This review originally appeared as a guest post on 10 Years Ago: Films in Retrospective, a film site in which editor Marcus Gorman and various contributors revisit a movie on the week of its tenth anniversary. This retro review will be a bit more free-form, recappy, and profanity-laden than usual. Further, it contains candid discussion of kidnapping, child abuse, and sexual assault as it pertains to the film’s subject matter.

I always believed it was the things you don’t choose that makes you who you are. Your city, your neighborhood, your family. People here take pride in these things, like it was something they’d accomplished. The bodies around their souls, the cities wrapped around those. I lived on this block my whole life; most of these people have. When your job is to find people who are missing, it helps to know where they started. I find the people who started in the cracks and then fell through. This city can be hard. When I was young, I asked my priest how you could get to heaven and still protect yourself from all the evil in the world. He told me what God said to His children. “You are sheep among wolves. Be wise as serpents, yet innocent as doves.”

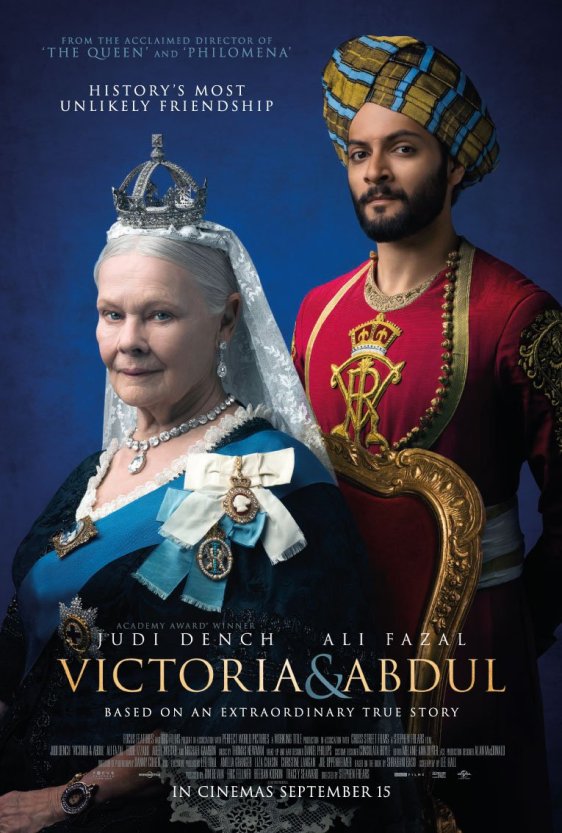

Opening voice-over is hit-or-miss with me, but this is the second 10YA film and review that I’ve began with that clause, so it’s as solid a framing device as any. Or at least better than what I feel obliged to start with, in light of the past few weeks. Gone Baby Gone is a film that I remember fondly. It’s a compelling detective story with a provocative ending, it launched the surprisingly laudable directing career of Ben Affleck, and it helped to launch the lead-acting career of his younger brother Casey (which includes one of my favorite films of this year). It continued a long collaboration between the elder Affleck and Miramax, the production company co-founded by the ignominious [alleged] sexual predator Harvey Weinstein and his brother Bob (who had already departed for The Weinstein Company by 2005, and had no involvement with this film). Meanwhile, Casey Affleck was sued in 2010 for alleged abuses of his female co-workers on and off set (the suits were settled under terms of confidentiality), Weinstein has been revealed to be a rapacious creature on par with Bill Cosby or Donald Trump, and a litany of actors and producers (including Ben Affleck) have lined up left and right to excoriate Weinstein out of one side of their mouth, and grouse unconvincingly that they didn’t know a thing about it out of the other.

