This review originally appeared as a guest post on 10 Years Ago: Films in Retrospective, a film site in which editor Marcus Gorman and various contributors revisit a movie on the week of its tenth anniversary. This retro review will be a bit more free-form, recappy, and profanity-laden than usual.

“The oracle isn’t where the power is, anyway. The power’s always been with the priests, even if they had to invent the oracle.”

-“You guys are nodding like you actually know what the hell he’s talking about.”

“Well, come on, Chief. The way we work, changing destiny and all – I mean, we’re more like clergy than cops.”

-Dialogue from Minority Report (dir. Steven Spielberg, 2002)

Rick: “What — What’s this supposed to accomplish? We have infinite grandkids. You’re trying to use Disney bucks at a Caesar’s Palace here.”

Summer: “That’s a bluff. He’s bluffing, sir. He loves me.”

Riq IV: “You’re a rogue Rick — irrational, passionate. You love your grandkids. You came to rescue them.”

Rick: “I came to kill you, bro. That’s not even my original Summer.”

Summer: “Oh, my God. He’s not bluffing. He’s not bluffing!”

-Dialogue from Rick and Morty, S03E01, “The Rickshank Rickdemption”

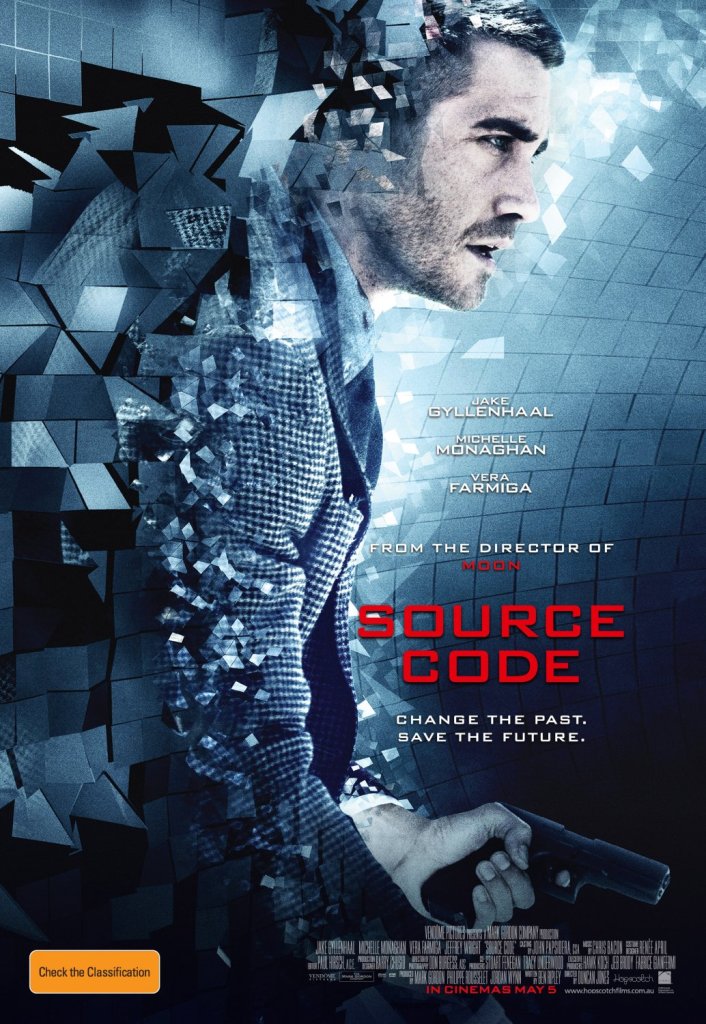

Source Code stars Jake Gyllenhaal as Captain Colter Stevens, a soldier and helicopter pilot sent back in time (or into a simulation, or into a parallel universe), riding inside the mind of a hapless dead man named Sean Fentress (played in reflections by Frédérick De Grandpré) who was killed in a terrorist bombing of a Chicago-bound train this morning, reliving his last 8 minutes over and over again, in order to solve the crime and find the bomber before he strikes again. I recall some muttering when the film came out that it was a bit too conceptually similar to the 2006 Tony Scott film Déja Vu, which featured Denzel Washington as an ATF agent traveling back in time to try to prevent a terrorist bombing in New Orleans, but this is a comparison I quickly dismissed after seeing the film. Both films feature a sci-fi technology that is presented as a one-way conduit for information (from the past to the present), and feature a protagonist who quickly discovers that they’ve actually invented something much more powerful and dangerous. But Source Code is the one that makes by far the more interesting use of it. Because while both films treat the invention of travel between realities as a poorly understood accident, Source Code is the one that implicitly concedes that time travel remains impossible and that events in this version of reality cannot ever be undone. Which means that actions still have consequences, even if we may never see them here. This leaves the viewer to ponder the unfathomable question of what someone can and should do to save lives in another version of reality. Does the knowledge of other worlds make individual lives matter more, or less? Do we have any ethical obligations whatsoever to events and people that, for all intents and purposes, do not exist for us? The film also shares a bit of DNA with the likes of Palm Springs and Groundhog Day (it even includes a Morning Zoo-style radio shout-out at the end), with an aloof time-lord protagonist grappling with how much he should value any individual version of people and events that he encounters, when he knows what they cannot: That they’re all going to die. Or rather, this version of them will die for him when his day resets.

