Despite its title, How to Let Go of the World and Love All the Things Climate Can’t Change, an upcoming HBO documentary from Gasland director Josh Fox, is not trying to convince anyone of the realities of human-caused climate change. Nonetheless, it spends the first 40 minutes of its runtime dwelling on each of those effects in a gonzo, rapid-fire fashion, and allowing Fox, its frequent on-screen subject, to lapse into despair as he gradually learns the enormity of it all. Fox’s emotional journey is fundamentally at the center of the film, and between its frequent reliance on poetic (and occasionally stilted) voiceover to its various montages of original music produced on-screen by people who have been directly affected by climate change, How to Let Go of the World functions less like a documentary, and more like a sort of group therapy session for people who aren’t afraid to accept the scientific consensus and innumerable lines of evidence supporting climate change, but feel ill-equipped to confront that reality in any meaningful way by themselves. Full disclosure: I’m definitely a part of this demographic.

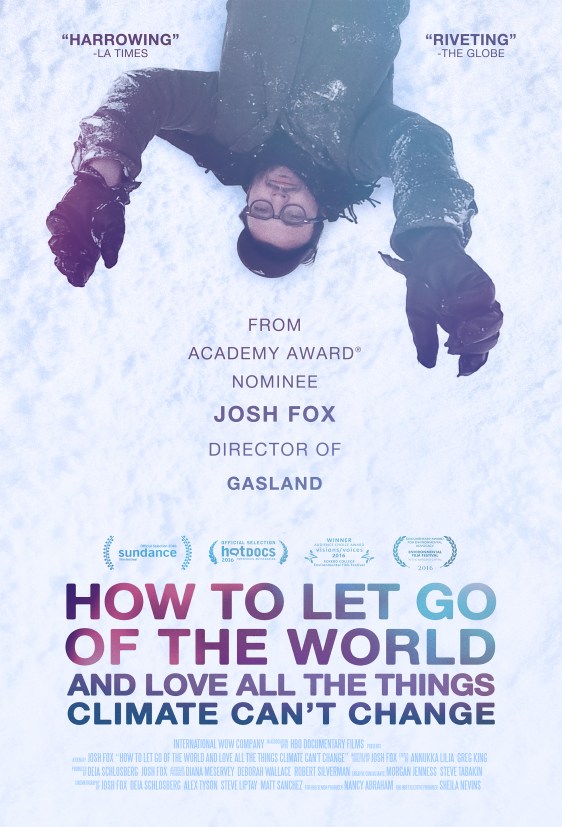

This is an exercise that runs a serious risk of self-indulgence, but what ultimately makes this film work so well is Fox’s credibly humble approach to such a daunting problem as climate change, and beautiful visual storytelling style as he documents this personal journey. He visits the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in New York, witnessing the destruction and death along the Long Island Coast. Even as he remains on camera and speaking over the footage, he removes the focus from himself and points his camera squarely at the poorest and most vulnerable people – a focus that persists throughout the film. As a subway musician begins playing a hauntingly beautiful song (listen to it here!), a montage of Sandy’s unrelenting destruction flows across the screen. What follows is a litany of interviews with various climate experts (including one shot unauthorized in the Ronald Reagan Building cafeteria in D.C.), outlining just how dire the situation is now (with 1C of warming), soon (with a guaranteed 0.5C of additional warming even if we halted all CO2 emissions), and in the future (with a >2C increase). The 5-9 meter sea level rises, the loss of species and ecosystems, the displacement of hundreds of millions of climate refugees, the disease, blight, and death. And then it stops, because it’s all too much. Fox gives up, returns to his Pennsylvania hometown, and collapses into a desperate snow-angel figure on the wintry ground of his favorite childhood forest. The camera floats straight up into the sky as the poetic voiceover continues, shrinking Fox’s person – and potential impact – into a minor black dot in the distant snow. Remember what I said about self-indulgence? This was a genuinely touching moment, and simultaneously the point where if Fox had continued wallowing in his impending doom, I would’ve had a difficult time continuing to take the film seriously. But this is exactly when the film’s journey begins.

Fox asks a new question: What are the things that climate change can’t destroy? What will it leave behind? And in a moment, all of the footage of forests and oceans and glaciers and mountaintops spontaneously gets more lush and beautiful than the bleak, desaturated despair of the first act, and the film becomes nearly as slick a globe-trotting climate change doc as Racing Extinction, while perhaps remaining a bit more grounded in the human storytelling. If we can’t stop the worst effects of climate change, he asks, what can we do? The film hops around the world, telling tales of various local efforts to resist expanded fossil fuel speculation and fight climate change in critical areas. Fox keeps his camera trained on indigenous peoples who are being subjected against their will to the quasi-colonialist expansion of western energy production, posing a question which shouldn’t require an answer in 2016 – should a remote tribe be permitted to live as they wish, even if there is an alternative way of living that our western experience says must be better? We have our cars and lights and antibiotics, but what if these tribes simply have no interest in them?