These 10YA retrospective reviews are meant to showcase how my thinking on a film has changed since I first saw it a decade ago, and one belief has certainly not changed: Art must stand on its own. It’s the inanimate product of a thousand decisions by a thousand people. While I still occasionally nod to my auteurist leanings by referring to a film as the possession of its director (as I’ve done in the headline above), I recognize that it neither exists in a cultural void, nor is the product of a single voice. I can’t judge art retroactively by the artists that created it, no matter what happens afterward – although it’s a fine argument for expanding the pool of artists. That said, all of this sucks. My awakening to the hardships of sexism, discrimination, harassment, and assault that women are categorically more likely to face is older than the past few weeks, but its latest hashtag iteration (#MeToo) is a grim reminder. I still believe that art must stand on its own, but it is equally true that art can have a cruel human cost that taints it in retrospect. And I’d be lying if I said that this feeling of disappointment wasn’t on my mind while re-watching this film. I’ve been writing about film for over a decade, and right now, Hollywood and its margins give me an icky feeling, just as surely as the casual outspoken racism, sexism, and homophobia of older films. Society will move on, and some of these people – who either did wrong, or knew about it – will have their misdeeds ignored, or experience tepid, PR-friendly redemption narratives, or win Oscars (some already have). And we’ll be judged by history accordingly. Now on with the film.

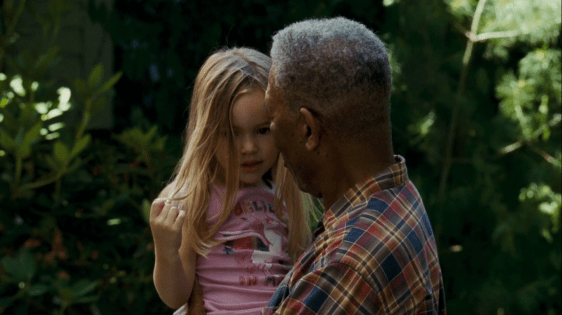

The missing little girl is Amanda McCready (Madeline O’Brien), and she’s understandably not present for much of the film. She is stolen from her bedroom in a dank apartment ill-maintained by her mother Helene (Amy Ryan), and as we begin the film, her disappearance is a known quantity, and Lionel and Bea (Titus Welliver and Amy Madigan), Helene’s brother and sister-in-law, are in the market for a pair of detectives to supplement the police investigation. There’s no love lost in this family – Helene openly mocks Bea for her infertility, and Bea refers to her as an abomination. “Helene has emotional problems,” says Lionel. “It’s not that, Lionel… She’s a cunt,” says Bea. Ryan is simply marvelous as Helene, flitting between disinterested party girl, casual Boston racist, and broken, prideful parent with incredible ease. Her television career runs the gamut from The Wire to The Office, and all of her range is on display here. Helene is…not a charmer. And her unreliability and unfitness as a mother is essential to the film’s ending.

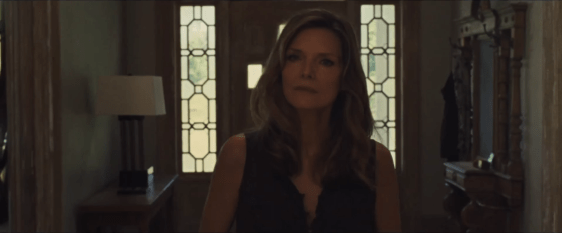

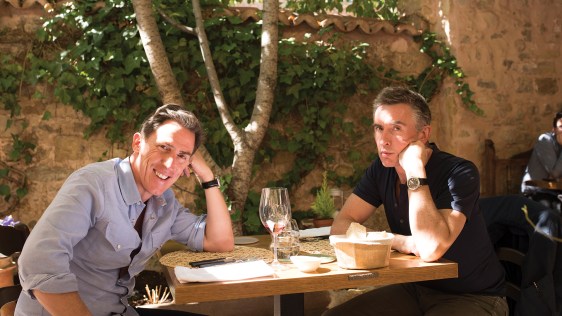

The detective couple is Patrick Kenzie (Affleck) and Angie Gennaro (Michelle Monaghan). If I might rave about Monaghan for a moment, this is an actress who spent much of the 2000s in do-nothing love-interest roles, and is frankly a talented enough performer to deserve better. This film, along with Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, is one of the few opportunities she’s had to do something interesting on-screen. Angie and Patrick have several private chats about how to proceed over the course of the film, and her reluctance to take on the case is key. She’s a skilled detective who doesn’t want to take on a missing kid – not because she’s afraid they won’t find her, but because she’s afraid they will – either dead in a ditch, sexually abused, or both. As police captain Jack Doyle (Morgan Freeman) – whose backstory includes a murdered child of his own – puts it, “I don’t care who does it. I just want it done.” In light of the film’s ending, it’s hard to make sense of these initial reactions as each character joins the investigation, but the film does thoroughly sell the notion that anyone who willingly investigates a kidnapping is performing an important duty, but also welcoming abject horror into their life.