When Stevens first enters the Source Code, he thinks he’s in a simulation. A video game, essentially. He thinks he’s the only real person there, and neither his tone nor his actions matter, apart from achieving the objective of the game. Dr. Rutledge (Jeffrey Wright, doing a prototype of his Westworld mad scientist) encourages this view of his experience, telling him that he can literally shoot every single passenger until he finds the bomber – who cares, after all? They’re all going to die in 8 minutes, and he’s not really the one who killed them. I typically include a quote from the film itself at the start of these 10YA reviews, but this time I included a couple of related quotes on parallel worlds and time travel, because it’s fair to say that there’s a bit of a spectrum in which to consider the ethics, whether through the self-important PreCrime police state of Minority Report, in which people are imprisoned for murders that literally didn’t happen in this version of reality, or the sociopathic nihilism of Rick and Morty, in which Rick Sanchez represents the lonely, wandering, dickish deity who only occasionally lets a human feeling puncture his sheen of dispassionate disregard for the lives of even his own family members. Stevens initially decides that he can do whatever he wants, because as a malfunctioning brain inside a dead shell of his former self, he is not only untouchable, but he sincerely believes he has already given his life for his country, and has no duty to anything or anyone he doesn’t choose personally. That means that if he deems the people on the train to be humans worthy of saving…he’ll try and save them. And it means that all he wants for himself is a chance to say goodbye to his estranged father (played appropriately in a voice cameo by Scott Bakula).

That Stevens died in service to the American military in the tenth year of a war in Afghanistan that is still going on today adds a layer of irony to the events of the film, because it firmly strips away any pretense that the war in Afghanistan – or the suite of constitutionally dubious domestic experiments in surveillance and security theatre – have much to do with preventing acts of terrorism on the homefront. That this particular bomber turns out to be a bland white dude doesn’t change that – this film (like much early 00s pop culture) seems aware that our Middle East focus in the War on Terror was ignoring the mote in our own eye, but after a decade, it’s pretty clear that even this film underestimated the futility of that war. When Rutledge describes Source Code as a “potent new weapon in the War on Terror”, I didn’t find that phrase nearly as jarring, nor was the war such an aloof and disinterested aspect of American culture. Maybe because there are babies born after 9/11 who are now adult soldiers deployed in Afghanistan for reasons they must barely understand at this point. Maybe because we now know that the #1 terrorist threat in the United States since 9/11 is right-wing extremism, and the idea of applying a Magic Eraser to individual acts of terrorism doesn’t feel nearly as satisfying when the terrorists are spawned by the society and political culture that we’re steeped in every day, rather than as a historical consequence of the distant actions of a military-industrial complex that we may cheerlead or ignore in fits and spurts, but which is essentially under the control of the rich and powerful. What’s more, America already has a vast intelligence and special forces apparatus that attempts to do exactly what Source Code is doing: Stop bad things before they happen, usually by killing or arresting the people who we think might do them. It probably serves that purpose some of the time (we don’t really get to know this except when their target is someone famous) – and certainly kills innocent people as well. As Rutledge gets on the phone to rally for more funding for the Source Code project, he could just as easily be discussing drone strikes or targeted close assassinations, and I daresay this connection was probably not lost on the filmmakers, even if they couldn’t know how it would look a decade later, as we’re still conducting wars in exactly the same way.

