This review originally appeared as a guest post on 10 Years Ago: Films in Retrospective, a film site in which editor Marcus Gorman and various contributors revisit a movie on the week of its tenth anniversary. This retro review will be a bit more free-form, recappy, and profanity-laden than usual.

“Once more into the fray. Into the last good fight I’ll ever know. Live and die on this day.”

“I died with my brothers – with a full fucking heart.”

“When your time comes to die, be not like those whose hearts are filled with fear of death, so that when their time comes they weep and pray for a little more time to live their lives over again in a different way.

Sing your death song, and die like a hero going home.“

“Theirs is not to reason why, theirs is but to do and die.”

John Ottway (Liam Neeson) is no poet, but his dad was, as well as being a “clichéd Irish motherfucker when he wanted to be. Drinker, brawler, all that stuff”. His cartoon leprechaun of a father really isn’t the problem here, nor is his obviously dead wife, who manages to appear in identical flashbacks six separate times, lying in bed saying “Don’t be afraid” in full hair and makeup while – as is revealed about 20 seconds before the end credits – bloodlessly dying of a terminal disease. Nor is the problem Ottway himself, whose opening monologue awkwardly admits that he is surrounded (at the remote Alaskan oil drilling site that is his workplace) by assholes, ex-cons, fugitives, and drifters. Nor is the problem that he uh…”moves like he imagines the damned do” (whatever that means). Most of the verbal or voiced-over attempts to add depth to these characters read as generic screenwriting stand-ins that probably should have been replaced with something more poetic later on. Ultimately, none of it was replaced – The Grey just kinda kept piling it on. And a decade ago, I scoffed and waited impatiently for the wolf-punching to begin.

People face death for a lot of unnecessary reasons in a society that treats many humans as disposable instruments of empire-building, and some of them are inclined toward poetry in the process. What’s more, a lot of poetry has been written for them, often by people who have no sense of what they’re describing – educated and pampered cultural elites who haven’t faced a shred of real danger, and would wordlessly shit themselves if they ever did (film critic says what?). After five million dead in two years of COVID (and a million more per year from tuberculosis, before and since), I suppose I may just be done scoffing at the dying of the light for a while, or meandering, febrile attempts to make sense of it before the moment comes. Let the damned speak their piece. Not like anyone’s going to do it for them.

I revisited The Grey because I feel as if I’ve become a more charitable critic in the intervening years, and this one stuck with me more than I expected it to. I stand by most of my previous reviews, but that’s not to say I’ve never changed my overall opinion of a film. Listening back to our podcast for The Grey, I was, I must admit, an insufferable snark monster about this film. I respect the craft involved. For cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi – who was hot shit for a few years there, filming for the likes of David O. Russell, Scott Cooper, and Tom McCarthy – to shoot something this coherent in blackness and snow, with a mostly CGI wolf-pack that spends most of its time hunting and striking in the dark, is a real accomplishment (even if the absolute king of this is still Emmanuel Lubezki on The Revenant). The sound design (from supervisors David G. Evans and Mark Gingras) is crucial as well, giving personality, bearing, and distance to the wolf pack as they are barely perceptible in the howling winter. Two things are simultaneously true of this film: It is a better-than-average survival thriller with a middling script, whose performances, with broadly interchangeable and equally doomed men, are each given an artisanal touch by their performers that the film’s various death monologues sorely needed. And God help me (or – fuck it – I’ll do this one myself), I enjoyed this film a lot more this time around, perhaps because I’m entering middle age, and death is no longer the kind of distant hypothetical annoyance it was at the height of my mid-20s energy and arrogance.

