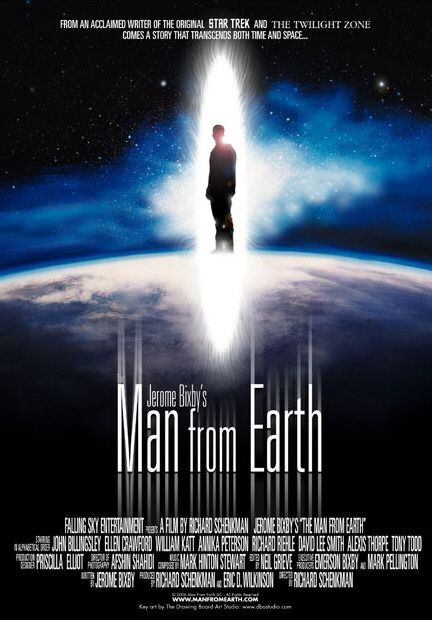

Produced in 2007 from a screenplay finished on the writer’s deathbed, Jerome Bixby’s sci-fi opus The Man From Earth feels more like a play than a film. Professor John Oldman (David Lee Smith) announces to his colleagues and friends that he’ll be moving on, but makes a surprise confession – he is immortal, and has lived for the past 14,000 years. The rest of the film takes place almost entirely in a single room, following the threads of the group’s conversation. And in a very theatrical touch, the assembled group of academics are perfectly suited to test his story. There’s Harry – a biologist (John Billingsley), Dan – an anthropologist (Tony Todd), Sandy – a historian (Annika Peterson), Art – an archaeologist (William Katt), and Edith (Ellen Crawford), a devout Christian with an unnamed specialty. As John’s story goes on, they are joined (quite expectedly) by Dr. Will Gruber (Richard Riehle), a psychologist.

I mention the character names, but these aren’t really characters anyway. They’re just filters through which the audience can analyze this man’s fantastical tale. There is even a student (Alexis Thorpe) present to ask a few simplistic questions so the professors can explain details that the group would already know. And even when the story strives for more dramatic and theatrical character moments (a confession of love, a surprise death threat, and so on), the situation never quite feels plausible, as these moments only serve to provoke new dimensions to John’s story.

But as I mention these character and narrative shortcomings, I must also say this – not a single one of them detracts from the film. David Lee Smith gives a remarkably subdued performance as John Oldman (one of many pun names he claims to have chosen over the years), the wise, humble, and pragmatic old soul. He reminded me somewhat of Doctor Who, but he feels far more authentic and human, because the film so excels at depicting the limitations of his purportedly vast knowledge and experience.

As they quiz him for every detail of the last 14,000 years, he points out that he doesn’t remember every detail any more than we can remember every moment of our childhoods. As he produces details of history, anthropology, and social and scientific advancement, they rightfully point out that he could have gleaned any of them from a textbook. But as one professor admits, it is no more possible for John to prove his story than it is for any of them to disprove it. And so the conversation goes on. He talks of love, friendship, life, and death – the one subject of which he has no more knowledge than anyone else. The film goes on to raise some startling religious themes, to the chagrin of Edith, the devout Christian… The ensuing theological discussion is easily the most provocative aspect of this film, and is quite well realized.

I don’t have much to say about the other performances, since there weren’t any other particularly strong characters. But even as a collection of variable filters for John’s conversation, the acting was solid overall. Todd, Crawford, and Riehle were superb, and Billingsley was enjoyable, albeit playing to familiar quirky territory. Annika Peterson does the best she can with some of the more contrived character moments, although her unlikely conversation with John about the nature of love is a surprisingly effective addition to the film. Katt and Thorpe don’t contribute much as skeptic and simpleton respectively, but I don’t really fault their performances, as they aren’t given much to do in the film (except make the audience wonder why a fifty-something doppelganger of James Cameron is permitted to date one of his students).

Jerome Bixby was a writer for the original “Star Trek” series, and it definitely shows here. The film’s end features Tony Todd announcing he’ll go home and “watch some ‘Star Trek’ for a little sanity”, and while it was a mildly self-indulgent reference, it does bring to mind a key difference between the two works. “Star Trek”, with its niche audience, was quite free to explore the big sci-fi ideas via alien allegory, since no one was too worried about offending the delicate sensibilities of the Tholian Empire. The Man From Earth takes on a far more daunting task – to deconstruct human history, values, and beliefs in a manner as shocking as it is insightful, and keep the audience adequately engaged to stop them squirming in their seats and fleeing the room. And it completely succeeds.

FilmWonk rating: 8 out of 10