This review originally appeared as a guest post on 10 Years Ago: Films in Retrospective, a film site in which editor Marcus Gorman and various contributors revisit a movie on the week of its tenth anniversary. This retro review will be a bit more free-form, recappy, and profanity-laden than usual.

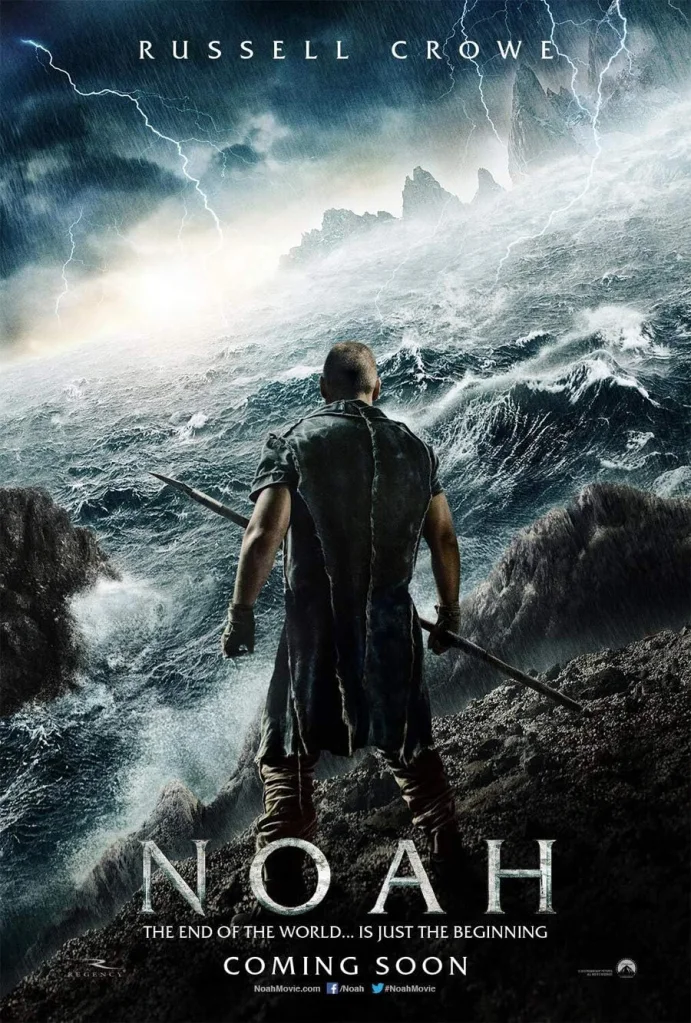

“But they ate from the forbidden fruit. Their innocence was extinguished. And so for the ten generations since Adam, sin has walked within us. Brother against brother, nation against nation, Man against Creation. We murdered each other. We broke the world, we did this. Man did this. Everything that was beautiful, everything that was good, we shattered. Now, it begins again. Air, water, earth, plant, fish, bird and beast. Paradise returns. But this time there will be no men. If we were to enter the garden, we would only ruin it again. No, the Creator has judged us. Mankind must end.”

–Noah (Russell Crowe) tells his family a nice little bedtime story.