I must confess, I’ve spent the last decade inadvertently spreading a bit of misinformation about this film – for me, this was always the one that fraudulently sold itself as “the Liam Neeson wolf-punching movie”. As Ottway dons his improvised death-knuckles (made of tape and broken miniature liquor bottles) for his final showdown with the Alpha Wolf (guarding the den that it turns out the group was wandering toward this whole time), the film ends as each animal lunges toward the camera. Cut to black, and credits. My younger self was annoyed, and would tell anyone who would listen that there is no wolf-punching in this goddamn movie. As it turns out, that wasn’t and isn’t true. It’s a bit hard to see in the crash-site mire and darkness, but Ottway does punch a wolf about 25 minutes into the film, during one of the first attacks amid the wreckage. Then Diaz (a pre-Purge, pre-MCU Frank Grillo) stabs and eventually decapitates one. It’s just all very dark and muddy and incomprehensible, which bugged me at the time, but is pretty clearly a deliberate choice in retrospect. Anyway, fuck it. Jeremy Renner fist-fought a wolf the very same year in a scene that has aged rather poorly, and suffice to say, this was always a bit of a “be careful what you wish for” scenario.

Ottway’s barking atheism in the final scene is a powerhouse moment for Neeson, who didn’t acknowledge any real-world influence in Ottway’s expression of grief for his late wife in this film, but invited the audience to draw their own conclusions. The man slumps by the side of the river, a lone and temporary survivor of an animalistic slaughter, bargaining with a god he no longer believes in. And it lands. But the moment when his performance started to click for me was much earlier in the film, when the time comes for Ottway to take Diaz down a peg by mocking his masculine bravado and admitting, for all of these roughnecks to hear, that he is scared shitless. Of course, the scene ends with Diaz pulling a knife and demanding Ottway fight him, echoing a challenge that we hear taking place offscreen between a pair of wolves – the Omega and the Alpha, Ottway tells us. And each pack of animals settles their business in similar ways. Ottway throws Diaz to the ground and disarms him. Then he gives back the knife with a quick “No más”. Diaz, in spite of himself, starts to apologize before the Omega shows up, outcast to a quick death to test the humans’ defenses. There’s a very loose and messy statement about violence and toxic masculinity at work in this scene, with no clear conclusions, but it is interesting to hear these men debate how much of society’s basic decency has followed them into this situation (including whether to loot the bodies for supplies and wallets), when it appears the only thing keeping them together is Ottway’s persuasive threats to start beating the shit of any malcontents in the next five seconds. This clear and natural mantle of leadership brings the group together as brothers in arms (minus the arms) with a plainly obvious chain of command: Ottway is the Alpha.

Despite their bravado, each of them still manages to visibly weep whenever one of their brothers gets killed before their eyes, even if they don’t even know each other’s first names until the end. This idea – of fighting for the man next to you – is nothing new to this film. It’s a war movie trope just as surely as the poetry above (which I borrowed from The Grey, Lone Survivor, Act of Valor and…a 170-year-old Tennyson poem). And yet it always rings a true in the moment, because with the knowledge that everyone dies alone, there is something intuitive about a person facing a senseless, violent death right in front of you and recognizing that the least you can do, in the interests of your shared humanity, is to hold their hand and feel bad for them. The group takes the small, defensible moments between attacks as an opportunity to wax religiously, with Talget (Dermot Mulroney) insisting that God must have spared them all for a reason, and his buddies pointing out that Flannery (Joe Anderson) and Hernandez (Ben Bray) were “spared” as well, only to be eaten by wolves. Ottway and Diaz argue from separate places grounded in firm atheism: Diaz, out of cynicism and spite worthy of a PureFlix origin farce starring Kevin Sorbo, and Ottway, radiating sincere regret. He’s done with God, but he remembers his days of faith and misses them – something I found relatable, even if I’m also not keen to go backward.

There’s a reason why all this death poetry rings familiar and runs together for us. We tell the same stories over and over again about this mortal coil because we occasionally find comfort and meaning in them. And the less the world makes sense to us, the more elusive that meaning can be, which may be why a new study in the Journal of Religion and Health indicates that self-reported religious faith has plummeted during the COVID-19 pandemic – a reliable effect across religious and spiritual people from all prior levels of devotion. In a world so full of senseless death and dubious purpose, perhaps that’s why a simple survival story landed better for me this time. These guys – these assholes, ex-cons, fugitives, and drifters, don’t have to fix the world they’re helping to break by drilling for Arctic oil, any more than I have to do so as one of the complicit billions buying and burning it. They’re in a survival situation that feels primal and essentially human. No tools apart from their brains and muscles, and their ability to use them collectively (including one pretty awesome cliffhanger action scene – one of the few things I also liked the first time I saw the film). The world, such as it is, ceases to matter for the duration of this story. Which makes the story feel like it matters more.