Patrick and Angie head for a local haunt and interrogate some barflies, who quickly reveal that Helene was not across the street for a quick sandwich when her daughter was taken, but rather pounding rails of coke and getting busy with her boyfriend Skinny Ray in the bathroom. This is where we first learn of a violent Haitian drug lord named “Cheese” Jean-Baptiste (Edi Gathegi), for whom Helene is occasionally employed as a drug mule. Then it gets nasty, words are exchanged, all of the barflies get aggressive and start threatening the pair with violence and sexual violence respectively. Patrick pulls a gun, and they leave to meet their fellow investigators assigned by Captain Doyle: Sgt. Detective Remy Bressant (Ed Harris) and Detective Nick Poole (John Ashton), who introduce a possible suspect, convicted pedophile Corwin Earle (Matthew Maher), who’s known to hang out with a couple of cokeheads. Not much to go on – and Remy and Patrick have great fun throwing barbs at each other. “You got something to contribute, be my guest,” says Remy, “Otherwise, you can go back to your Harry Potter book.” At which point Patrick gives up the goods on Cheese, and they go to interrogate Helene (after briefly pausing to hand off the pedophile info to a shady acquaintance, played by Boston MC Slaine).

This is all an odd sort of mash-up between a police and private investigation (which seems to be author Dennis Lehane‘s specialty). Helene is confessing to multiple felonies in the course of this, and Remy vacillates between mocking her obvious half-truths (“No. It don’t ‘sound familiar’, Helene. He’s a violent, sociopathic, Haitian criminal named ‘Cheese’. Either you know him or you don’t.”), and demanding whether she even gives a fuck about her kid. This is all terribly convincing, perhaps because both Remy and Lionel already know where Amanda is at this point, and their disapproval of Helene’s lifestyle is the one sincere detail of the scene. Regardless, it plays brilliantly. Helene confesses that she and Skinny Ray conspired to steal drug money from Cheese (under cover of the police busting their contact and seizing the drugs), which makes all of the investigators in the room presume aloud that Cheese kidnapped Amanda for ransom. They all drive over to have a chat with Skinny Ray.

Helene rides with Patrick and Angie, and they bond over some casual “faggot” talk about a mutual high school acquaintance. This is how blue-collar Boston talks. Got it. Helene is still not taking this particularly seriously, but she does lay out her self-inflicted dilemma: She couldn’t just call Cheese and confess to ripping him off, and she couldn’t just tell the cops that she ran drugs. Amanda disappeared, and she had no recourse but to report the disappearance and hope for the best. She also reveals that she hid the money. From everyone, including poor Skinny Ray, whom they find tortured and shot to death. And this is when Helene finally loses her shit. As soon as she sees Ray, it suddenly becomes real for her. She knows Cheese must’ve taken Amanda. She knows it’s her fault. She remembers that when she left Amanda alone at bedtime, the last thing the child said was that she was hungry. Helene wonders whether they fed her – begs Patrick to tell her that her daughter isn’t still hungry. I was prepared here – this is the part of the film that I expected to bother me more, as one of the things I’ve done in the past decade is have a child of my own. And it’s fair to say, I did find these scenes (and the whole concept of a kidnapped child) a bit more upsetting than I did the first time. But…not as much as I expected to. Perhaps because this time through, I knew Amanda wasn’t in any real peril, and perhaps because she’s little more than an offscreen MacGuffin for most of the film. Helene’s emotions are real (and Ryan renders them brilliantly), but she’s such a selfish and unfit parent whose feelings are so fleeting that I had a hard time internalizing them. Sure, she wants her kid to be fed, warm, and safe – and these are feelings I can relate to. But she didn’t bother to feel them until a half-day past the coke wearing off, and I assume another quick bump will sort that out. The team digs up the money (which was buried in the backyard, 20 feet from where Ray was being tortured – poor bastard), and makes a gameplan. Remy and Nick acknowledge that if this is a kidnap for ransom, they have to bring in the FBI. Patrick and Angie volunteer that they can do what the cops cannot: negotiate with Cheese for a clean swap – the money for Amanda (no one seems overly concerned with avenging Skinny Ray). So off they go.