The film is hardly fetishizing an archetype of the noble savage here – this perspective does not go unexamined as the film goes on. But the film’s initial view of this conflict, between the Ecuadorian government (who had an impending deal with an Argentine oil company) and natives in a remote river village called Sarayaku, presents it as a straightforward moral issue. The natives aren’t merely being offered an alternative to their indigenous lifestyle- they are having the very production of that alternative forced upon them. They can come join us in the cities and play with our plastic widgets and electricity, but we’ll have to destroy their ancestral homeland and drill for oil to create those things. The question of whether one way of life is better or worse than another is a complex one, fraught with questions about human rights and resource allocation and cultural identity. But by focusing on such a specific instance where the rights of the natives were being set aside in a zero-sum manner for those of a fossil fuel company, Fox successfully strips a great deal of the moral complexity out of the situation. Sure, energy production is an essential part of civilization. It warms and empowers and educates people, and can bring them out of poverty. Later in the film, we even see an instance of solar-powered irrigation pumps being distributed in Zambia to help impoverished women make a living by growing and selling vegetables, and thus avoid being swept up into their only alternative trade – prostitution. The film isn’t afraid to muddy the waters a bit on these issues, but it distills them into a fine argument for the idea that people should be free to refuse an outsider’s definition of progress if they wish, especially if it accompanies destruction of their way of life. This is just one small conflict in one small place, but its relevance to the lopsided struggle against climate change is palpable.

This theme continues as the film shifts its focus to Pacific Islanders, whose homes aren’t merely threatened with oil production, but rather total destruction through sea level rise. One unexpectedly poignant section focuses an affable, dancing Samoan man, Mika Maiava (whom Fox ably identifies as “the Jack Black of climate change”), a spokesman for a group of activists called the Pacific Climate Warriors. We first see the Warriors during an impressive segment in which islanders in hand-carved canoes blockade an Australian coal port. This sequence is spectacular in its tense, on-the-water coverage, and I don’t dare speak of it in too much detail. After the blockade is over, as Fox returns with Maiava to his home island to get footage of an odd local custom.

We quickly meet Maiava’s pregnant (and past-due) wife, and he tells the tale: when a baby is born, they save the placenta, and plant it in the ground, along with a coconut tree. The tree grows tall, and forms a life-long connection between the islanders and their homeland as they grow up. I must confess, I initially rolled my eyes a bit at this on-the-nose metaphor, and even wrote in my notes, “Probably don’t need to mention the placenta-trees.” As Maiava and Fox take a roadtrip to visit his father’s tree, the islander engages in what seems to be commonplace gallows humor, joking about how they’re all gonna drown when the island disappears into the sea. And then, with some difficulty, they find the spot. And Mika Maiava transforms in front of me and breaks my heart, as he realizes, for the first time on camera, that his father’s tree is gone. The entire small section of coast where it had been planted had succumbed to coastal erosion. This warrior, who fights every day for the future of his unborn child, is deconstructed before my eyes. His tough, but jovial demeanor melts away, and he is reduced to tears.

This segment embodies what makes this film so effective – its reliance on moments of genuine and irrepressible humanity. I’ve only mentioned a handful of the innumerable segments – Fox also visits the choking smog of Beijing and the Chinese countryside (where the film takes a surprisingly intense turn), melting glaciers in Iceland, and various other locations that climate change is likely to touch in some way. And in each spot, he rapidly establishes a setting and manages to tell a quick, human story in the process. Not all of these vignettes succeed (the “dancing democracy” scene is a bit baffling), but I’m hard-pressed to find one that didn’t affect me in some way. Early in the film, as Fox explores the wreckage of Sandy, he admits a minor journalistic failing, as they walk past the house of a widower whose wife had just drowned in the storm. “I just couldn’t bring myself to point the camera in a grieving man’s face and ask, ‘Can I get your story on camera?'” By bringing his camera around the world and pointing it in the faces of people who are certainly in need of help, but are nonetheless fighting for their futures every day, Fox attempts to flip the script on climate change from a daunting problem that we’re all powerless to arrest, to a daunting problem that we’re empowered to unite and face together. How to Let Go of the World is at once inspiring and sad – and a cultural document that will age in a manner entirely dependent on what we do next.

FilmWonk rating: 7.5 out of 10

How To Let Go of the World premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and is currently on a tour of the US. It will be playing in Seattle from May 20-26 at the Varsity Theatre, and there will be a Q&A with the filmmakers after the Friday, May 20th screening at 7PM. More info at this link. The documentary will also air on HBO this summer.

Editor’s note:

This review seems like a good spot to mention that my home state of Washington is trying to pass a ballot initiative for a statewide, revenue-neutral tax on carbon emissions in November. Pollution gets taxed, and 100% of the revenue goes back to the people. Pretty much a no-brainer economically – we nudge ourselves in the right direction, away from pollution, in a cost-effective manner. If you’re a Washingtonian, know that we have a chance to lead the nation in fighting climate change here and now.

Join the fight today and help I-732 pass in November.