The first thirty minutes of Christopher Nolan‘s Interstellar are downright oppressive. They depict an earth saturated in dust storms and failing corn crops, struggling against agricultural blight to feed a starving and dwindling population. And the film conveys all of the details of this new reality with some unsubtle, but effective touches, including a school curriculum that now teaches that the Apollo program was merely a brilliant hoax perpetrated by 20th century propagandists in order to bankrupt the Soviet Union with futile dreams of progress beyond the stars. My only depressing note of incredulity at this detail was that even in our real-life, present-day world, with all of its vast resources and promise, we can already conjure plenty of excuses not to extend mankind’s reach into space – it’s hard to imagine that such propaganda would be necessary in a world in such dire straits. As a stark contrast to most other end-of-the-world disaster films, mankind soldiers on, but purely to maintain the status quo for just a bit longer. There is no Bruce Willis wrangling to save the world by nuking something – at least as far as the public is concerned. The remaining population is an agrarian “caretaker generation” – a designation that this film unambiguously condemns. Proverbial deck-chair wranglers on the Titanic.

This necessary, claustrophobic environment is broken up when astronauts Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), Amelia Brand (Anne Hathaway), Doyle (Wes Bentley) and Romilly (David Gyasi) leave Earth aboard the starship Endurance in a last-ditch attempt to save the human race. Their trip is designated “Plan B” in two ways – first, a series of previous missions have already been sent to find habitable planets, and the Endurance has been sent to find any survivors. And second, because Professor Brand (Michael Caine), a NASA scientist (and Amelia’s father), believes he can crack an equation that will allow the human race to conquer gravity – a necessary hurdle in order to evacuate the remaining population and enough materiel to support them. Structurally, this film closely resembles Danny Boyle‘s Sunshine, and in many ways, the characterization and interpersonal dynamics are inferior in comparison. Once the mission begins, Brand, Doyle, and Romilly are pretty ill-defined presences, and at one point, the crew engages in an important – but surprisingly puerile – debate over which potentially habitable world the ship should head for, made so by the out-of-nowhere revelation that Brand is in love with one of the previous astronauts, Dr. Edmund, who may still be alive on his planet. Edmund never feels like much more than an off-screen instrument for generating conflict, and it leads to Hathaway delivering a preposterous speech about love potentially being a force that transcends space-time. Transcending space-time is a rather crucial concept as the film goes on, and to introduce it in such a clunky manner nearly derailed it. And despite any dramatic irony eventually provoked by Brand’s speech, the concept never feels earned or justifiable, and did some serious damage to the character’s credibility in the process.

Nonetheless, the various “alternate Earths” are a real sci-fi treat. While they don’t stray too far from the Star Wars/Avatar convention of a single, vast ecosystem per planet, they incorporate several details that are both visually and conceptually stunning. One planet is so close to an adjacent black hole that time dilation becomes a factor, and each hour spent on its surface will translate to seven years passing back on Earth. Given the stakes involved for these characters, both at the personal level and for the entire human race, the film makes superlative use of this concept. Where the Nolans’ temporal manipulations in Inception served only to heighten the physical action, they serve in a similar way to heighten the emotional action in Interstellar, forcing its characters to feel the weight of years in an instant, and McConaughey’s performance particularly shines in this moment.

Back on Earth, Cooper’s daughter Murph (played as a child by Mackenzie Foy, and as an adult by Jessica Chastain) weighs the impact of years upon herself, as she is forced to deal with the unresolved conflict she and her father began when she was just 10 years old. Is Cooper coming back? Did he ever intend to? And regardless of his intent, is there any hope of him coming back? Much of the film’s plot hinges on her collaboration with Professor Brand on “Plan A”, to crack the theory of gravity so the remaining people can evacuate the earth – and the continuing influence of Cooper’s childhood betrayal hangs over the film throughout. More on this below.

Interstellar is, in many ways, one of the most ambitious sci-fi films ever made, containing all the style and visual splendor of sillier films like Prometheus, but with a substantially smarter script and some convincing exploration of the big ideas of sci-fi to back it up. A better comparison is 2001: A Space Odyssey, from which it takes a few obvious visual and thematic cues. Its use of practical effects and models provides a great sense of realism to the scenes set in space, from the rotating ring ship to a magnificent column-based robot named TARS (voice of Bill Irwin), whose “humor setting” allows him to land one of the film’s best zingers during take-off. The film never quite transcends its reliance on characters that aren’t nearly as well-drawn as the actors playing them, but it is still a must-see space opera for the 21st century.

***

Spoiler warning from this point on.

***

So what, then, do we make of the third-act appearance of Matt Damon as haggard, solitary astronaut Dr. Mann – the architect (and apparently sole survivor) of the previous missions? Like a similar third-act revelation in Sunshine, Dr. Mann is more concept than character, although Damon successfully imbues him with some complex psychology in a short space of time. If each of the astronauts is a sacrificial lamb for mankind, Dr. Mann is surely Judas, derailing and misdirecting the mission in order to save his own skin. He opted into a life of selflessness, but then found himself unable to follow through on it. Shame on him, for he is us – his name is even “Mann” (*sigh*). As much I enjoyed Damon’s brief performance, this is some pretty weak material, and ends far too quickly to have as much of an impact as the film’s five-dimensional mind-fuck of an ending.