Gathegi plays a marvelous cartoon gangster in this scene. This is an actor I’ve seen pop up all over TV and the occasional film over the past decade, and he’s always a pleasure. He plays up the Cheese shtick for a bit, declaring that, “Bitches love the cheddar.” I turn to my wife and ask, “Do bitches love the cheddar?” She considers a moment, and says, “Yes.” Good. That’s why I always keep a loaf of Lucerne Sharp in the fridge – as true a decade ago as now. Meanwhile, back on the screen, Cheese is not happy. If we believe the Haitian, not only did he have no idea he’d been robbed, he doesn’t know anything about a kidnapped girl, and is offended by the suggestion that he’d ever mess with a child. He pulls a gun, demands that Patrick lift his shirt to reveal any wires, demands the same of Angie a bit more aggressively, says the title of the movie aloud, and insists that he’s not involved. Patrick stares him down and issues an extremely elaborate threat to ruin Cheese’s life and business if he’s lying. Cheese points the gun in his face and offers to get “discourteous” if they should ever return. Patrick doesn’t blink. Man this scene is great.

The cops don’t buy it, and start surveillance on Cheese, who promptly calls into the police station offering to make the trade – Amanda for the money. Captain Doyle has a transcript of this call, and is pissssssed that his officers have involved him in an illegal ransom exchange without his knowledge or consent. And he agrees to make the deal anyway – nice and quiet. At this point, Angie is the voice of reason in the room, asking whether keeping the deal quiet is better for Amanda…or better for them. Doyle promptly shuts her down with the my child was murdered card, which is…admittedly a pretty good card. He insists he cares as much about Amanda as anyone in the room, and believes that this is the best way to keep her safe. Freeman…sells this deception well. We don’t learn until later that the whole point of this farce at the quarry is to fake Amanda’s death and throw Patrick and Angie permanently off the trail, but Doyle is speaking the truth when he says he believes this is what’s best for Amanda. And so it plays out. We see a gorgeous flyover of the flooded quarry at sundown. Then cut to darkness. They take their positions on opposite sides, in accordance with Cheese’s “instructions”, and all hell breaks loose. Shots are fired in the distance, and Patrick and Angie run around to the scene to find Cheese dead on the ground. There’s a splash – someone or something went into the water. All of the dudes stand around dumbfounded, and Angie jumps the fuck off the cliff into the water to rescue the girl. It’s downplayed, but this is an awesome and quite dangerous piece of heroics. Angie is the one who didn’t want to find a dead child, and she’s the first to leap for that possibility – good on her. But it’s all for nothing. We cut to Angie in a hospital bed, where Patrick tells her that divers are searching the quarry. Nothing is found – Amanda is presumed dead, and Angie blames herself. Captain Doyle takes official responsibility, loses half his pension, and retires. Helene gets a death certificate and a donated casket, and life goes on. I honestly can’t recall how I felt watching this a decade ago. I asked my wife afterward how she felt at this point, and it all seemed familiar: Hopeless. Aimless. Disappointed. Unsure how there could still be 40 minutes left in the film.

