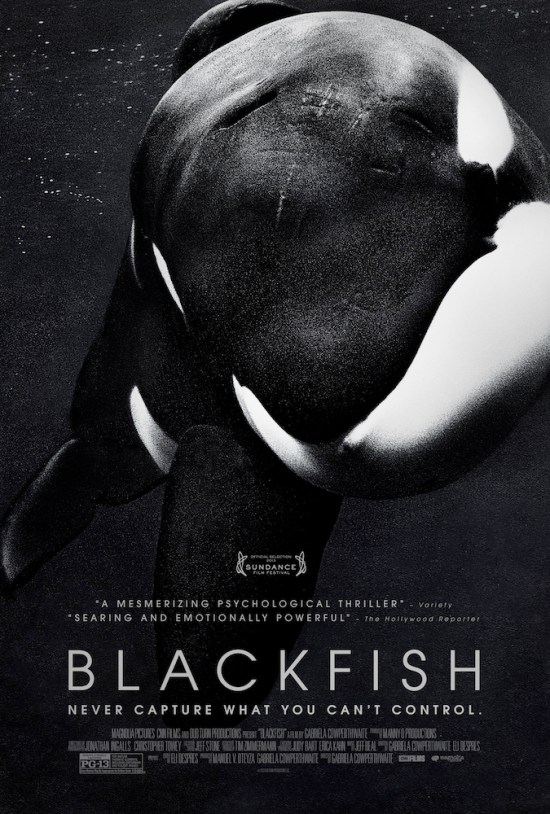

“I can’t imagine a society that values marine mammals as we do…without parks like SeaWorld.”

This quote, from an interview with a former SeaWorld trainer, appears in the latter half of Blackfish, and it is to the documentary’s credit that it doesn’t belabor or even call attention to the bitter irony that this one line so perfectly encapsulates. The film is ostensibly a hit piece on SeaWorld, centering around a captive orca named Tilikum who killed an experienced trainer named Dawn Brancheau in 2010, increasing his career body count to three. It expands upon the company’s allegedly dubious safety record when it comes to protecting those under its purview – animals and trainers alike. The film does moralize about the ethics of keeping captive intelligent animals in a glorified circus, but these moments are few and far between compared to the film’s pragmatism about keeping and interacting with orcas safely.

The film’s central argument seems to be this: If killer whales are potentially lethal, as their moniker would seem to imply, and if they are used to miles of unobstructed ocean territory in which to roam and settle their disputes, they cannot be practically held in captivity with any measure of safety. The moral implications of this point are broached throughout the film, but with an impressive level of subtlety. As a whole, the film is stridently opposed to the practice of keeping captive orcas, but it never feels like it’s making that argument directly. It simply presents the circumstances surrounding SeaWorld’s business and show-biz glamorization of their beloved Shamu(s), and leaves the audience members to reach this conclusion on their own.

The myriad former SeaWorld trainers in the film could come off quite negatively, but they really never feel like perpetrators so much as victims of their own affections and former naïveté. They readily admit that they swallowed and parroted the company line without question, sometimes quite disturbingly (such as when they told parkgoers the laughably false line that orcas live longer in captivity). By and large, the film strikes an effective balance in its tone. If writer/director Gabriela Cowperthwaite had set out to make a film that was morally opposed to keeping captive orcas, she might attract a small audience of like-minded folks who would scream their agreement and continue their previous practice of not going to SeaWorld. This was the problem with 2009’s The Cove, and one of the reasons it had little effect on the Taiji dolphin slaughter (which, as of this writing, continues every spring). It was a film for like-minded people – those who saw no reason for the wanton abuse of marine mammals they saw before them, but could see no means of halting it. While Blackfish might not be a “message film” per se, it is couched in a message of practicality, and guaranteed a wide distribution (the film will be showing on CNN later this year). What’s more, the film’s call-to-action couldn’t possibly be more simple: Don’t go to SeaWorld. Don’t spend your money. As messages go, at least it’s practical.