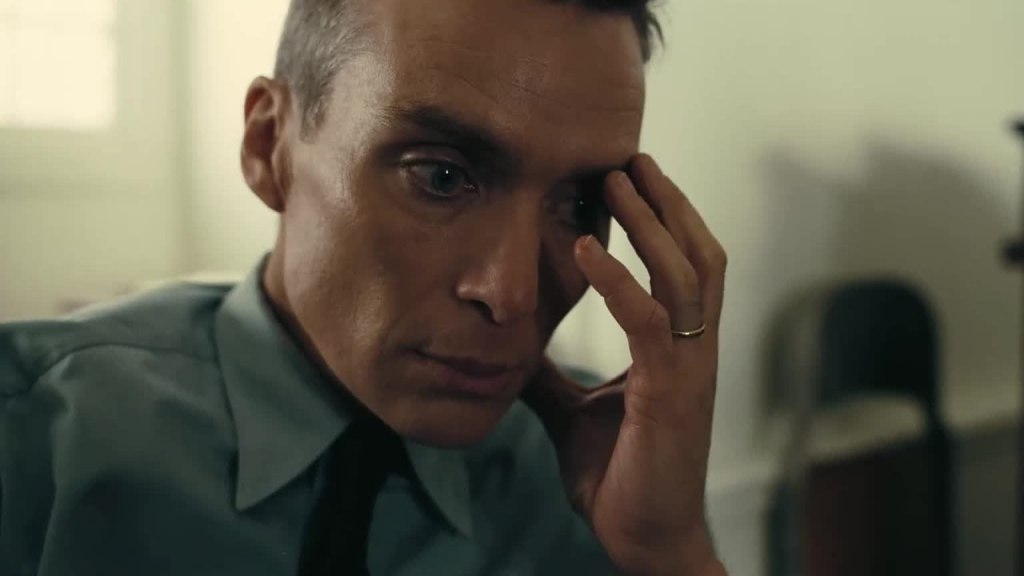

Indeed, there is a multi-layered, Terminator-style “future creates the past” temporal paradox at work here. Future-humans save their predecessors from extinction by creating the singularity and a reality for Cooper to interact with, and future-Cooper ensures that past-Cooper will end up exactly where he is – in an indescribably beautiful nether-space – a five-dimensional reality rendered in three dimensions, conceptually explained earlier in the film, when astronaut Brand speculates that fifth-dimensional beings might be able to descend a canyon to visit the past, or climb a mountain to visit the future. There are a few curious details here. There’s the obvious question of why the future-humans can’t simply explain their plan to Cooper (perhaps transcendent fifth-dimensional beings no longer speak 21st century American English), but I actually found it more fascinating that Cooper’s first inclination is to try to change the past and prevent his younger self from leaving his daughter back on Earth in the first place. It’s unclear if he is doing this because the mission has gone so thoroughly awry, or if, like Dr. Mann, he has simply lost all will to continue, and will do anything to undo his mistakes, even at the cost of all mankind. McConaughey plays with this ambiguity nicely, even as Cooper quickly realizes this is futile, and instead switches tactics to making sure that the past proceeds exactly as it did. He gives young Murph the location of the the NASA remnant, setting the film’s events in motion in the first place. Yeah, I didn’t mention the “gravity ghost” earlier – sue me. Pretty hard to discuss it without spoilery context. This becomes a predestination paradox – the fifth-dimensional reality allows Cooper to view and influence the past, but he doesn’t seem to be able to change events substantially except to nudge them into proceeding exactly as they did the first time. As the sequence goes on, it’s fascinating to ponder what would have happened if Cooper had simply done nothing upon entering the nether-space. Did he even have that choice? Would he have simply floated there forever?

The film also ends with a grand sense of possibility – and a big question – what became of Brand? When Cooper is rescued aboard “Cooper Station”, a vast cylindrical habitat that was constructed, launched, and sent to the edge of the singularity in the ensuing 60 years since Cooper’s disappearance (thanks, time dilation!), his daughter (now played by Ellen Burstyn) sends him away from her deathbed (and many children and grandchildren) to head through the wormhole and find Brand, who is surely waiting for him. The cheeriest possible read on this ending – which I daresay is supported by dialogue from the film – is that Cooper and Brand were in the time dilation field around the black hole for exactly the same amount of relative time, causing another 60 years to pass on Earth while the same (smaller) amount of time passed for each of them. Cooper took his timeline-altering dive into the singularity – and Brand landed on Edmund’s planet – at exactly the same point in history relative to Earth. And inside the singularity, Cooper existed outside of space and time, so he emerged without any additional time passing.

I’m laying all of this out for two reasons. First, because I suspect that many will regard Interstellar‘s final ambiguity with the same kind of Nolan-induced side-eye as Inception‘s spinning top, prompting endless debate and nerd-rage, and I’m eager to get my own interpretation on the record now. But the second reason is because it is only such a smart and well-drawn piece of sci-fi that can invite this kind of reflection. Interstellar may make a few missteps on the human side, but it is a smart, timely, and internally consistent space opera. And it’s absolutely gorgeous on film.

Spoilers over.

FilmWonk rating: 7.5 out of 10