feeling through separation seems to be a rom-com trope, but to me, it has always suggested that what these people really love is life itself, or perhaps themselves – and they just felt the need to run home and tell it to their partner. I’m not sure if this makes movie love feel less than the real thing, or if it’s simply narrative shorthand that I can excuse, but my receptivity to it will largely depend on how much I believe the actors when they say the words. The other mirror image going on here is that neither of these two is sure whether anyone else deserves the affliction of being in a relationship with them – Maggie because of her illness, and Jamie because he has spent far too much of his life trying to be an asshole. It’s pretty easy to say Maggie deserves whatever happiness she can grab onto, but what of Jamie? Does he “deserve happiness”? I would say that deserve is not a meaningful framework here. No matter how many bad things a person has done, the only person who can practically deny them happiness is the person himself, and perhaps anyone they think they love. From a purely utilitarian standpoint, discounting any belief in karma or a fair and just world, I think it’s appropriate to say the world is better off if people like Jamie are happy, because then the world won’t have to deal with his toxic bullshit quite so much – and perhaps neither will his partner. His happiness has the potential to make the world a better place. As for whether Maggie deserves happiness, she obviously does – she’s a kind, intelligent, and creative person who has a lot to offer a potential romantic partner. But there is a similarly brutal utilitarianism that applies to her situation. The idea of Maggie thinking of herself in these terms – as someone that neither the world, nor the people she loves, should have to make the effort to help – felt completely human and sincere, but also made me very sad. As did what happens next.

Jamie gets to work with all of his powers as a pharmaceutical rep who knows Philly’s biggest sexpot physician to try to cure what ails his girlfriend. I’m sure he’ll sort it out, right? He hits up Dr. Knight for contacts for all the cutting-edge, experimental Parkinson’s treatments, and we enter a montage of him dragging Jamie from one medical provider to another trying to order up one (1) Parkinson’s Cure, please! Minus the please. There’s an extended sequence where he harangues a receptionist at Massachusetts General, telling her they flew 2,000 miles (from Pittsburgh – not the first time he has used this weirdly specific numerical lie in this film), only to find out their appointment has been postponed two weeks without notice, then starts Karening out all over her, demanding to see the doctor (who’s not there), the head of the hospital (who doesn’t care), etc., as Maggie sits in the foreground looking more and more mortified before finally getting up to leave. They argue in the snowy parking lot, and she tries to give him a way out here – says she’s bored, and tired, and wants to go home – before he asks her whether she wants to get better, and…that’s it. Maggie realizes that this impossible thing, a cure for her Parkinson’s, has become much too important to Jamie, and tells him they need to go home, make some goodbye love, and then he needs to get his stuff out of her apartment, because they’re breaking up now. Because, as Maggie puts it, Jamie is such a good man he doesn’t want to be the one to walk away, so she’s doing it for him. This doesn’t feel like sarcasm on her part so much as mutually assured destruction. She really does think he’s a good man, but also a weak one. She doesn’t want to inflict herself upon him, but she knows he would allow it…if only he could spend the rest of his life trying to find a cure that doesn’t exist. It’s fraught. And her choice to dump him feels neither arbitrary nor unwise, even if it may not be her only choice.

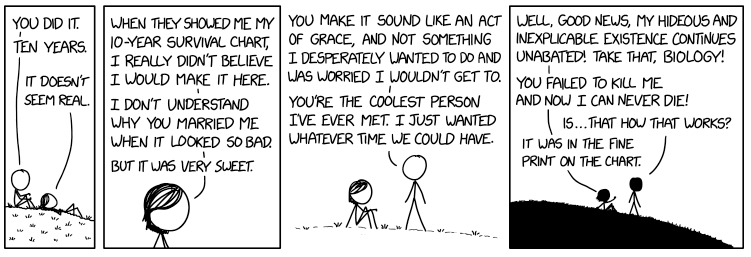

Excerpt from xkcd webcomic, “Ten Years“. Comic artist Randall Munroe’s wife recovered from a serious case of breast cancer while in her 20s. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License, almost the same one I use!

Excerpt from xkcd webcomic, “Ten Years“. Comic artist Randall Munroe’s wife recovered from a serious case of breast cancer while in her 20s. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License, almost the same one I use!

Like I said, Maggie makes me very sad. This is obviously a breakup that will reverse itself before the end of the film (if you’ve never seen a rom-com before, I apologize for the spoiler, but I won’t mention the sex-mansion pajama-party breakup-threesome Viagra-mishap!), but even their return to romance feels like a rather dour ending, because this feels like the origin story for the bitter old man at the “Unconvention”. Jamie will stay with Maggie, and spend every waking moment for the next 30 years trying to cure her (a terminal voiceover informs us that he’s thinking of applying to medical school!), before telling a young man in his former position that it wasn’t worth it. And Maggie will let him stay, but she’ll always feel like she’s imposing on him, and will occasionally chase him off for it. In that sense, the movie doesn’t really feel like it even has an ending, so much as it hits the predetermined beats of a rom-com in a story that can’t really mesh with them. This ebb and flow will continue, hopefully for the rest of their lives? Perhaps that was the filmmakers’ intent, but it left me giving this movie some credit for swinging high and missing rather than for telling a complete story. And Love & Other Drugs did swing high. It reflected on the interplay between romantic love and mortality as it relates to the human condition, and its treatment of disability felt neither tokenistic nor disrespectful. And for a film in which every dude is an irredeemable asshole, that counts for a great deal. There is nothing revolutionary about the idea that people who with reduced life expectancies have value and deserve love for whatever time they have, nor is there any separation between them and the rest of us. Maggie may know that her CNS function is on a path to deterioration, but Jamie could still be hit by a bus tomorrow. And for that matter, so could Maggie. Or they might live on. The most horrifying adventure of all.

FilmWonk rating: 7 out of 10