FilmWonk rating: 8 out of 10

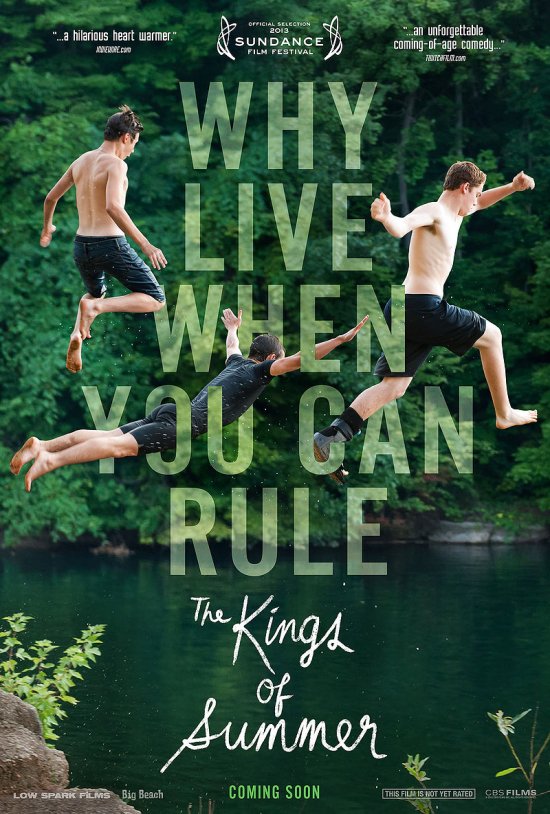

If Wes Anderson‘s Moonrise Kingdom took place in the real world, and were populated with real people, it might look something like The Kings of Summer. The film focuses on a trio of boys who decide to run away and build a makeshift cabin in the woods. Joe Toy (Nick Robinson) seeks to escape the drudgery of playing Monopoly with his surly widower father (Nick Offerman), while his best friend Patrick (Gabriel Basso) just can’t stand his own parents’ (Megan Mullaly and Mark Evan Jackson) enthusiastic and merciless mockery of him- a condition that somehow results in breakouts of actual hives. Also along for the ride is an extraordinarily weird kid, Biaggio (Moises Arias), who might just be the film’s strongest comic performer even if not all of his bizarre non sequiturs land perfectly.

This film would minimally have been a satisfying comedy buffet, with a cast that includes all of the above, along with a fantastic array of supporting performers such as Alison Brie, Mary Lynn Rajskub, and Kumail Nanjiani – but it managed to be something substantially more impressive- a taut, mostly well-drawn tale of teen friendship and rebellion.

The boys indulge in the kinds of backwoods shenanigans that seem, for lack of a better word, utterly real. A boy in the woods, even when he’s playing at becoming a man, will run, jump, climb, swing, chop, pile up, push over, set aflame, and dive into every last rock, tree, or watery delight that the woods have to offer; snakes and mosquitos be damned. In one of the film’s most amusing scenes (which also plays over the opening credits) the boys come across a long drain pipeline and proceed to bang out an impressive rhythm on it with branches. And why? Not because the camera was floating majestically around them, or because the film was desperately seeking some metaphorical catharsis – but because banging on a pipe is fun. For now. And when it stops being fun, we’ll go do something else.

The film depicts some relationships quite strongly while neglecting others. Much of the father-son dynamic is left for the viewer to guess at due to the fairly limited screentime between father and son, but Offerman brings the same stolid hilarity (and occasional vulnerability) that he renders so reliably each week on Parks and Recreation. While the precise source of Robinson’s angst remains a complex mystery throughout the film (despite several proximate causes to choose from), the film manages to draw some credible parallels between father and son. To put it bluntly, they both have the capacity to be miserable, life-sucking bastards. While Offerman’s performance is strong, it is Robinson who manages to impress, proving the rare teenage (or maybe 20-something) actor who can pull off a complex, occasionally solitary lead performance.

Perhaps the film’s biggest weakness is teen love interest Kelly, who feels underwritten despite a passable performance by Erin Moriarty. While she succeeds as a source of conflict between the two friends, we glean very little of what she really wants out of the situation, and the character seems to have precious little agency of her own. Nonetheless, the conflict does feel credible, particularly in its resolution – or rather the light tapering in hostilities that feels far more true-to-life than some dramatic, emotional exchange would have been. These are teenage boys. A sentimental exchange of middle fingers is really the closest thing to a tearful hug that we can hope for.

FilmWonk rating: 7 out of 10