Two months pass, and a boy has gone missing. I’m going to TL;DW this sequence: Patrick’s contact tells him he’s located the pedophile from earlier, Corwin Earle. Remy and Nick show up for backup, an extremely well-staged shoot-out ensues, and Patrick enters Earle’s upstairs room to find him whining on the floor that “it was an accident”. A series of horrific montage shots: the missing boy is dead in the bathtub, Patrick vomits, Earle begs for his life, and Patrick executes him on the spot with a shot to the back of the head. I don’t want to write any more about this, because frankly, this is the part that disturbed me more as a parent. I’m with Angie on this. I know that a dead child is a necessary plot element in this film. I know that murdered children exist in real life. But I don’t want to see it. I don’t want my lizard brain to become terrified of every stranger and dark alley, when the people I know, and who have a pre-existing relationship with my kid, are statistically more likely to kidnap or harm him – and the overall risk of such an event is extremely low compared to more mundane harms. I know that. But I also know that I don’t want to ponder that scenario, because I’ll want to lock my child indoors and hold him in my arms and never let him go. As I recall my reaction from a decade ago, I was as baffled and disturbed by this sequence as my wife was this time. She said afterward that she was wondering what the point of all this would be – just an extended Law & Order: SVU episode? And then, finally, it all comes together.

In the next scene, Remy – whose partner Nick was fatally shot – drunkenly comforts Patrick about the summary execution. I haven’t said much about Ed Harris, but he also gives a fine performance in this film. In the fundamental conflict at play in this film, he represents the side of vigilantism, and he argues his case well. Many years earlier, he and his soon-to-be-dead partner received a snitch tip from Skinny Ray about a minor criminal, and they raided his house. And in that house, they found a disgusting hovel with pair of strung-out criminals, but no drugs – and an abused, neglected child in an immaculate bedroom who just wants to tell Remy all about how he’s learned his multiplication tables.

“You’re worried what’s Catholic? Kids forgive. Kids don’t judge. Kids turn the other cheek. And what do they get for it? So I went back out there, I put an ounce of heroin on the living room floor, and I sent the father on a ride. Seven-to-nine.”

“That was the right thing?”

“FUCKIN’ A. You’ve gotta take a side. You molest a child, you beat a child, you’re not on my side. If you see me coming, you’d better run, because I’m gonna lay you the fuck down! … Easy.”

“It don’t feel easy.”

This exchange, right here, is what this film is all about. It’s imperfect, grandiose, and both of these men have violated the principles that they claim to believe in. It describes the War on Drugs in myopic, moralistic, clash-of-civilizations style terms, and I’ll be honest – a decade ago, despite leaning college-libertarian at the time, I probably would’ve taken this at face value. Jack Bauer spent a decade popularizing torture in the War on Terror. These guys – along with every cop flick since the 1980s – justified vigilantism in the name of a war on a convenient other – “drug-people”, who aren’t like us regular, law-abiding citizens. It’s only the reluctance, and the moral complexity of the film’s ending, that makes this a better treatment of this issue than most. Because we know now what comes of fighting a war the way that Remy describes. More war. Mass imprisonment. An ouroboros of societal decay. And at the same time – you ask me what I’d like to do with someone who harms a child (which the film is keen to associate with the war on drugs, not entirely unfairly), my lizard brain says the same thing as Remy: Lay him the fuck out. It’s not a rule to run a functional civilization with, but it’s sure as hell satisfying. But more importantly, it causes Patrick to realize that Remy has been lying to him – he pretended not to know Skinny Ray during the investigation, but the dead man had been snitching to him for a decade.

This isn’t the last great scene in the film – there’s a tense moment back at the Fillmore bar, where Patrick confronts Lionel about his involvement with Amanda’s disappearance, Remy shows up in a mask to stop Lionel from telling him the truth under cover of a fake armed robbery (and the movie makes almost no effort to hide his identity from us), leading to a shootout and chase in which Remy dies on a rooftop proclaiming that he loves children. The exposition of this conspiracy (between Lionel, Remy, Nick, and Captain Doyle – without the knowledge of Bea, who hired the two detectives) feels a bit rushed, but is probably one of the tightest and most coherent reveals this side of Gone Girl. It’s a great sequence, but as I often say of falling action, I don’t have much more to say about it. At this point, I was just waiting for the consequences. Patrick and Angie wind their way down a wooded lane and arrive at the home of the retired Captain Doyle, only to find Amanda McCready, alive and well, where she has been the whole time.