I’m going to toss out a hot take this Easter week and say that Noah’s Ark has a better claim to being the greatest story ever told than the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. That was the first thing I wrote in my notes for my re-review of Darren Aronofsky‘s 2014 film Noah, right before an all-caps reminder to myself: “DON’T BE AN INSUFFERABLE ATHEISTIC EDGELORD PRICK”. I sincerely wish to comply with that, but I’m certain some readers will see this comparison and think that I’m belittling the sweetness and mercy of my man J.C. in favor of his crotchety Old Testament Forebear, less likely to bequeath the Earth to the meek than obliterate them with fire and brimstone. I’m not praising or condemning that version of God (as if He’d care about my opinion anyway), but I sure do applaud that notion – as well as its encapsulation within the apocalyptic tale of Noah (Russell Crowe) and the Ark – for its sheer popularity among humans. The Genesis flood, which parallels other deluge narratives that exist around the world, all basically fit the mold of a rebirth of humanity, following punishment by one or more deities for their sins and excess. It has been used to justify some genuinely silly beliefs, such as George McCready Price‘s 1923 book, The New Geology, a 20th century repackaging of a fringe idea from a century earlier, which states that every piece of evidence that exists of an Earth that is older than 6,000 years can be attributed to the Great Flood of Genesis, which in addition to wiping out all of humanity, carved out every geological feature that we might erroneously conclude takes millions or even billions of years to form, and spread out a nice, orderly, stratified fossil record filled with naught but the Devil’s lies (which coincidentally possess the expected ratios of uranium, thorium, and lead). I’m trying to front-load all of my scoffery for the Young Earth Creationists, who deserve quite as little intellectual consideration as they give their own ideas, because I’m well aware that most religious people don’t really think that they live on a tapestry of pointless, Luciferian deceptions, but rather think that the universe can be whatever way we observe it to be, but that does not preclude the existence of a loving deity who set the whole thing in motion, because they find this idea appealing, as well as a theoretical source of virtue and moral truth. And this is fine by me, really, as a baseline idea. I had my first child shortly after this version of the Noah tale came out, and while I haven’t yet sent him to Sunday School to peer at the cartoon Ark with its cartoon elephants and giraffes sticking out with giant smiles beneath sun and rainbow, I have had to explain life and death to him, and in so doing, I’ve had to grapple with my own conviction that religious faith and tales about mortality are fundamental components of the human condition, and one way or another, my children will be exposed to both and have to decide for themselves which stories they find the most comforting. And, depending on where they land, they’ll have to try not to be insufferable, atheistic, edgelord pricks about everyone else’s comforting beliefs.

The life and times of Jesus Christ are certainly popular, but they cannot be the greatest story ever told, if only because its adherents spend so much time ignoring or preposterously reframing them. Noah’s Ark, conversely, is a tale that humans have stood by through thick and thin because of its versatility as a tool of oppression and judgment. Humans, unique among apes for our perceptions of mortality and space-time, craft a uniquely human narrative: Do what I say or be judged wicked and face the wrath and apocalyptic vengeance of my god. The Curse of Ham (which does get a token nod near the end of the film) doesn’t even require any actual sins – it’s been used for the last thousand years to justify everything from medieval serfdom to the African slave trade, all on the grounds that some people are just born inferior because Ham (Logan Lerman) glimpsed his father’s drunken junk that one time.

The only specific sins called out in the Genesis narrative are violence and angel-fucking, and Aronofsky cleverly turns this in an environmentalist direction, crafting a version of barren Biblical landscape steeped in metaphor that hits hard in the modern age – a fallen wasteland dotted with distant, dying industrial cities, ancient technology, magical energy-carrying minerals, and a race of fallen angels called Watchers, rendered as beings of light trapped in the muck as huge, formless rock monsters, serving alternately as helpers and slaves of humanity, doing violence and hard labor alike in service to their will. This is Lord of the Rings meets Mad Max, with everyone in this land acknowledging the existence of the Creator like a fact they all accept in living memory, but with each interpreting it differently depending on their own inclinations and desires – just like most of the modern humans watching this version of this tale today. The descendants of Cain – the cursed, wandering son of Adam and Eve and the first murderer – have mined the Tzohar, built the cities, scorched the landscape, killed each other over resources, and hunted and eaten the animals. Aronofsky takes a few other creative liberties with Noah and his family, taking the biblical narrative that they are the descendants of Seth, but adding in that they are vegetarians in tune with the land who won’t even pick an errant flower if they don’t have some use for it. As one might expect, there were a few Christian biblical scholars and barbecue enthusiasts who felt the need to scoff at this notion when the film came out – and in all fairness, I did re-read the Genesis account for the first time since I was a child before rewatching this film, and it’s pretty clear that Aronofsky tossed out the parts of the story that didn’t fit his environmentally friendly message, including Genesis 9:3-5, which explicitly states that humans have a green light to kill and eat any animal that walks the Earth, provided they drain its blood first. Granted, the very next verse also contains an admonition not to kill other humans, and we all know how studiously humans have obeyed that one over the millennia.

