Last week, I had a chance to catch up with the 2009 Academy Award winner for Best Foreign Film, Yôjirô Takita’s Departures. The film stars Masahiro Motoki as Daigo, a Tokyo cellist who finds himself out of a job after his orchestra is disbanded, and is forced to move back to his hometown with his wife Mika (Ryoko Hirosue). He reluctantly takes a job as an encoffiner, performing a series of delicate ceremonies to prepare a recently deceased body and place it in a coffin before the family. He initially acts as an assistant, gradually learning the trade from his boss, Ikuei (Tsutomu Yamazaki).

The film initially seems to rely on a knowledge of Japanese culture, attitudes, and rituals surrounding death, and it quickly becomes evident that Daigo’s employment, while financially lucrative, is not considered remotely respectable in society. He keeps the job a secret from his wife, and is subject to constant shame by the townspeople. In the first act, the film strangely takes on the air of a quaint little after-school special. As I took stock of this seemingly contrived intolerance from my cynical American perspective, my reaction was pretty dismissive: Wow, those Japanese sure are uptight about death.

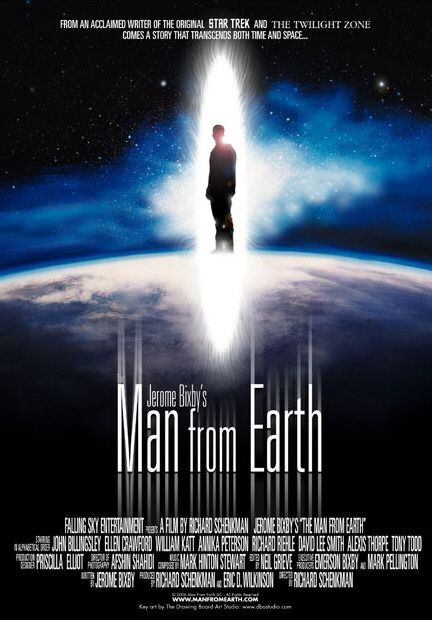

If that’s all Departures had been, my [borderline offensive] reaction would have likely remained unchanged, and I may have found the film to be a waste of time. In fact, this film – with its 131-minute runtime, ponderous themes of life and death, and frankly masturbatory poster shot (above) – seems to fit the exact formula for a film that’s likely to be seen by no one. But in spite of my initial reaction, I found myself completely drawn in by it. As the film goes on, it proves itself an adept and thoughtful exploration of the ritual of mortality, driven by some very strong performances.

We see many “prepping the dead” scenes performed in front of the families of the deceased – each one almost plays out like a short film, and the first has several unexpected comedic beats that aptly set up the tone of the film. For a film about death and mortality, Departures turns out to be surprisingly light viewing. And while showing the entirety of each death ritual for several minutes at a time may have dragged out the film, I found it to be a brave and surprisingly effective choice. Joe Hisaishi’s score is particularly striking throughout the film (and in these scenes in particular). There are a number of sequences in which the film cuts back and forth between Daigo prepping a body and playing his cello – even prodding the fourth wall a bit as the score syncs up to accompany him. It’s a shameless and slightly jarring trick, but the illusion never quite breaks, and the film’s none-too-subtle parallels between playing the cello and prepping a dead body are aptly conveyed.

It certainly helps that Takeshi Hamada’s cinematography is absolutely gorgeous. We get the sense that Daigo’s hometown of Sakata is meant to be a bit of a dive, but you wouldn’t know it from the scenery. As Daigo preposterously plays his cello outdoors in the winter cold (a feat that would probably crack it down the middle in real life), I just couldn’t stop marveling at the wondrous backdrops and taking in the rich, flowing orchestral beats.

But as the film went on, I was struck the most by the beauty and dignity of the death rituals, and chastised myself a bit for the “after-school special” vibe with which I cast the film initially. Are the Japanese uptight about death? Certainly. But we all are, even if American culture handles it with slightly different ritualistic trappings. Daigo and Ikuei may not be well-respected, but the film effectively conveys the nobility of their profession.

FilmWonk rating: 7 out of 10

Mild spoilers will follow.

I wish I could end my review here, but the fact is, Departures takes a 15-minute detour at the end that I found completely jarring and unnecessary. Much of the film’s conflict stems from Mika’s disapproval of Daigo’s profession, and it’s not much of a spoiler to say that she eventually changes this opinion. While the character transformation is fairly standard, it is Ryoko Hirosue’s performance that made me completely buy it. She starts off as a devoted and loving wife – visibly bothered by their new living situation, but staying supportive. As the film goes on, the character could easily have turned shrewy, but Hirosue keeps her completely sympathetic, and her chemistry with Motoki is impressive. And then, not two minutes after that conflict is entirely and satisfactorily resolved (in front of another needlessly gorgeous outdoor backdrop)…

Someone else dies. And no, it’s not who you think, because this fresh corpse has not been around for any part of the film. We’re treated to a shocking revelation about a secondary character that comes completely out of left field, and the ensuing plotline completely abandons and undermines the well-established surrogate father/son relationship between Daigo and Ikuei (and aided by their masterful performances). The first two hours of this film felt like a complete story, but this denouement sent it completely off the rails. Much like this review, Departures would have been better off ending just a little sooner.