And Patrick faces another choice between law and vigilantism. Does he do his duty, telling his client that he’s found her missing niece, and send Captain Doyle and the surviving conspirators to prison? Or does he leave her there? Angie’s answer is clear – leave that child where she is, in that safe, affluent house where a nice couple makes her sandwiches. I do wish the conversation between Patrick and Angie had been a bit longer – all that we gleaned of Angie’s point of view was that she was so glad to see Amanda alive that she was willing to do anything to see her safe. She warns Patrick that she’ll hate him, he does the stoic detective thing and calls the cops, Angie leaves him, and that’s that. All the conspirators go to prison, and we cut to Patrick visiting Amanda and Helene on any given Friday, with Helene about to go out for the evening. And Patrick realizes that Helene is still a terrible mother, and by making this choice, he has essentially volunteered to be Amanda’s babysitter until adulthood. This is a fine ending – it seems to be a marginally less disturbing version of a village raising a child than the conspiracy of Amanda’s relatives and the police to steal her away. Kids forgive. Kids turn the other cheek. But they still need meals and blankets and hugs and rides to school, and once a grownup – any grownup – has decided to take on that responsibility, they have a duty to keep it up for as long as the kid needs them.

But let’s talk some more about that moral choice. When Patrick arrives at Doyle’s house, he has to decide whether to continue – and become an accomplice to – Amanda’s abduction. While this dilemma prodded my incredulity a bit, I was willing to accept it on its own narrative terms, because it’s fundamentally the same question about vigilantism that he and Remy had discussed regarding the shooting of a criminal or planting of evidence. It’s about going outside the law to pursue your own definition of justice. The state holds a monopoly on deprivation of civil liberties for a reason (whether we’re talking about executions or forced forfeiture of children), and while our system of social services is an imperfect, underfunded mess that’s rife with abuses and due process violations of its own, it’s hard to imagine a situation where carrying out a life-long extrajudicial disappearance ends well. Not even a state could do this – I mean, it’s literally a crime against humanity for a reason. Amanda may well need to be taken away from her mother – at least one of the anecdotes was of Helene leaving her in a hot car and nearly killing her. But denying a mother closure on her child’s fate is a cruel and unusual punishment. That’s not my opinion – it’s legal fact, even as applied to a mother as execrable as Helene. For a film that strove for some ambitious moral complexity, I’m inclined to think that making Amanda a 5-year-old was a misstep. This is a girl that’s old enough to remember her former life. When we see her at Doyle’s, she seems to be treated well – but when you really think about what she’d have to look forward to in this scenario, she would be a phantom, hiding her true name and face in public, and only living half a life.

This ending forcibly called to mind the story of Elizabeth Smart, who was abducted as a teenager in 2002, forcibly “married” to a religious extremist (who horrifically abused and raped her over the course of nine months), until she was found on a public street with him and an accomplice. I don’t imagine that Doyle and his wife would dream of hurting Amanda – but I have to believe that the mere act of plucking her away from reality is still an act of abuse. Morgan Freeman was 70 years old when this film was made. Did Doyle expect to hide this girl from the world until his mid-80s, when she presumably found her true identity on Google or while applying for student loans? How would she even go to school? Have friends? What would she say to any of them about her upbringing? How long could this charade really last without some serious brainwashing of Amanda to keep it all nice and quiet? A “happy” ending for this story seemed implausible to me even in 2007, which is perhaps why the film doesn’t dwell on it – in 2017, when mass surveillance is a known quantity, and even children’s toys are spying on them, it’s hard to imagine a film even attempting that version. The audience simply wouldn’t accept it. Unless Doyle means the child harm, he simply couldn’t keep her a secret forever. If I were in Patrick’s place, I think I’d have a hard time living with either outcome, especially if Helene continues her reliable track record of being a terrible mother – but at least in this version, he can stop by every once in a while, call Amanda by her real name, and let her know that someone cares about her. And perhaps that’s enough.

FilmWonk rating: 8 out of 10