This version of Noah (Russell Crowe) is as much of a patriarchal cipher as the one in the holy books, being virtuous because he is deemed so by the Creator, and knowing best because he is the man in charge of family and boat-making operation alike. And it’s hard to argue with that designation when reality itself seems to bend to his hallucinatory visions, making a forest spring forth spontaneously from nothing but a seed from Eden, a clever hand-me-down from Puckish man-of-the-mountain Methuselah (Anthony Hopkins), who is old enough (to his grandson Noah’s mere 600 years) to know that men of the Pentateuch can make miracles happen with nothing but their trusty thumbs and the confidence of a dude who speaks supernatural subtext aloud. It is with this miracle-thumb that Methuselah sets the third act in motion, curing the infertility of Ila (Emma Watson), an orphaned girl whom Noah finds as a child and raises as his own daughter. As she becomes a love interest for Noah’s eldest son Shem (Douglas Booth), the tension between her doomed desire to bear children for the boy she loves and Noah’s conviction that humanity has been judged guilty and must all die after saving the animals, becomes tension over whether Noah will slay whatever newborn child that his daughter should produce aboard the Ark. When I saw the film in theaters a decade ago, I daresay this act is when I checked out the most – acts 1 and 2, which consist of antediluvian Ark-building and angelic warfare with the wicked hoards of Tubal-cain (Ray Winstone), were absolute bangers. And then, following the Doom of Man, comes a schism within this family, as Noah’s wife Naameh (Jennifer Connelly) – a woman-shaped instrument like so many in the ancient and modern writings of men – acts as conscience and voice of mercy to Noah’s commitment to baby-murder, and his son Ham bitterly bonds with a stowaway Tubal-cain, who acts as the devil on his shoulder, trying to manipulate and corrupt whatever remains of humanity, because…why not? Nothing else to do in Waterworld. This isn’t the first or the last time that Aronofsky’s strained, secondary Garden of Eden metaphor would fail to fully land with me (hi mother!), but to my great surprise, I found myself sympathizing more with Noah this time around, if only because his dilemma actually seems to make some rational sense in this world. His God is definitely real, and has definitely just obliterated nearly all of humanity, and Noah has definitely been put in charge of deciding whether any humans get to live after that’s over with. Let’s set aside the question of whether any God-handwavey solution to this genetic bottleneck amounts to an admission that the entire Ark project was unnecessary anyway (I said don’t be an insufferable atheistic edgelord prick, Glenn!), and let’s embrace the Chosen One narrative that sees its prototypical form here. Here is Noah, Champion of God, placed in the position of having to decide whether his family, whom he loves and knows to be virtuous and good as he has taught them to be, should live or die.

If nothing else, this sequence was a stark reminder of the tantalizing nature of fanaticism, main character syndrome, whatever you want to call it. Noah is the main character, he was right about everything, and he holds the power of life and death over all of humanity because that’s what the story says: the great, megalomaniacal tale of the human race. The greatest story ever told. And the question of what to do with that power – whether to believe in a future in which humanity can be at peace with one another and in balance with their environment – is the fundamental question of the human condition. Do we sapient apes choose life, and hope, and a future for ourselves? Or do we let it all get swept away, taking meager solace in the notion that something will live on, and perhaps even become smart enough to ask these questions again, as we, God’s greatest mistake, return to the dust whence we came?

I don’t have an answer. But in the fullness of time, I’m sure we’ll come up with one together.

FilmWonk rating: 7.5 out of 10