But enough about the metaphor. Let’s talk about the circumstances. Because it’s an entertaining enough trolley problem on its own. Stevens has been granted the godlike power to save an entire trainload of people, and the burden of being the only person who knows – or at least thinks he knows – that he has this power. Stevens initially believes what his handlers seem to truly believe: that he is experiencing nothing more than a glimpse into the past of a parallel reality. But he quickly figures out that he has entered a fully explorable world, evident the moment that he steps off the train at a stop where Sean, whose body he is possessing, did not. He wanders into the station. He has conversations (and engages in fistfights) that never occurred for Sean. He also kisses Sean’s best friend and potential love interest, Christina Warren (Michelle Monaghan), a couple of times under false pretenses. I will say, two circumstantial factors initially exonerate Stevens here. The first is his initial belief that this is nothing more than a video game. His planting a kiss on an NPC whose dialogue tree indicates that she may respond narratively to a flirting gesture is a purely strategic move, or perhaps just a whimsical one – seeing what’s possible within the game. But as he swiftly concludes that Christina must be a real person (a conclusion he reaches literally on his second runthrough), their final frozen, haunting kiss feels more akin to Brendan Frasier and Rachel Weisz‘s in The Mummy: “I dunno; I thought I was gonna die – it seemed like a good idea at the time.” I’m being glib here not because men suddenly kissing strangers has gotten any less creepy IRL in the intervening years, but because I reached a similar conclusion here that I did watching Palm Springs: I’m not going to pretend like I have a definitive moral framework through which to judge someone engaging in romance while trapped in a time loop, particularly in this case, when Stevens’ brain is barely under his own control. Narratively, however, I’m happy to judge it, because I’ve now seen Michelle Monaghan ably play a second-fiddle detective’s assistant/lover on at least four occasions, and it’s well-past time that she gets her own mystery to solve and moral ambiguity to throw herself into. She’s earned it! A Knife Out for Michelle, please.

Vera Farmiga is in a more interesting place here, because the vibe I got at the start of the film was that Captain Colleen Goodwin feels dubious about what she’s doing and saying to Captain Stevens, who she knows is just a jacked-up brain in a jar with a bit of his old body still attached. Her resulting manner feels like something akin to a hospice or memory care worker – caring, but clinical, serving objectives that she knows can never be fully understood by her patient. But by the film’s end, we are forced to consider the possibility that this version of Colleen Goodwin might have known all along – or at least had received a mysterious email purporting – that Source Code has the potential to travel to parallel worlds. And her every action, including telling Stevens that trying to save people on the train would be “counterproductive” – must now be viewed through that lens. This is only one possible interpretation of the ending (which also introduces the possibility that they may have wiped Stevens’ memory on one or more prior occasions), but it’s the one I prefer, because it’s the one that makes Goodwin the most interesting as a character. It forces the viewer to imagine what they would do if told that their day job has multiverse-altering implications, but in a way that can never be proven, because it relates to events that were foiled in this universe. What percentage of the time might you think that it’s a hoax? Might the potency of this belief fade over time? Might you find yourself returning to the day-to-day drudgery of dissecting successful terrorist attacks, which – from your perspective – never actually end up getting foiled? Goodwin’s career-ending sacrifice at the end of the film feels even more powerful when considered through a lens of sudden, powerful existential regret.

Which leaves us with Sean. Poor, poor Sean, merged with Stevens, a Tuvix-caliber cosmic joke, staring into the Bean at his own reflection, which will never again match his internal concept of himself, on a date with a woman he never met before today. It is the reflection of a man killed in a terrorist bombing, only to be erased 8 minutes early a thousand times more, because he happened to most closely resemble a soldier who died in another reality. When I think of how Stevens must regard himself, I’d put him between a rock and a hard place. The most decent thing he could do once he no longer has the imminent fear of death as an excuse, is to let Christina go and make some new friends – but he has little incentive to do so, other than how he’ll personally feel about it. And facing a lonely new universe, it’s easy to imagine him taking the default, monstrous choice of continuing a romance he hasn’t earned, even if I doubt I’d much enjoy seeing that movie (which was called Passengers). Sean may also have family that Stevens will have to go through the motions with – it’s the minimally decent thing to do at this point. But he may find it quite as difficult as Jean-Claude Van Damme at the end of Time Cop – it’s hard to act normal with a family you only just met in this reality. You don’t have any context for normal. On the flip side, when I think of this from Sean’s now-absent perspective, and consider what he might want for himself out of this horrific situation, I’m surprised that I don’t have a ready, simple answer like, “I’d rather just die.” Other than the visceral creepiness of my body playing out several more decades of Weekend at Bernie’s after my death, I suppose all I can do with such an ending is hope that the guardian angel who couldn’t save me, but did save a bunch of people around me, uses my body and my name in ways I would approve of for the rest of his version of my life? This would absolutely bother me if my consciousness still existed to be aware of it (as is perhaps the case in a more recent example), but if I had to choose, for my loved ones, the experience of me being horribly killed in a terrorist bombing vs. unknowingly replaced with a guy who seems basically decent and well-meaning (and who was horribly killed in his own reality), but isn’t me… I’d scream, I’d cry, I’d lament the abject horror and unfairness of such a choice, but in the end I’d have to pick one or the other, and in my heart of hearts, I can’t say for sure which one it would be. Which makes this is the second of two entries in Duncan Jones‘ filmography that ended with an effective and enduring existential mindfuck, and that definitely counts for something.

FilmWonk rating: 8 out of 10