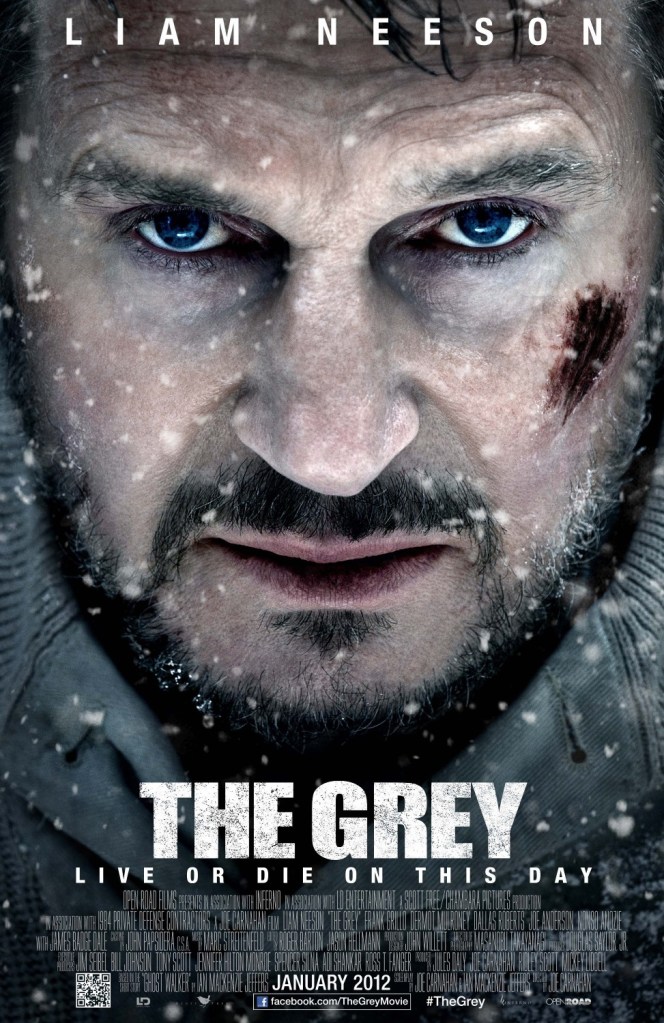

The last line of poetry above, Theirs is not to reason why, theirs is but to do and die, was written by Alfred, Lord Tennyson in 1854, in “The Charge of the Light Brigade”. That last bit must have been too grim for modern audiences, because it has mutated over time to “Theirs is not to wonder why; theirs is but to do or die”. A simple twist of grammar turns an imposed suicide mission into chosen heroism. The poster tagline for The Grey suffers from a similar mutation – Live and die on this day, a trifling poem by Ottway’s terrible father, becomes Live or die on this day, a trite piece of studio marketing which definitely suggests that survival is both the point and a possibility. Perhaps that’s why The Grey let me down the first time. A false bill of fictional goods doesn’t bother me so much anymore. Tennyson led an interesting life and became a beloved historical poet, but he was a pampered Victorian aristocrat who never saw hide nor hair of whatever the fuck the Crimean War was about, so I won’t be too outraged on his behalf for his message being lost in the clichés. But I’ll spare a thought or two for the dead men he wrote some poetry about. And whichever wolves devoured them, lest they be devoured themselves.

FilmWonk rating: 6.5 out of 10

Pingback: FilmWonk Podcast – Episode #194 – “Kimi” (dir. Steven Soderbergh), “Blacklight” (dir. Mark Williams), “I Want You Back” (dir. Jason Orley) | FilmWonk